Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS)

About Us

Information

Contact Info

High Blood Pressure (hypertension during pregnancy)

PRAMS question of the quarter

Which of the following is NOT a potential complication of preeclampsia?

- Placental abruption

- Fetal macrosomia

- Hemolysis Elevated Liver Enzymes Low Platelet Count (HELLP) syndrome

- Eclampsia

Find the answer at the bottom of this webpage.

High blood pressure (hypertension during pregnancy)

A focus on U.S. born Black/African American women in Minnesota

This feature covers hypertension during pregnancy and includes prevalence, definition, symptoms, prenatal care, birth outcomes, management, as well as recommendations and resources for improving health outcomes.

Prevalence

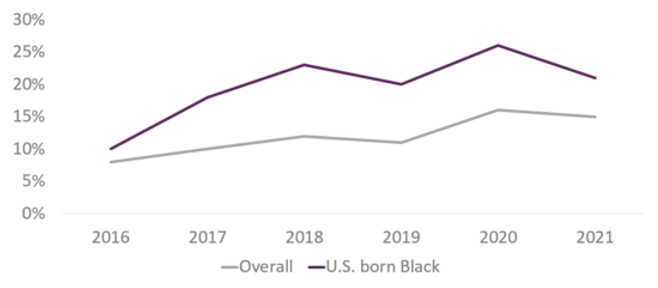

The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rates among developed nations, with maternal morbidity doubling over the past decade and maternal mortality rising 61% in the last three years alone. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (HDPs) including pregnancy-associated hypertension are the leading causes of pregnancy-related death in the United States.1 The MN PRAMS data presented in Figure 1 illustrates self-reported hypertension among birthing people in Minnesota and sheds light on this prevalent issue within the state.

Figure 1- Self-reported hypertension during pregnancy in Minnesota, 2016-2021

Definition

Blood pressure is the pressure of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries. It is measured as two numbers. The top number is the pressure against the artery walls when the heart contracts (systolic), and the bottom number is the pressure against the artery walls when the heart relaxes (diastolic). Although there are different types of hypertensions during pregnancy, this newsletter focuses on hypertension identified during pregnancy. Hypertension during pregnancy is diagnosed when a person has persistently high blood pressure readings (specifically when the systolic is greater than 140, or the diastolic is greater than 90, or both) on two separate occasions, at least four hours apart, after 20 weeks of pregnancy, and in the absence of any previous diagnosis of hypertension. There are usually no symptoms with hypertension. 2,3

During a pregnancy, it is possible to develop pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, or both. Pre-eclampsia usually happens after 20 weeks but can develop earlier in some cases. It can also occur in the weeks after pregnancy. Preeclampsia is a serious blood pressure disorder and is characterized by high blood pressure and signs of damage to organs in the body. If pre-eclampsia is untreated or undertreated, it can lead to a life-threatening complication called eclampsia, which is new onset of seizures.2

If left untreated, hypertension during pregnancy can lead to many complications for birthing people and their baby, some of which include having a baby with low birthweight, delivering a baby before 37 weeks, longer hospital stays, seizures, stroke, coma, or death.

Signs and symptoms of preeclampsia

Pregnant people with preeclampsia may experience symptoms such as a severe headache that will not go away, swelling of face, hands, or legs, sudden weight gain, difficulty breathing, seeing spots or vision changes, pain in the upper abdomen or shoulder, or nausea and vomiting.4

Below is a quote from a mom sharing her story about the importance of knowing what to look for:

"I was pregnant with twins and was very educated on the signs of pre-eclampsia. This was good because I only had one symptom (puffy legs, hands, face) and asked my health care provider to check my blood pressure. It turned out that I did have pre-eclampsia and I brought it to their attention." ~ MN PRAMS survey respondent

Structural Racism

Before discussing risk factors, care during pregnancy, and birth outcomes among U.S. born Black women, it is important to note that structural racism is a root cause of social determinants of health and leads to racial health disparities. MN PRAMS data is used below to show some of these disparities.

Risk factors

Some people have a higher risk of developing hypertension during pregnancy. Some risk factors can include age, weight status, hypertension in a previous pregnancy, having chronic (long term) high blood pressure, Type I or II diabetes, gestational diabetes, or family history of hypertension.

Combined PRAMS data from 2016-2021 identified that 19% of women with gestational diabetes also had high blood pressure during pregnancy compared to 11% without gestational diabetes. Among U.S. born Black women, 40% who self-reported gestational diabetes also reported hypertension during pregnancy compared to 18% who did not self-report gestational diabetes. Among white women, 19% who self-reported gestational diabetes also reported hypertension during pregnancy compared to 12% who did not self-report gestational diabetes.

In terms of weight status, the percentage of women who were obese (Body Mass Index (BMI) >= 30 kg/m2) and self-reported hypertension during pregnancy was over twice that of women who were not obese (21% vs 9% respectively). Among U.S. born Black women, 25% were obese (BMI >= 30 kg/m2) and self-reported hypertension during pregnancy compared to 17% who were not obese. Among white women, 22% were obese (BMI >= 30 kg/m2) and self-reported hypertension during pregnancy compared to 9% who were not obese.

Care during pregnancy

In Figure 2 below, MN PRAMS combined data from 2016-2021 showed disproportionate percentages of self-reported hypertension during pregnancy over time among U.S. born Black women compared to all women in Minnesota. These existing racial disparities were also exacerbated in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, where 26% of U.S. born Black women self-reported hypertension during pregnancy compared to 16% of all women in Minnesota. Although the percentages of self-reported hypertension during pregnancy appear to have declined overall and for U.S. born Black women in 2021, the wide gap in disparities between U.S. born Black women and all women in Minnesota still exists.

Figure 2- Self-reported hypertension during pregnancy over time, 2016-2021

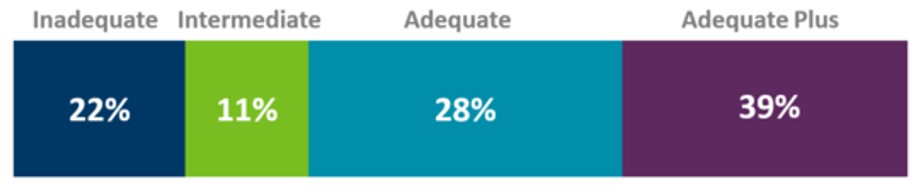

Early and adequate care is essential for optimal health throughout pregnancy and delivery, particularly for those with hypertension. The Kotelchuck index measures whether pregnant people had adequate prenatal care based on the number and frequency of prenatal visits. Inadequate prenatal care begins after the fourth month of pregnancy or includes less than 50% of the recommended number of visits. Intermediate, adequate, and adequate plus care begin in the first four months of pregnancy but intermediate care also occurs with 50-79% of the recommended number of visits, adequate care also occurs with 80-109% of the recommended number of visits, and adequate plus also occurs with 110% or more of the expected prenatal care visits. 5,6 Combined MN PRAMS data from 2016-2021 showed that overall, 80% of women reporting hypertension during pregnancy and those not reporting hypertension during pregnancy said they had at least adequate care (includes adequate and adequate plus responses). Figure 3 shows that among U.S. born Black women, the percentage who self-reported hypertension during pregnancy and said they received at least adequate care was 67% and 33% said they had less than adequate care (includes inadequate and intermediate responses). However, among white women, the percentage who self-reported hypertension during pregnancy and said they received at least adequate care was 85% and only 15% said they had less than adequate care.

Figure 3- Adequacy of prenatal care among U.S. born Black/African American women, 2016-2021

The data identified structural or financial challenges that were prevalent within the healthcare system. Of U.S. born Black women who reported they did not enter into prenatal care as early as they wanted, 22% reported that they could not get an appointment when they requested one. Moreover, a higher percentage (33%) of women who were covered by Medicaid for their prenatal care reported that they couldn’t get an appointment when they requested one, compared to 28% of women who were not covered by Medicaid. These longer wait times for appointments may be due to delays in finding a healthcare provider who will accept Medicaid patients. Many healthcare providers are unwilling to accept Medicaid patients because of lower reimbursement rates for Medicaid compared to private insurance. Additionally, Medicaid patients may experience delays in scheduling appointments due to delays associated with gaining coverage. 7 Furthermore, 15% reported the doctor or their health plan would not start care as early as requested, 18% reported they did not have enough money or insurance to pay for their visits, 18% reported they didn't have their Medicaid, Medical Assistance, or MNCare card, and 14% reported they did not have any transportation to get to the clinic or doctor's office. These healthcare and insurance system challenges often intersect with concerns that health care providers do not listen to women’s concerns. Here is one woman’s story:

"I had very high indications of preeclampsia and wasn’t taken seriously until it was almost too late. I had really bad pain and couldn’t breathe before my child was born. My feet and legs were so swollen I went up 2-3 shoe sizes, had high blood pressure, and saw spots while I was pregnant. They kept putting off what I was saying. I went to the ER for my pain thinking it was gas/constipation and it was found my liver enzymes were extremely high (500+). I had to have an emergency C-Section. I ended up staying in the hospital for 4 days until my enzymes were tolerable and had to take blood pressure pills days after I came home. Providers need to listen and pay attention to their patients. I’m now 3 months postpartum and still having liver issues. My hair has been falling out in clumps and I wasn’t at all prepared for how much hair I would lose." ~ MN PRAMS survey respondent

Or the challenges intersect with racial bias and discrimination, compounding disparities in care and worsening health outcomes. Analysis of 2016-2021 MN PRAMS data showed that almost one in 10 U.S. born Black women reported they experienced discrimination by healthcare providers during their prenatal care, labor, or delivery based on their race, ethnicity, or culture. Here’s another story shared by a PRAMS respondent:

"I would like to touch base on preeclampsia and how important it is to advocate for yourself and ask to be checked. I didn't get the care I needed, and I almost lost my life. It's important to be aware of preeclampsia and the effects it can have. I think there should be more education about it. Also, listen more to African Americans and minorities. It tends to get brushed under the rug when we have health issues." ~ MN PRAMS survey respondent

Inadequate access to stable housing is also a determinant of health, particularly for pregnant people who have hypertension. Individuals who experience homelessness experience increased challenges accessing early and adequate care and this can exacerbate health outcomes. The combined MN PRAMS data from 2016-2021 showed that 13% of U.S. born Black women revealed that they were homeless or had to sleep outside in a car, or in a shelter 12 months before the birth of their baby compared to 1% of white women. Also, 26% of U.S. born Black women reported they had problems paying the rent, mortgage, or other bills compared to 11% of white women. Minnesota has a history of discriminatory housing policies including racial covenants and redlining. Research has shown that residents of redlined areas experience a decline in property values and a reduction in their overall quality of life. These adverse living conditions encompass exposure to industrial toxic waste, limited access to grocery stores offering fresh produce, higher crime rates, increased poverty, and a prevalence of health issues.8 In fact, a study looking at the association between historically redlined districts and racial disparities in current obstetric outcomes found that women living in “hazardous” areas based on racially discriminatory criteria, experienced increased odds of maternal complications, such as pregnancy-related hypertension, and neonatal complications, such as low APGAR scores and higher rates of neonatal intensive care unit admission.9

Birth outcomes

Uncontrolled or under controlled hypertension during pregnancy can result in adverse maternal and child health outcomes. Exploring the relationships between hypertension during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes reveals critical insights into maternal and infant health disparities and highlights the need for early detection and treatment.

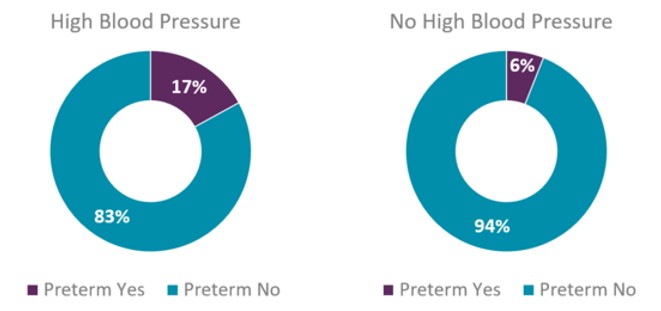

Preterm birth and low birthweight are outcomes of significant concern. The cost associated with preterm birth and low birthweight is staggering. A study looking at 763,566 infants with insurance coverage through Aetna, Inc. for the first six months of post-natal life found that they received approximately $8.4 billion in healthcare services. Infants with billing codes indicating preterm status (<37 weeks) incurred medical expenditures of $76,153 on average, while low-birthweight status (<2500 g) was associated with average spending of $114,437.10

Analysis of MN PRAMS data collected from 2016-2021 showed that 17% of women who self-reported hypertension during pregnancy had a preterm birth (<37 weeks) compared to 6% of women who did not self-report hypertension (Figure 4).

Figure 4- Preterm birth among women with and without hypertension during pregnancy, 2016-2021

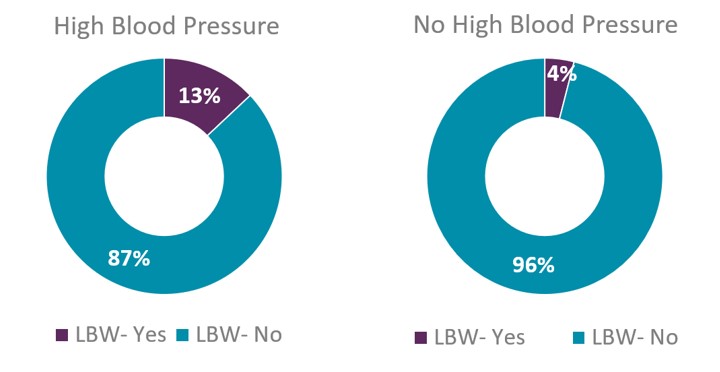

Furthermore, racial disparities persist. Among U.S. born Black women, 24% reported experiencing both high blood pressure during pregnancy and preterm birth, while among white women, 14% reported experiencing both high blood pressure during pregnancy and preterm birth. In Figure 5, the data indicated that the percentage of low birthweight (<2500 g or 5.5 lbs.) babies among women with self-reported hypertension during pregnancy was over three times higher than among those who did not self-report hypertension during pregnancy (13% vs 4% respectively).

Figure 5- Low birthweight among women with and without hypertension during pregnancy, 2016-2021

Among U.S. born Black women, 25% reported they had hypertension during pregnancy and delivered a small baby (<2500 g or 5.5 lbs.) while among white women, 9% self-reported hypertension during pregnancy and delivered a small baby.

Babies who are born prematurely and with low birthweight have longer hospital stays. MN PRAMS analysis of the 2016-2021 combined data showed that 17% of PRAMS respondents self-reported high blood pressure during pregnancy and said that once delivered, their baby stayed in the hospital anywhere from six days to more than 14 days (includes responses to six-14 days, more than 14 days, and still in hospital at time of survey) compared to 5% of women who did not self-report hypertension during pregnancy. When stratified by race, among U.S. born Black women, 25% self-reported hypertension during pregnancy and reported that once delivered, their baby stayed in the hospital anywhere from six days to more than 14 days. However, among white women, 14% self-reported hypertension during pregnancy and once delivered, their baby stayed in the hospital anywhere from six days to more than 14 days. Here is a story of a mother whose experience encompasses all the birth outcomes above:

"This second pregnancy was also healthy, but my son was born six weeks premature. He was healthy but needed to stay in the NICU for two and a half weeks for monitoring and assistance with feeding because he was born at 4 lbs. 7oz. I was diagnosed with hypertension/preeclampsia upon admission to the hospital. The healthcare providers did biopsy my placenta and found chronic chorioamnionitis and a small placental abruption, with no known cause or way to know if it occurred during labor but are both causes of preterm labor and common in people with preeclampsia." ~ MN PRAMS survey respondent

Management

Managing hypertension during pregnancy is important for the health of birthing people and babies. It is important for pregnant people to know the warning signs associated with higher blood pressure, and those with hypertension should ask their doctor about obtaining a blood pressure monitor. Healthcare providers should encourage discussion, education, and tools for individuals to measure their blood pressure and understand abnormal readings. Blood pressure monitors usually come with a free blood pressure management app that allows the user to see their daily, weekly, or monthly measurements immediately and identify trends quickly. Data from the app can also be shared with the medical team for timely intervention. Minnesota has Medicaid coverage of self-measured blood pressure monitoring with a validated device and patient education and training.11 Although the experiences of the two mothers below are from the postpartum period, they still highlight the benefits of home monitoring for early detection and management of hypertension.

"I had post-partum preeclampsia, which developed 4 days after discharge and wasn't caught by a doctor -- I happened to take my blood pressure at home and caught it. During that time, I was in a clinic for a regular check-up for the baby, but I wasn't screened. New birthing parents should have their blood pressure checked at appointments for their babies." ~ MN PRAMS survey respondent

"Had postpartum hypertension. Was checking blood pressure at home after discharge + it spiked 3-4 days postpartum. I was readmitted for two days and treated. I took blood pressure meds until about 5 weeks postpartum. Medical team was very proactive and advised me to check at home since it was borderline too high." ~ MN PRAMS survey respondent

It is also important to maintain a healthy diet rich in fruits and vegetables while limiting sodium intake. Regular physical activity and managing stress can also help to lower blood pressure. Additionally, it is essential for people with hypertension during pregnancy to get care early, attend all prenatal care appointments, and follow the medical teams’ recommendations.

In summary, it is essential to emphasize the importance of early detection, proactive management, and regular prenatal care in reducing the risks associated with hypertension during pregnancy. Integral aspects of this include addressing the factors that exacerbate the risk of hypertension during pregnancy such as removing structural barriers to accessing health care services, listening to expectant mothers' concerns and fostering open communication, while combating the impact of structural racism on maternal health outcomes.

Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: High Blood Pressure During Pregnancy

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG): Preeclampsia and High Blood Pressure During Pregnancy

- National Institute of Health: Pregnancy and High Blood Pressure

- March of Dimes: High Blood Pressure During Pregnancy

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HEAR HER Campaign

- Minnesota Perinatal Quality Collaborative (MNPQC): The Blue Band Project

References

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials: Addressing Hypertension in Pregnancy to Reduce Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG): What’s the Concern About High Blood Pressure During Pregnancy? An Ob-Gyn Explains

- The American Heart Association: Hypertension in Pregnancy: Diagnosis, Blood Pressure Goals, and Pharmacotherapy: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG): Preeclampsia and High Blood Pressure During Pregnancy

- National Vital Statistics Report: Changes in Prenatal Care Utilization: United States, 2019-2021

- American Journal of Public Health: An evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a proposed Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index

- Health Services Research: A systematic review of the qualitative literature on barriers to high-quality prenatal and postpartum care among low-income women

- ArcGIS StoryMaps: Housing Segregation: Redlining in the Twin Cities, Minnesota

- Journal of the American Medical Association: Associations Between Historically Redlined Districts and Racial Disparities in Current Obstetric Outcomes

- Journal of Perinatology: Estimates of healthcare spending for preterm and low-birthweight infants in a commercially insured population: 2008–2016

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials: Addressing Hypertension in Pregnancy to Reduce Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

Answer to PRAMS question of the quarter:

Fetal macrosomia is NOT a complication of preeclampsia.

For more information on the impacts of high blood pressure for everyone, visit MDH’s hypertension webpage or explore the chronic conditions dashboard to learn more about who in Minnesota reports having hypertension.