2024 Public Health Laboratory Annual Report

Lab Scientists Boosted by New Job Classification

In government, job classifications can make a big difference to employees. Before a recent change, many scientists of the Minnesota Department of Health’s (MDH) Public Health Laboratory (PHL) and Minnesota Department of Agriculture (MDA) had job titles and job descriptions that bore little resemblance to the work they did every day. Their pay also did not reflect the level of expertise their jobs required.

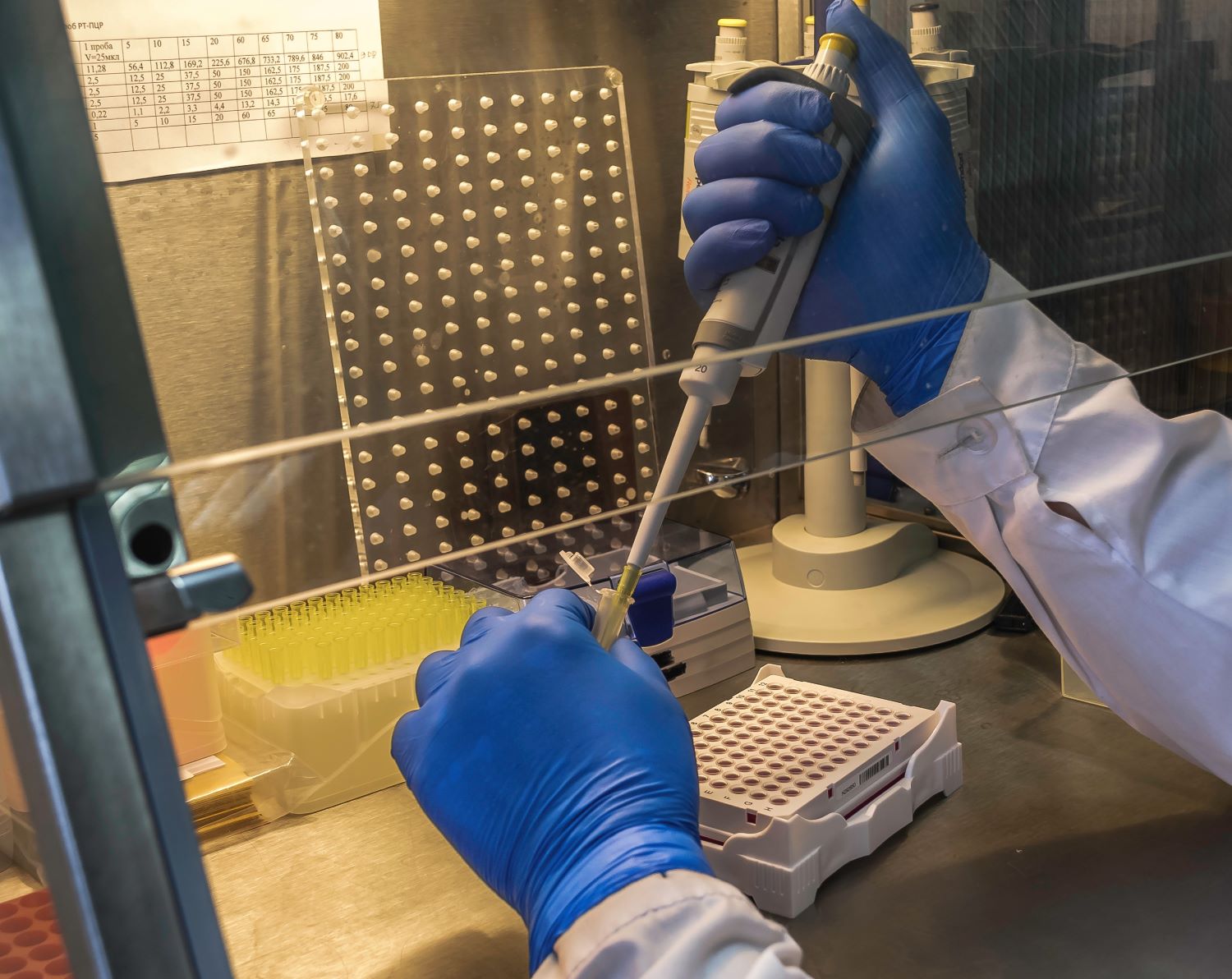

A majority of PHL employees run tests on samples sent by outside sources. Lab scientists test drinking water, blood, soil, stool samples, and more. Their tests may confirm the presence of an infectious disease, identify environmental contaminants, or be the key to finding out if a newborn has an inherited genetic disorder. Hundreds of samples are processed every day.

A majority of PHL employees run tests on samples sent by outside sources. Lab scientists test drinking water, blood, soil, stool samples, and more. Their tests may confirm the presence of an infectious disease, identify environmental contaminants, or be the key to finding out if a newborn has an inherited genetic disorder. Hundreds of samples are processed every day.

It is complex and highly specialized work, and there is little room for error. Mistakes could introduce impurities into samples that would invalidate dozens of test results. Testing schedules are strictly mandated by law because samples are only useable for brief periods of time.

Testing Has Changed

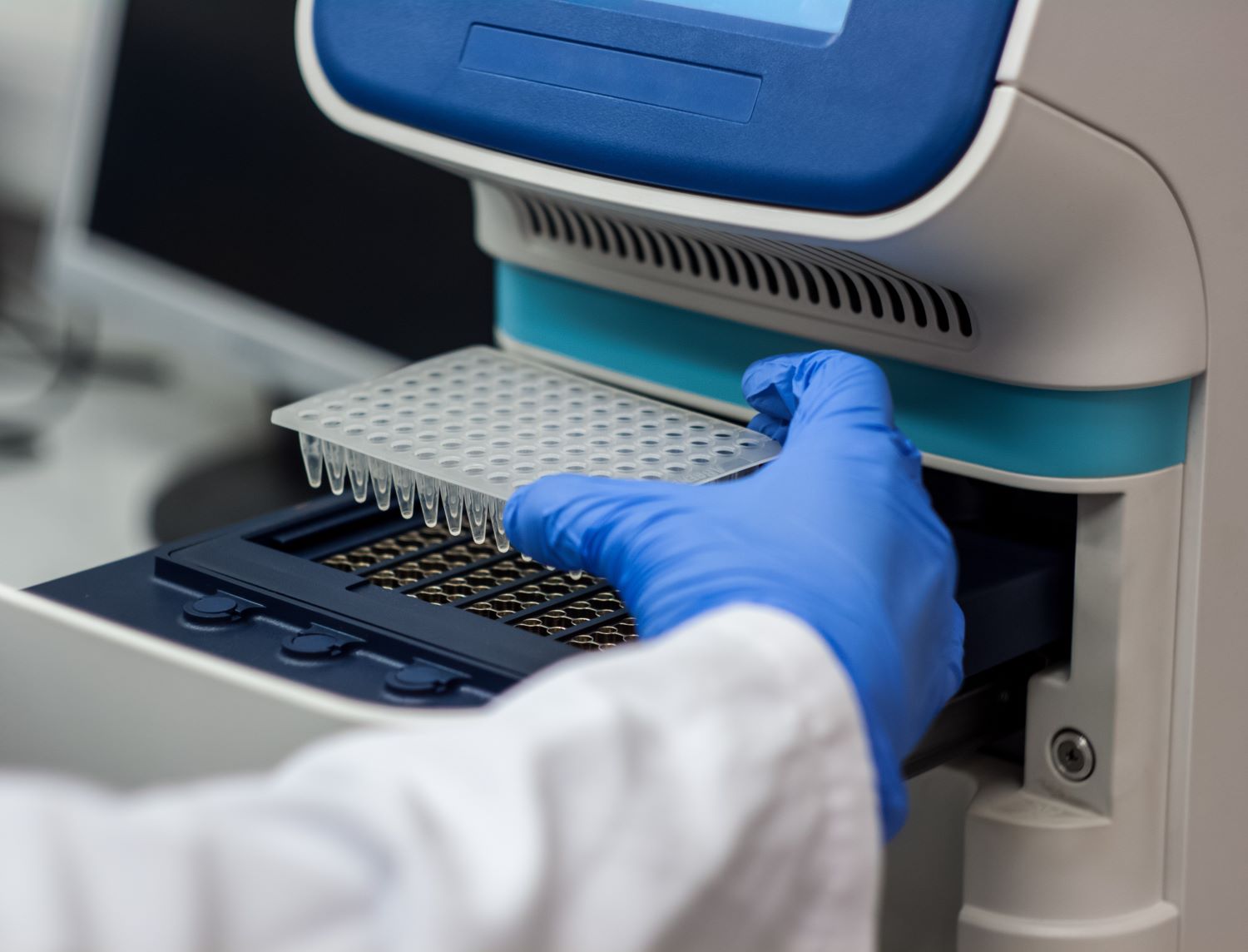

The nature of testing has changed dramatically over the years. Technological advances have greatly expanded what can be tested for and how effective tests can be. Operating the sophisticated machinery requires extensive training and skill.

Until recently, many lab scientists were classified as bacteriologists or environmental analysts. These job classifications were created more than 35 years ago to encompass very different jobs. They specified long-outdated techniques and technology. Newborn Screening Program employees who held the job titles of environmental analysts actually investigated newborns’ blood samples to detect inherited and congenital conditions. Many so-called “bacteriologists” did not work with bacteria at all.

Until recently, many lab scientists were classified as bacteriologists or environmental analysts. These job classifications were created more than 35 years ago to encompass very different jobs. They specified long-outdated techniques and technology. Newborn Screening Program employees who held the job titles of environmental analysts actually investigated newborns’ blood samples to detect inherited and congenital conditions. Many so-called “bacteriologists” did not work with bacteria at all.

Also, the compensation proscribed by the bacteriologist and environmental analyst job classifications was significantly below that of private-sector scientists doing the same difficulty of work. Retaining employees had proven difficult.

A New Approach

To fix this problem, then-Division Director Myra Kunas of the PHL (now an Assistant Commissioner at MDH) and then-Assistant Division Director Sara Vetter of the PHL (now Division Director of the PHL) started creating the Laboratory Scientist Classification Series. Supervisors from MDA and the PHL worked together to survey scientists and create benchmarks for the new job descriptions.

Creating a new job classification is no easy task. The PHL and MDA had to work with a contractor to determine if the proposal was appropriate. Then both made their recommendations to Minnesota Management and Budget and Human Resources.

Thanks to the collective work of these agencies, the Laboratory Scientist Classification Series was born. It creates the position of laboratory scientist levels 1, 2, and 3. The job starts at a higher salary, which increases at each level.

| “It is finally nice to be called a scientist!” said Sarah Bistodeau (pictured, right), laboratory scientist 3. “’Bacteriologist’ was just so wrong; as a virologist, I didn’t even work with bacteria.” |  |

Critically, the job description for laboratory scientist reflects abilities and skills instead of being tied to certain techniques or technologies. The position thus has the flexibility to adapt to changing methods and unforeseen challenges.

The backbones of both the PHL and MDA are formed by the newly minted laboratory scientists, along with the research scientists, who do more research and development and less day-to-day testing. With a strong, stable set of laboratory and research Scientists, both the PHL and MDA can continue their exemplary work protecting Minnesotans and meeting any unpredictable new threats.

Return to the main 2024 Annual Report page.