Center of Excellence in Newcomer Health

- Minnesota Center of Excellence in Newcomer Health Home

- About

- Clinical Guidance and Clinical Decision Tools

- Health Education

- Publications and Presentations

- Trainings

- Newcomer Health Profiles

Spotlight

- Haitian Clinical Guidance

- OB-GYN Care for Afghans: A Toolkit for Clinicians

- Immigrant Health Matters

- Newcomer Education for Wellness Video Series

- MNCOE Connect

Related Topics

Iraqi Refugee Health Profile

Last updated: March 2024

Last updated: March 2024

On this page:

Priority health conditions

Background

Population movements

Health care and conditions in camps and urban settings

Medical screening of U.S.-bound refugees

Health information

Summary

References

Priority health conditions

The health conditions listed below are considered priority health conditions in caring for or assisting Iraqi refugees. These health conditions represent a distinct health burden for the Iraqi refugee population.

Background

Iraq is located in the Middle East bordering Iran, Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait; it has a small seacoast on the Persian Gulf (Figure 1).

As of 2013, the Middle East has the highest number of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) of any region in the world (1). Since the early 1980s, Iraq has faced wars, political instability, and economic sanctions, resulting in the displacement of over 9 million people—approximately 7 million have fled the country, and 2 million are internally displaced (2). The most recent Iraqi displacement began in 2003 with the US-led war in Iraq and the sectarian violence that followed (3).

Over 80% of Iraqi refugees originate from Baghdad (4). Since 2003, Iraqi refugees have settled mostly in Jordan and Syria, but also in smaller numbers in Egypt, Iran, Lebanon, Turkey, and the Gulf States (5).

Figure 1: Map of Middle East

Source: Kevin Liske, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ), CDC

Arabic, the official language of Iraq, is spoken by approximately 77% of Iraqis as a first language. Almost all Iraqis speak Arabic with some level of proficiency (2) (6).

Other languages spoken in Iraq include

- Kurdish – spoken by the Kurds (20% of the population)

- Anatolian Turkish – spoken by the Turkomans (5%-10% of the population)

- Syriac, Neo-Aramaic – spoken by the Assyrians (3%-5% of the population)

- Mandaic and other Neo-Aramaic varieties, Shabaki, Armenian, Roma, and Farsi are each spoken by less than 1% of the population (2).

Prior to the 1991 Gulf War, Iraq had one of the best educational systems in the Middle East, including respected institutions of higher education in science and technology. However, by 2004, only 55% of Iraqis aged 6-24 were enrolled in school (6). Literacy is estimated at 74% for youth aged 15-24 and higher among Iraqis aged 25-34 (4).

Almost half of Iraqi immigrants who participated in the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey were classified as limited English proficient (10). Of Iraqis over age 5 years, 9% reported speaking “English only” and 44% reported speaking English “very well”; 47% reported speaking English less than “very well.” Over half of limited English-proficient Iraqi immigrants spoke Arabic (53%), 29% spoke Syriac/Aramaic/Chaldean, and 11% spoke Kurdish (10).

Islam is practiced by 95% of the population (6); ~63% are Shia and ~32% are Sunni Muslims (11). Minority religious groups include Chaldo-Assyrians, Sabeans, Mandaeans, and Yazidis, about half of whom have fled Iraq due to persecution (11). Although they represented less than 5% of the prewar Iraqi population, 40% of Iraqi refugees registered as Christians, and 62% of Iraqis resettled in the United States by 2008 identified themselves as Christian (11).

The family is the center of life for most Iraqis; it represents honor, loyalty, and reputation, and a person’s social standing is usually determined by his or her family (4). Like most Arab societies, Iraqi society is patriarchal, and men tend to have more decision-making power than women.

Husbands and fathers may accompany their wives and children to medical appointments because the health of each individual is important to the family as a unit (12). Like many refugee groups unaccustomed to the US health care system, Iraqi refugee patients may feel dissatisfied with the quality of care if they do not receive a tangible treatment or prescription medication (12). CDC and state and local health partners learned from focus groups with Iraqis in the United States that many experienced confusion about whether to go to their family physician or the emergency room in case of an emergency (8). Even though most Iraqis are familiar with and respectful of Western medicine, preventive health care may not be a priority; patients are likely to resist physician-driven changes in diet and exercise, regular screenings, and follow-up appointments (13). Discussions with female Iraqi refugees regarding preventive care revealed that disease prevention is seen as a function of hygiene and diet, rather than something achieved through health care providers (14).

For more information about the orientation, resettlement, and adjustment of Iraqi refugees, visit EthnoMed: Iraqi.

Population movements

Calculating the total Iraqi refugee population is difficult because Iraqi refugees are not required to register with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (15). Some refugees avoid registration for fear that they will be detained or deported. In 2006, Jordan had the highest estimated ratio of refugees to total population of any country in the world (16). Due to the current unrest in Syria, Iraqi refugees there are increasingly returning to Iraq (35).

The first waves of Iraqi refugees arriving in Syria and Jordan in 2003 brought resources with them, and they did not need assistance. Most did not register with UNHCR and lived alongside non-refugee Iraqis, urban Jordanians, and Syrians (4) (6). Subsequent waves of Iraqi refugees in Syria and Jordan tend to live with families or rent apartments, often in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions (17).

Table 1: Top Countries of Residence for Iraqi Refugees who Resettled in the United States, 2008-2013 (N=90,607)

Source: CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification system (EDN) (18)

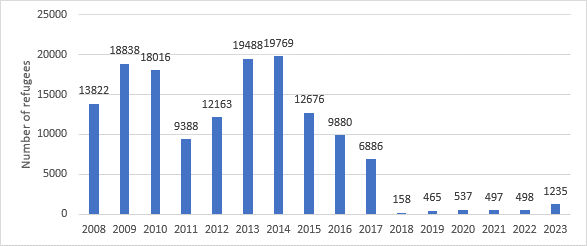

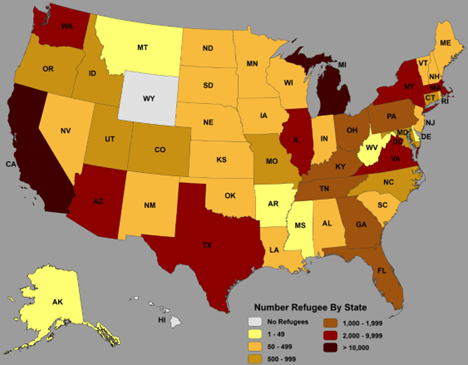

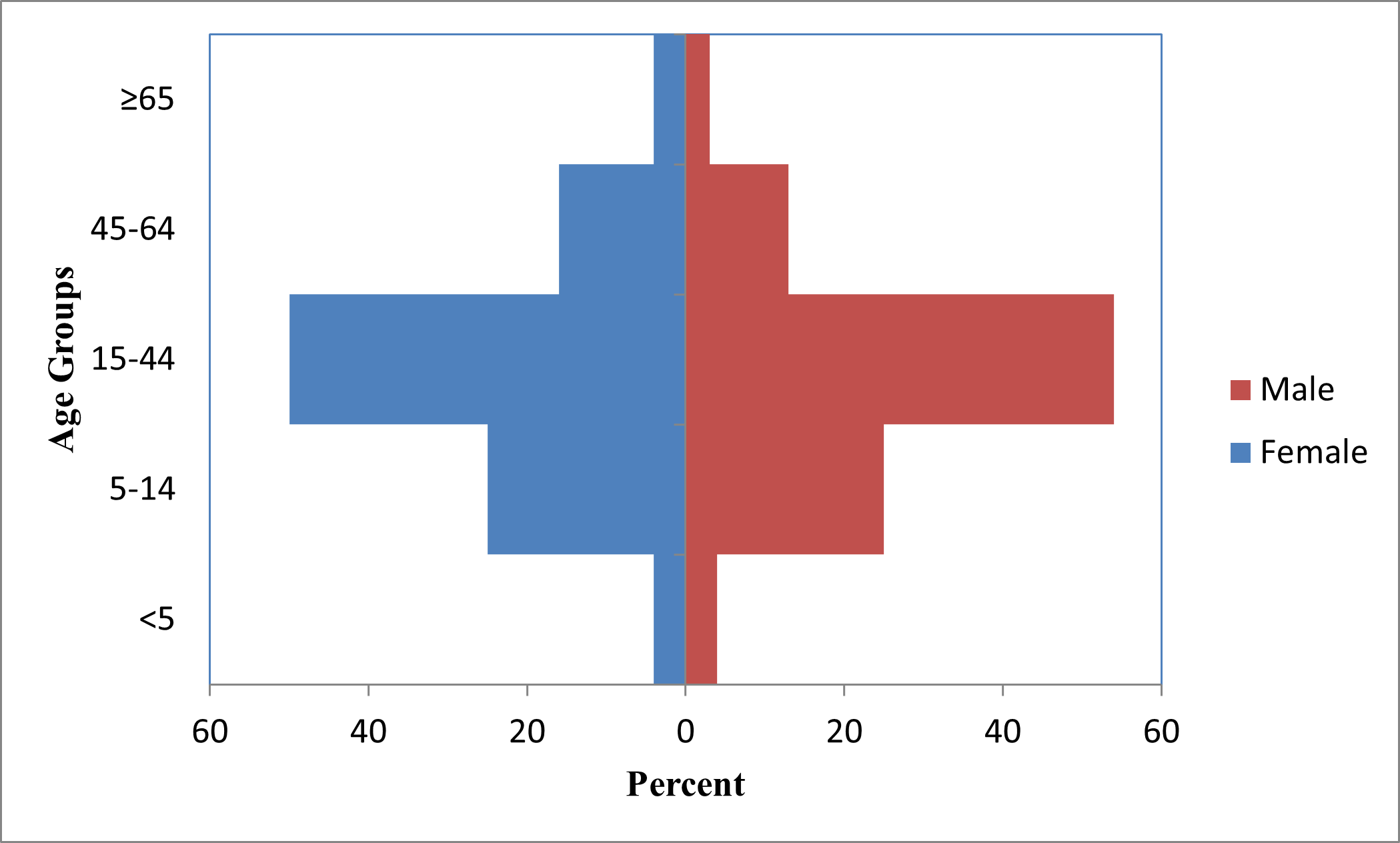

Before Iraqis came to the United States as refugees, many came as immigrants. Detroit, Chicago, and San Diego have the largest Iraqi-American communities in the country (6). Iraqi refugees resettling in the United States in recent years are from a number of countries (Table 1) and they are joining nearly 12,000 Iraqis who were admitted after the first Gulf War (6). Approximately 150,000 Iraqis arrived from 2008 to 2023 (Figure 2). As of 2013, the largest communities are in California, Michigan, Texas, Arizona, and Illinois (Figure 3) (19). However, once refugees arrive in a state as part of the US Resettlement Program, they are free to relocate elsewhere, and secondary migration to join an already established Iraqi community is common. Of Iraqi immigrants resettled in the United States, approximately 30% are under 15 years old, 50% are 15-44 years old, 15% are 45-64 years old, and 4% are ≥65 years (Figure 4) (18).

Figure 2: Iraqi Refugee Arrivals in the United States, 2008-2023 (N=149,619)

Source: US Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS) (19)

Figure 3: States of Primary Resettlement for Iraqi Refugees, FY 2008-2013 (N=90,607)

Table 1: Top 10 States of primary resettlement for Iraqi refugees

| Top 10 States | Number | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| California | 20,240 | (22) |

| Michigan | 13,860 | (15) |

| Texas | 7,628 | (8) |

| Arizona | 5,574 | (6) |

| Illinois | 5,307 | (6) |

| Massachusetts | 3,152 | (3) |

| Virginia | 2,854 | (3) |

| New York | 2,614 | (3) |

| Washington | 2,374 | (3) |

| Tennessee | 1,933 | (2) |

*The remaining 45,051 refugees resettled in 39 other states.

Source: WRAPS

Figure 4: Age Distribution for Iraqi Refugees Resettled in the United States, 2008-2013 (N=90,607)*

*3,039 refugees of unknown age

Source: CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN) (18)

Health care and conditions in camps or urban settings

In a rapid survey by the Syrian Ministry of Health and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in 2007, the immunization coverage among Iraqi children <5 years old in Syria was 89% for diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT) and Haemophilus influenzae type B (third dose), 82% for measles, and 81% for hepatitis B (20). Upon arrival in Jordan, 52% of Iraqi refugees with children <5 years reported receiving vaccinations (21). Some immunizations that are currently given to refugees in Iraq, Syria, and Jordan can be found in the immunization schedules at CDC: Overseas Refugee Health Guidance.

Reproductive health

In Iraq, approximately 80% of babies were delivered by skilled attendants (doctor, midwife, or nurse), and 18% by traditional birth attendants (9). In Syria, close to 70% of expectant Iraqi mothers delivered in hospitals in 2006, and 93% of births were attended by a physician (22). The information from Syria states the situation before the current civil war, and may not reflect the current situation there. Over 15% of expectant Iraqi mothers in Syria did not receive antenatal care, and 40% of expectant Iraqi mothers in Syria also did not receive tetanus vaccine (22). In Jordan, 94% of Iraqi women who gave birth delivered in a health care facility. Ninety-one percent of pregnant Iraqi women sought antenatal care during their most recent pregnancy, and 48% of them also sought postnatal care. Among the women who did not seek postnatal care, the most common reasons included not perceiving a need for a postnatal visit or not wanting care (21). Knowledge of family planning methods and birth spacing was shown to be high among adult Iraqi refugees in Jordan (23). However, knowledge of family planning and general reproductive health among adolescent Iraqi refugees was low; most group discussions with adolescents yielded knowledge of only one contraceptive method or way to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) besides abstaining from sex (23).

The most commonly used method of family planning among Iraqi refugees interviewed in Jordan was withdrawal (32%), followed by oral contraceptive pills (30%), IUD (22%), rhythm/calendar (21%), and the male condom (21%) (23). Access to family planning is almost nonexistent for poor, unmarried, and adolescent Iraqi refugees. This leads to unsafe abortions or abortions illegally performed by doctors (7). Little information is available regarding the family planning situation for Iraqi refugees in Syria.

Gender-based violence

Iraqi refugee women living in Jordan reported domestic violence as a common occurrence. The stress of living in cramped quarters, the trauma of violence and loss experienced in Iraq, and a lack of employment have all contributed to extensive domestic violence. Additionally, marital rape was reported (24).

Many Iraqi refugee women and girls witnessed or are survivors of sexual violence in Iraq, especially rape by armed groups and civilians (24). Since the Second Gulf War, there has also been an increase in trafficking and sexual exploitation. As many as 15% of Iraqi widows seek “temporary marriages” or transactional sex work for protection and/or financial support. Additionally, approximately 4,000 Iraqi females, many of whom are children, have disappeared and are believed to have been forced into sex work (24).

In Iraq, medical care and psychosocial support for the survivors of sexual violence are not available, so most rapes go unreported (24). Cultural barriers such as stigma and shame also impede Iraqi rape survivors from reporting their attacks (7).

Since the Second Gulf War, chronic food insecurity has become one of the biggest issues affecting Iraqis. As of 2007, only 32% of Iraqis had access to safe drinking water, and lack of adequate sanitation has contributed to diarrheal disease outbreaks, including typhoid and a large outbreak of cholera in October 2007 and more recently (3).

The Iraqi Ministry of Health reported that over half of Iraqi women and children suffer from malnutrition and anemia, contributing to high maternal and infant mortality (30). In 2011, prevalence of acute malnutrition measured by mid-upper arm circumference among Iraqi refugee children <5 years old was 1.7% in Jordan and 4.5% in Syria (5). Food insecurity seems to be of greater concern in Syria than in Jordan. Among Iraqi refugees resettled in San Diego from 2007-2009, 16.5% of children <5 years old and 29.6% of women of childbearing age were anemic (26). In 2012, a CDC survey of Iraqi refugees in 4 US states showed that 9% of participants and 13% of their household members reported having anemia (8).

Medical screening of U.S.-bound refugees

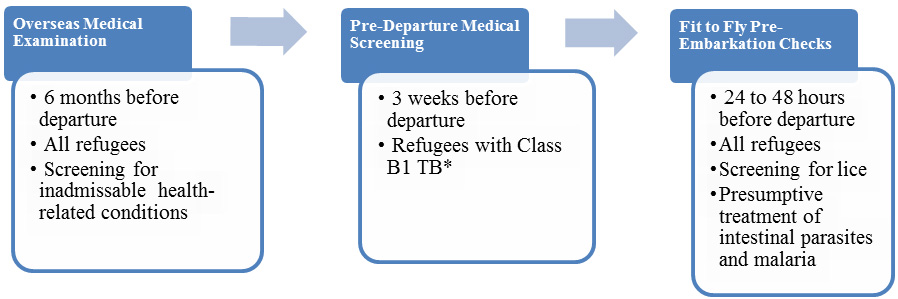

Iraqi refugees who have been identified for resettlement in the United States receive additional medical assessments (Figure 5). As outlined below, some assessments occur several months prior to the refugees’ departure, and some occur immediately before departure to the United States.

Figure 5: Medical Assessment of U.S.-bound Refugees

*Class B1 TB refers to TB fully treated by directly observed therapy, or abnormal chest x-ray with negative sputum smears and cultures, or extrapulmonary TB.

An overseas medical examination (CDC: Overseas Refugee Health Guidance) is mandatory for all refugees coming to the United States and must be performed according to CDC: Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians. The purpose of the medical examination is to identify applicants with inadmissible health-related conditions. Panel physicians, selected by Department of State consular officials, perform these examinations. CDC provides the technical oversight and training for the panel physicians. Information collected during the refugee visa medical examination is reported to CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN) and is available to state health departments where the refugees are resettled. For refugee applicants, panel physicians must complete a US Department of State Vaccination Documentation Worksheet (DS-3025) if reliable documents are available.

In Jordan, a pre-departure medical screening is conducted approximately 3 weeks before departure for the United States for refugees previously diagnosed with class B1 tuberculosis (tuberculosis fully treated by directly observed therapy, or abnormal chest x-ray with negative sputum smears and cultures, or extrapulmonary tuberculosis). The screening includes a repeat physical examination with a focus on tuberculosis signs and symptoms, chest x-ray, and sputum collection.

IOM clinicians perform a pre-embarkation check within 24-48 hours of the refugee’s departure for the United States to assess fitness for travel and administer presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites.

Once refugees have arrived in the United States, CDC recommends that they receive a post-arrival medical screening (CDC: Guidance for the U.S. Domestic Medical Examination for Newly Arriving Refugees) within 30 days after arrival. The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) reimburses providers for screenings conducted during the first 90 days after the refugee’s arrival. The purpose of these more comprehensive examinations is to assess the refugee’s health conditions and to introduce him or her to the US health care system. CDC provides guidelines and recommendations, and state refugee health programs oversee and administer the domestic medical examinations. State refugee health programs or private physicians conduct the examinations. State refugee health programs determine who conducts the examinations within their jurisdiction, and most state refugee health programs collect the data from the screenings.

Health information

This section describes the disease burden for specific diseases among the Iraqi refugee community. The data sources for this section include the International Organization for Migration (IOM), CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN), and data from domestic medical examinations provided by state health departments.

Communicable diseases

According to the WHO Tuberculosis Profile, Iraq reported 8,664 new cases of tuberculosis in 2012 and a prevalence of 73 cases per 100,000 population (27). Within Iraq, 180 new cases of multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis were confirmed as of 2012 (27).

From 2008- 2013, 0.2% of Iraqi refugees arrived in the US with a TB class B1 which is TB fully treated using directly observed therapy, or abnormal chest x-ray with negative sputum smears and cultures, or extrapulmonary TB. Tuberculin skin tests (TST) are routinely performed on children aged 2-14 years and those with a positive TST are designated as TB class B2. Approximately 1% of children examined overseas had a positive TST from 2008-2013.

While national-level data on hepatitis is limited, of 2,957 Iraqi refugees screened for hepatitis B in San Diego as part of the domestic medical examination, 21 (0.7%) were diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B virus infection, which is comparable with the national average of hepatitis B in Iraq (26).

The prevalence of HIV in Iraq is less than 1%, but reported cases have been increasing, especially in areas close to Baghdad (21). According to EDN, of ~91,000 US-bound Iraqi refugees screened from 2008 through 2013 as part of the visa medical exam, 0.1% tested positive for syphilis and were treated prior to arrival.

Non-communicable diseases

Chronic, noninfectious health conditions account for a considerable disease burden among all screened Iraqi refugees (3) (28-30). One study showed that 27% (5,095) of Iraqi refugees screened by IOM in Jordan had at least one chronic condition, including hypertension, elevated cholesterol, elevated blood glucose (or diabetes), ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, or were overweight or obese (28). Among adult Iraqi refugees screened in California, the most commonly diagnosed chronic conditions were obesity (25%) and hypertension (15%) (26). Other chronic conditions included vision problems; ear, nose, and throat problems (5%); hearing problems (2%); and asthma (2%), arthritis, dental caries, asthma, goiter, hernia, skin allergies, and epilepsy (26).

Breast cancer was the most common cause of cancer morbidity among Iraqi refugee women screened outside of Iraq. From 1985-2001 breast cancer was the leading cause of death among Arab-American women in Michigan (31). Although many Arab-American women indicated that their health insurance covered cancer screening, they either had low screening rates or delayed screening (32) (33). Availability of health insurance coverage may not be the only barrier to timely cancer screening. Other barriers may include transportation, language, and beliefs about cancer causation and prevention (32) (33). Health care providers should be aware of the health perspectives of newly resettled Iraqi refugees and should provide cancer education materials in Arabic to encourage timely screening.

Blood pressure is measured during the visa medical exam and during domestic medical examinations in the United States. Although two or three measurements are required to diagnose an individual with hypertension, single measurements may be used to estimate prevalence of hypertension in a population. In Jordan, of 13,299 US-bound screened Iraqis ≥15 years of age, 33% (4,382) had hypertension. An additional 42% (5,565) of Iraqi refugees were pre-hypertensive (28). Of Iraqi refugees ≥15 years of age arriving to the US from 2008- 2013, 10% self-reported having a history of hypertension.

Of the 18,990 Iraqi refugees screened in Jordan in IOM clinics from 2007 through 2009, 514 (3%) were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. Of these, 11% (58) had type I and 89% (456) had type II diabetes. Of those who were diagnosed with diabetes, 84% (343) had hypertension, 22% (113) had pre-hypertension, and 2% (8) had hypertension and a history of angina or myocardial infarction (28).

Obesity is a major health issue impacting this population. Of the 11,898 Iraqi refugees ≥ 20 years of age with available weight and height information screened in IOM clinics in Jordan, 38% (4,495) were overweight (BMI = 25.5-29.9 kg/m2), and 34% (3,982) were obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). Of those who were overweight, 35% (1,581) also had hypertension and of those who were obese, 50% (2,006) had hypertension. Of 5,734 Iraqi refugees 2-19 years of age with available weight and height information, 10% (572) were underweight (<5% of BMI for age), 14% (820) were overweight (85%-95% of BMI for age), and 11% (632) were obese (28).

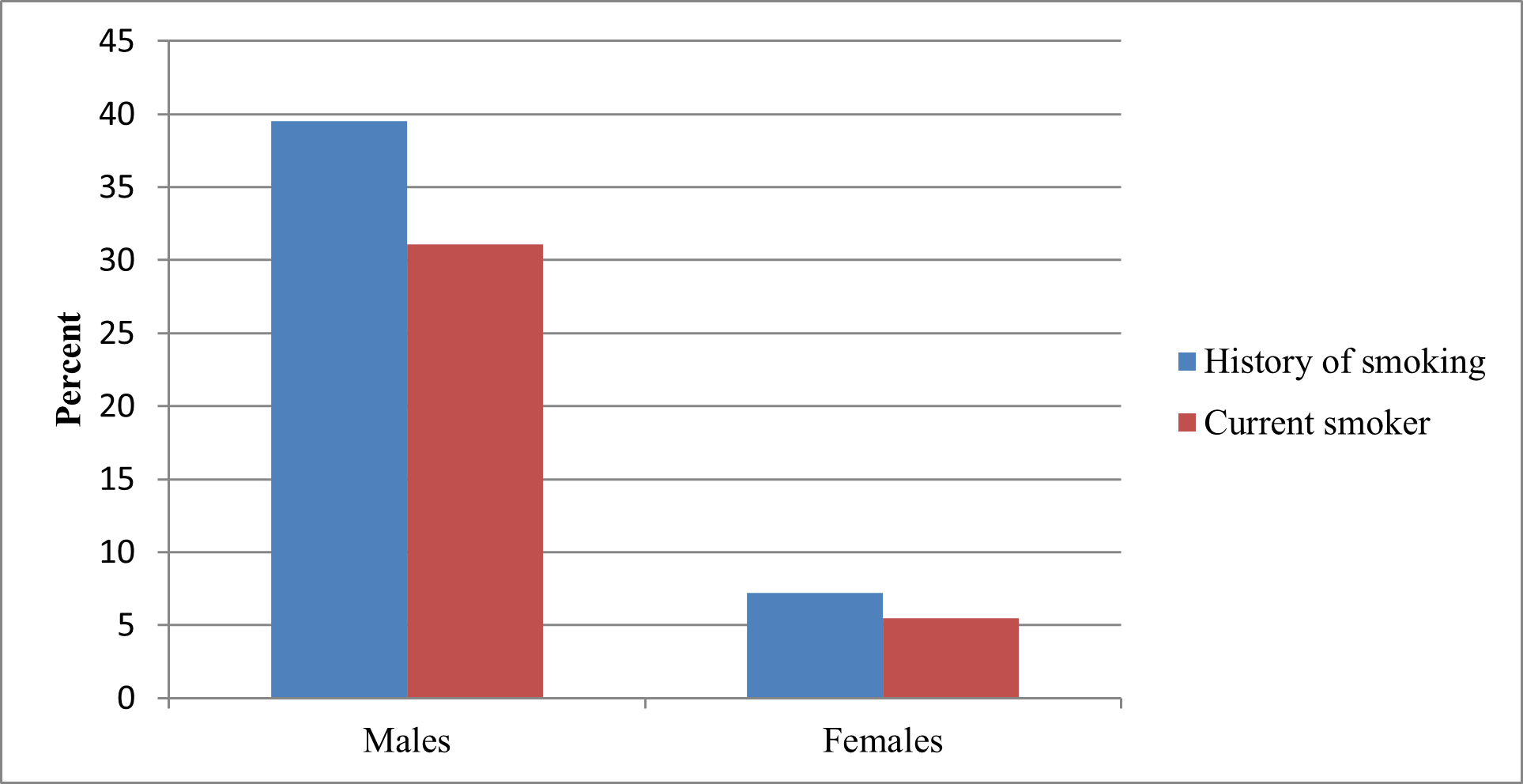

Smoking is widely accepted among Iraqis, particularly Iraqi men (Figure 6). Of Iraqi male refugees ≥15 years old who arrived in the US from 2008 - 2013, 40% had a history of smoking and 31% were current smokers. Smoking among Iraqi women was less common than among Iraqi men.

Figure 6: Self-reported tobacco use among Iraqi refugees during visa medical examinations at panel physician sites, 2008-2013 (N=63,322)

Source: CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification system (EDN) (18)

Congenital and genetic disorders are a concern among the Iraqi population. Of the 18,990 screened refugees, 1.7% (325) had congenital disorders: 0.1% (16) had congenital cardiovascular defects, 0.2% (33) had glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, 0.02% (4) had sickle cell disease, 7 (0.03%) thalassemia, and 116 (0.6%) congenital hemangioma. The Iraq Family Health Survey reported that 37% of Iraqi women are married to their cousins and 23% to other relatives, which may partially account for the high prevalence of certain recessively inherited disorders (9) (28). Health care providers serving Iraqi families should inquire about consanguinity and become familiar with the genetic disorders common among Arabs, such as G6PD deficiency, sickle cell disease, and thalassemia (28).

Iraqi refugee children specifically do not appear to be at higher risk of lead poisoning than US children. Only 1.3% of Iraqi children ≤5 years of age screened in San Diego during 2008–2009 had elevated blood lead levels (≥10 µg/dL) (26). However, refugee children in general are thought to be at higher risk for lead poisoning, not only because anemia and malnutrition increase lead absorption, but also because of an increased risk for exposure to products containing lead.

According to the International Rescue Committee (IRC), Iraqi refugees arrive in the United States with more emotional and mental health issues than many other refugee groups, and the IRC has documented a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among recently arrived Iraqis (30). In a 2012 CDC survey of Iraqi refugees who had lived in the United States 8-36 months, 50% of participants reported anxiety, 49% depression, and 31% a need for further assessment for PTSD (8). This finding is consistent with data collected on Iraqis in their host countries. In Syria, 89.5% of interviewed Iraqi refugees reported depression, 81.6% anxiety, and 67.6% PTSD (6). Reasons reported for mental health issues among Iraqis in Syria included air bombardments, shelling, or rocket attacks (77%); witnessing a shooting (80%); interrogation or harassment by militias (68%); and knowing someone close to them who had been killed (75%) (6).

A 2009 study estimated the lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder at 18.8% for Iraqi adults (34). Anxiety disorders were the most common (13.8%) class of disorders in the cohort studied, and major depressive disorder (MDD) was the most common (7.2%) single disorder (34). Iraqi refugees are aware of their psychological disturbances and describe their feelings of anxiety and depression in terms such as “Dayij” (uncomfortable), “Ka’aba” (melancholia), “al Zillah” (humiliation), “Kalak” (anxiety), “Inziaaj” (uneasiness), “Ihbat” (frustration), “Khawf” (fears), “Daghet” (pressure), “Ta’ab” (tiredness), “Sadma” (shocked), “Insilakh” (uprooting), and “Hasbiya Allah wa ni’ma l wakil” and “Allah y’in”, which both refer to the hope in God’s assistance to face trouble and injustice (17). Iraqi refugees may not seek mental health care due to cultural stigmatization of mental health patients; lack of access to mental health services in countries of asylum (especially Jordan); and lack of outreach and education about mental health issues (17). Iraqi refugees may manifest mental health problems as physical symptoms, such as headaches, backaches, body aches, or gastrointestinal problems with no physical underlying reasons.

Summary

Iraqi refugees have been coming to the United States for a short time compared with some other refugee groups. Iraqi refugees have a high burden of non-communicable disease such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and malnutrition. The information provided above is intended to help resettlement agencies, clinicians, and health care providers understand the cultural background and health issues of greatest concern pertaining to resettling Iraqi refugee populations.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR Iraq Fact Sheet. 2010. Accessed November 2013. http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e486426.html

- Queensland Health Multicultural Services. Community Profiles for Healthcare Providers: Iraqi Australians. Queensland Health. [Online] July 8, 2011. [Cited: September 13, 2011.] www.health.qld.gov.au/multicultural.

- Giese, Amanda. An Assessment of the Health of Iraqi Refugees in Chicago. Heartland Alliance. 2010.

- Harper, Andrew. Iraq's Refugees: Ignored and Unwanted. 869, 2008, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 90, pp. 169-190.

- Doocy, Shannon, et al. Food Security and Humanitarian Assistance Among Displaced Iraqi Populations in Jordan and Syria. 2, 2011, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 72, pp. 273-282.

- Ghareeb, Edmund, Ranard, Donald and Tutunji, Jenab. Refugees from Iraq: Their History, Cultures, and Background Experiences. Center for Applied Linguistics. 2008. COR Center Enhanced Refugee Backgrounder No. 1.

- Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children. Iraqi Refugee Women and Youth in Jordan: Reproductive Health Findings, A Snapshot from the Field. 2007.

- Taylor, Eboni et al. Physical and Mental Health Status of Iraqi Refugees Resettled in the United States. Springer, Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, August, 2013. Web. August, 2013.

- Iraq Family Health Survey 2006/7 (World Health Organization). Accessed 2012, at http://www.emro.who.int/iraq/pdf/ifhs_report_en.pdf).rm

- Terrazas, Aaron. Iraqi Immigrants in the United States. Migration Information Source. [Online] March 5, 2009. [Cited: September 9, 2011.] http://www.migrationinformation.org/USfocus/display.cfm?id=721.

- O'Donnell, Kelly and Newland, Kathleen. The Iraqi Refugee Crisis: The Need for Action. Migration Policy Institute. 2008.

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Tips for Health Care Providers about Iraqi Refugees. 2010.

- Stratis Health. Iraqis in Minnesota. Stratis Health. [Online] 11 1, 2009. [Cited: September 13, 2011.] http://www.stratishealth.org.

- Saadi, Altaf, Bond, Barbara and Percac-Lima, Sanja. Perspectives on Preventive Health Care and Barriers to Breast Cancer Screening Among Iraqi Women Refugees. 2011, Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. PMID 21901446 .

- IRC Commission on Iraqi Refugees. A Tough Road Home: Uprooted Iraqis in Jordan, Syria and Iraq. New York : International Rescue Committee, 2010.

- Frelick, Bill. "The Silent Treatment": Fleeing Iraq, Surviving in Jordan. [ed.] Peter Bouckhaert, Christoph Wilcke and Sarah Leah Whitson. Human Rights Watch. November 2006, Vol. 18, 10.

- Schinina, et al. Assessment on Psychosocial Needs of Iraqis Displaced in Jordan and Lebanon. International Organization for Migration. 2008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012), Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN).

- US Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS).

- Joint Appeal by UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO. Meeting the Health Needs of Iraqis Displaced in Neighbouring Countries. 2007.

- World Health Organization/UNICEF/Johns Hopkins University. The Health Status of the Iraqi Population in Jordan: 2009

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; United Nations Children's Development Fund; World Food Program. Assessment on the Situation of Iraqi Refugees in Syria. 2006.

- Women's Refugee Commission. Baseline Study: Documenting Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Iraqi Refugees and the Status of Family Planning Services in UNHCR's Operations in Amman, Jordan. 2011.

- Chynoweth, Sarah. The Need for Priority Reproductive Health Services for Displaced Iraqi Women and Girls. 31, 2008, Reproductive Health Matters, Vol. 16, pp. 93-102.

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO) website. Accessed September, 2012. http://www.emro.who.int/

- Ramos, M, et al. Health of Resettled Iraqi Refugees--San Diego County, California, October 2007-September 2009. 2010, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 59, pp. 1614-1618.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Profile: Iraq. World Health Organization. [Online] January, 29th 2013. [Cited: January 29th, 2013] www.who.int/tb/data.

- Yanni, E, et al; The Health Profile and Chronic Diseases Comorbidities of US-Bound Iraqi Refugees Screened by the International Organization for Migration in Jordan: 2007–2009. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health; DOI 10.1007/s10903-012-9578-6

- World Health Organization. Non-Communicable Disease Profile: Iraq. World Health Organization. [Online] September 12, 2011. [Cited: September 12, 2011.] http://Infobase.who.int.

- International Rescue Committee. The Health of Refugees from Iraq. 2009. http://www.rescue.org/iraqi-refugees.

- Darwish-Yassine M, Wing D. Cancer epidemiology in Arab Americans and Arabs outside the Middle East. Ethn Dis. 2005;15 (1 Suppl 1):S1-5–S1-8.

- Michigan Department of Community Health. Color me healthy: a profile of Michigan’s racial/ethnic populations, May 2008. 2011. Accessed on 22 Jan 2011 at http://www.michigan.gov/

documents/mdch/ColorMeHealthyProfileMay2008_2362457.pdf. - Shah SM, et al. Arab American Immigrants in New York: health care and cancer knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10:429–36.

- Alhasnawi, Salih, et al. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the Iraq Mental Health Survey (IMHS). 2, 2009, World Psychiatry, Vol. 8, pp. 97-109.

35. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2013 UNHCR country operations profile - Iraq. http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e486426.html