Center of Excellence in Newcomer Health

- Minnesota Center of Excellence in Newcomer Health Home

- About

- Clinical Guidance and Clinical Decision Tools

- Health Education

- Publications and Presentations

- Trainings

- Newcomer Health Profiles

Spotlight

- Haitian Clinical Guidance

- OB-GYN Care for Afghans: A Toolkit for Clinicians

- Immigrant Health Matters

- Newcomer Education for Wellness Video Series

- MNCOE Connect

Related Topics

Syrian Refugee Health Profile

Last updated: March 2024

Last updated: March 2024

On this page:

Priority health conditions

Background

Population movements

Health care access and health concerns

Medical screening of U.S.-bound refugees

Health information

Summary

References

Priority health conditions

The health conditions listed below are considered priority health conditions in caring for or assisting Syrian refugees. These health conditions represent a distinct health burden for the Syrian refugee population.

Background

The Syrian Arab Republic (Syria) is located in the Middle East bordering Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, and Israel; it is also bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the west (Figure 1). Syria is largely a semiarid or arid plateau, and encompasses various mountain ranges, desert regions, and the Euphrates River Basin [1].

Figure 1: Map of Middle East

Source: Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ), CDC

Syria is a presidential republic. In 2000, Bashar al-Assad assumed power as the President of Syria, Commander-in-Chief of the Syrian Armed Forces, and General and Regional Secretary of the Ba’ath Party, following the death of his predecessor and father, Hafez al-Assad. President Assad is currently serving his third term.

In March 2011, pro-democracy protests began in Daraa, following the arrest and torture of several Syrian teenagers. Government security forces opened fire on demonstrators, resulting in nationwide protests calling for President Assad’s resignation. Violence escalated, and Syria quickly dissolved into civil war [2].

What started as political dissonance has bourgeoned into a violent proxy war involving local, regional, and world players. The conflict in Syria has become largely sectarian, with the Sunni majority posed against the Shia Alawite minority. Jihadist groups, including the Islamic State, a group originating from al-Qaeda in Iraq, have taken control of large areas in northern and eastern Syria, as well as territory in Iraq. International forces including the United States, France, and the United Kingdom are also involved [2].

More than 250,000 people have been killed since fighting erupted in 2011 [2]. As of 2013, the Middle East has the highest number of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) of any region worldwide [3]. Syria had a pre-war population of 22 million and currently has a population of approximately 17 million people, with an estimated 5 million fleeing the country [4, 5]. Since the conflict began, more than half the population (~ 12 million) are considered displaced [6].

The world is currently witness to the largest refugee exoduses since World War II, with Syrian refugees flooding into neighboring countries of Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey [2]. Syrian refugees have also fled to the European Union. Between April 2011 and October 2015, 681,713 Syrians applied for asylum in one of 37 European nations [7].

Approximately 90% of Syrians are of Arab descent, and roughly 9% are Kurds. The remaining 1% of the population are Armenian, Circassian, and Turkoman [1, 8].

Arabic, the official language of Syria, is spoken by approximately 90% of Syrians. The majority of Syrians speak colloquial Arabic, and read and write Modern Standard Arabic [9]. Circassian, Kurdish, Armenian, Aramaic, Syriac, French, and English are also spoken. French and English are widely understood, particularly among educated groups in urban areas [1]. While many Syrian refugees have a basic knowledge of English, relatively few are proficient [9].

Prior to the conflict, Syria had one of the strongest education programs in the Middle East, with 97% of primary-age children attending school [10]. The collapse of the Syrian education system is most notable in areas of intense violence. Less than half of all children in Al-Raqqa, Idlib, Aleppo, Deir Azzour, Hama and Darra’a attend school. School attendance in Idlib and Aleppo has plunged below 30% [10].

It is estimated that between 500,000 and 600,000 Syrian refugee children in the Middle East and North Africa have no access to education [10]. However, it is likely that the number of children with no access to learning is considerably higher, as these figures only account for registered refugees [10].

Overall literacy in Syria is estimated at 86.4%, with 91.7% of men and 81% of women being able to read and write [8]. Youth literacy is estimated at 95.9% [4]. Overall, men tend to have higher literacy rates than women, and Syrian youths tend to have higher literacy rates than adults.

Islam is practiced by 90% of the population. Approximately 74% of the total population are Sunni and 16% are Alawite, Druze, or Ismaili [9]. Minority religious groups include Arab Christians (Greek Orthodox and Catholic), Syriac Christians, Aramaic-speaking Christians, and Armenian Orthodox and Catholics [9]. These minority groups account for 10% of the population. There is also a small Kurdish-speaking Yazidi community [9].

The typical Syrian family is large and extended. Families are close-knit, protecting the family’s honor and reputation is important. Like many Arab societies, Syrian society is patriarchal. Women are believed to require protection, particularly from the unwanted attention of men. Generally, an elderly male has ultimate decision-making authority and is seen as the family protector [9].

Gender roles may vary by economic class, level of education, family, and rural or urban residency. Women, especially from religiously conservative families, are typically responsible for cooking, cleaning, and caring for children, while men are typically responsible for supporting the family financially. Among the upper classes, women are well educated and often work outside the home. However, women from middle-class urban and rural households are expected to stay home and care for children, while women from poor families often work in menial, low-wage jobs. [9].

Syrians are familiar and tend to engage with the Western medical modal. Syrians will often seek immediate medical care for physical injury or illness, are anxious to begin treatment, and will generally listen to their physician’s advice and instructions. They tend to see physicians as the decision makers and may have less confidence in non-physician health professionals. Although most Syrians are familiar with Western medical practices, like most populations, they tend to have certain care preferences, attitudes, and expectations driven by cultural norms and expectations [9].

For example, Syrian patients or their families might be more likely than the general US patient population to:

- Prefer a provider of the same gender [9, 11]

- Request long hospital gowns for modesty (especially female patients) [9, 11]

- Request meals in accordance with Islamic dietary restrictions (Halal) during hospital stays or request family to bring specific meals or foods [9, 11]

- Fast or refuse certain medical practices (e.g. to take oral medication) during certain periods of religious observance such as the month of Ramadan [9]

- Be less likely to consider conditions chronic in nature (they may cease taking medications if symptoms resolve and be more likely not return for follow-up appointments if not experiencing symptoms [9]

- Not be open to questions or discussions regarding certain sensitive issues—particularly those pertaining to sex, sexual problems, or sexually transmitted infections [9]

- Refuse consent for an organ donation (or autopsy) since it is commonly felt by Syrian Muslims that the body is a gift [11]

Historically, there has been stigma surrounding mental health in the Syrian community. Syrians have been resistant to acknowledging mental health issues as it is considered a personal flaw and might bring shame on family and friends. As a result, individuals are often reluctant to seek professional psychological or psychiatric help. However, with the more recent rise in generalized mental health trauma some have reported that Syrian refugees are becoming more open and accepting of mental health conditions and treatment [9].

For more information about the orientation, resettlement, and adjustment of Syrian refugees, visit EthnoMed: Nepali-Speaking Bhutanese.

Population movements

Syria has one of the lowest net migration rates in the world at -19.79 migrants per 1,000 population [8]. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that there are 149,140 refugees and 2,745 asylum seekers residing in Syria. Additionally, UNHCR estimates that there are 7,632,500 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Syria [6]. The conflict in Syria has produced 4,287,293 registered Syrian refugees [12]. Approximately 2.1 million Syrian refugees have been registered by UNHCR in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon, while 1.9 million have been registered in Turkey [12]. An additional 26,700 refugees have been registered in North Africa [12]. In total, nearly 12 million persons have been directly affected by the conflict in Syria [6].

To Iraq

As of February 2016, nearly 250,000 Syrian refugees were living in Iraq [12]. Of those living in Iraq, 62% were residing outside of camps, while the remaining 38% residing in refugee camps [15].

To Jordan

As of February 2016, more than 630,000 Syrian refugees were living in Jordan [12]. Of those living in Jordan, the majority of refugees (82%) were living in urban areas or in informal settlements [15].

To Lebanon

Since conflict erupted in Syria, Lebanon has received nearly 1.1 million Syrian refugees, none of which are living in refugee camps [12].

To Turkey

As of February 2016, more than 2.6 million Syrian refugees have entered Turkey [12], most of them living in urban areas.

To Egypt and North Africa

As of February 2016, more than 118,000 Syrian refugees have arrived in Egypt, as well as nearly 27,000 in North Africa [12].

Relatively few Syrians have been resettled in the United States as refugees. However, Syrians began arriving in the United States as immigrants in the late 1800s. The first wave of immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa continued into the mid-1920s. This initial wave of immigrants consisted largely of Arab Christians from the Ottoman Empire and the Province of Syria, now modern day Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and Syria [13]. From 1899-1932, 106,391 Syrians immigrated to the United States [14]. A second wave of Syrian immigrants began in 1948, and continued through 1965. According to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, more than 310,000 Arabs entered the United States from 1948-1985, of which, 60% were Muslim [14].

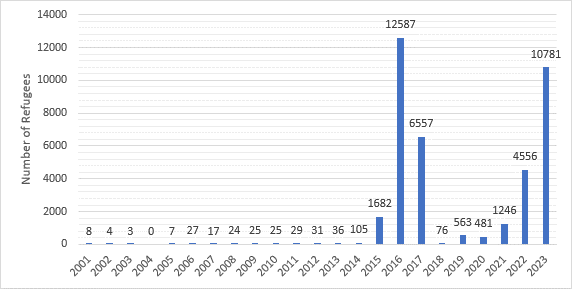

Prior to 2014, the United States Refugee Resettlement Program formally resettled few Syrian refugees. From 2008-2013, the United States resettled between 24 and 36 Syrian refugees each year (Figure 3). That number rose to 1,682 in 2015, 12,587 in 2016, and 12,587 in 2017. From 2018 through 2020, there again were relatively few arrivals (rough 1,100). However, from 2021 through 2023, there was another spike in arrivals, comparable to the 2015-2017 number (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Syrian Refugee Arrivals in the United States, 2008-2023 (N=38,870)

Source: US Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS) (Refugee Admissions Report 2023_11_30)

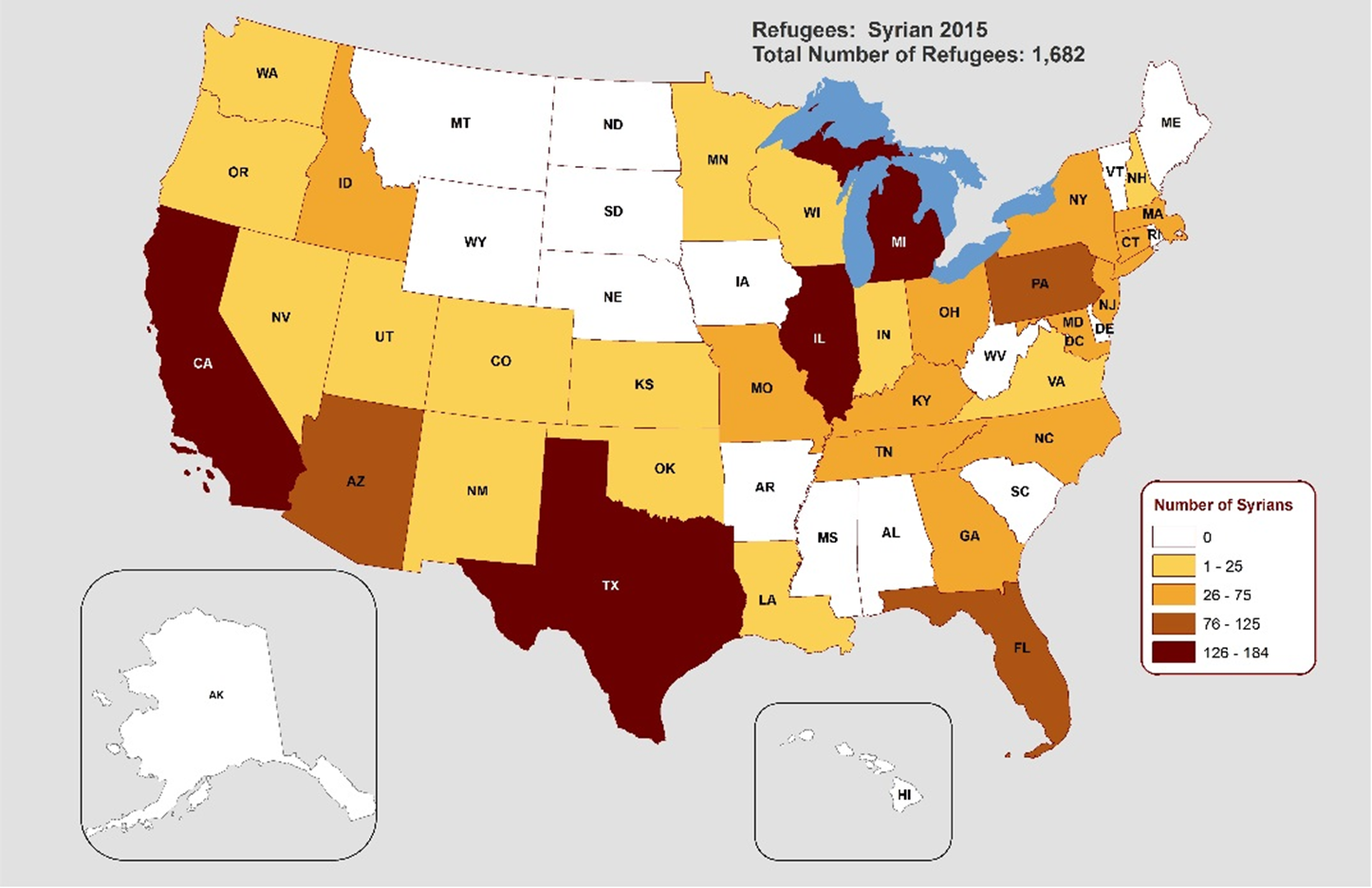

Figure 3: States of Primary Resettlement for Syrian Refugees, FY 2015 (N=1,682)

Table 1: Top 10 States of primary resettlement for Syrian refugees

| Top 10 States | Number | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Texas | 184 | (10.9) |

| California | 179 | (10.6) |

| Michigan | 179 | (10.6) |

| Illinois | 134 | (8.0) |

| Arizona | 125 | (7.4) |

| Pennsylvania | 111 | (6.6) |

| Florida | 98 | (5.8) |

| New Jersey | 73 | (4.3) |

| Massachusetts | 70 | (4.2) |

| Kentucky | 61 | (3.6) |

| Georgia | 53 | (3.2) |

*The remaining 415 refugees resettled in 22 other states.

Source: WRAPS

Health care access and health concerns

Prior to the civil disturbance, Syria was a relatively affluent society and a majority of Syrian refugees were from relatively higher socioeconomic backgrounds. As a result, the health conditions observed in this population reflect chronic conditions not as often associated with recent refugees (e.g., hypertension, diabetes and cancer). In addition, acute illnesses and infectious diseases tend to reflect the process of displacement, crowding and sanitation (e.g., trauma, tuberculosis, respiratory and diarrheal diseases).

Access to health care varies greatly depending on country of asylum and whether a refugee lives in a refugee camp or in an urban or informal settlement. UNCHR reported that the majority (89.6%) of primary health care visits were due to communicable diseases in Iraqi refugee camps [15]. Non-communicable diseases (7.4%), injuries (2.5%), and mental illness (0.5%) were also noted as reasons for seeking primary care [15]. Similarly, the majority of primary health care visits in Zaatari Camp (Jordan) and Lebanon were due to communicable diseases [15]. Notably, 21.8% of primary health care visits were attributed to non-communicable diseases in Zaatari Camp, while Iraq and Lebanon reported non-communicable diseases accounted for 7.4% and 8.3% of all primary health care visits, respectively [15].

Some immunizations that are currently given to refugees in Iraq, Syria, and Jordan can be found in the current immunization schedules at CDC: Vaccination Program for U.S.-bound Refugees.

Reproductive health

Since the Syrian crisis began in 2011, women have lacked access to reproductive health needs. A 2012 study assessing health of women presenting to 6 regional primary health care clinics in Lebanon found that out of 452 women aged 18-45 years old, 65.5% were using no form of birth control. Of this group, the mean age of first pregnancy was 19 years old, 16.4% were pregnant during the current conflict, and 17.7% reporting at least 1 child death. Of note, 27.4% of these women were diagnosed with anemia, 12.2% with hypertension, 3.1% with diabetes, and 51.6% reported dysmenorrhea or severe pelvic pain [16].

In Jordan’s health system, family planning is an integrated part of care, however, it is only provided to married couples [17]. In a 2013 study of 101 15-49 year old women in the Zaatri Refugee Camp, where birth control is offered, only 1 in 3 women knew about birth control options in the camp and in focus groups with these women, they believed that the most common age to marry was at age 15 years [17]. A 2014 study evaluated 1550 households in Jordan (9580 individuals) and demonstrated that the majority of women (82.2%) received antenatal care with an average of 6.2 visits and that 82.2% delivered their infants in the hospital (Syrian Refugee Health Access Survey in Jordan, 12/2014).

Many Syrian refugees view decisions around contraception as one made by the man and woman together. When offering education around birth control, consider providing contraception counseling to individual women, and with her consent, including her male partner in these discussions [18].

Gender-based violence

Sexual violence is of concern for women and girls in Syria, as well as countries of first asylum. Fear of sexual violence from other refugees or host country nationals may cause Syrian refugee women to stay home, and only venture outside when accompanied by family members [9]. A 2012 study performed in Lebanon of 452 Syrian refugee women found that 30.8% had reported exposure to abuse and violence, including sexual violence, with many reporting multiple events [16].

Medical screening of U.S.-bound refugees

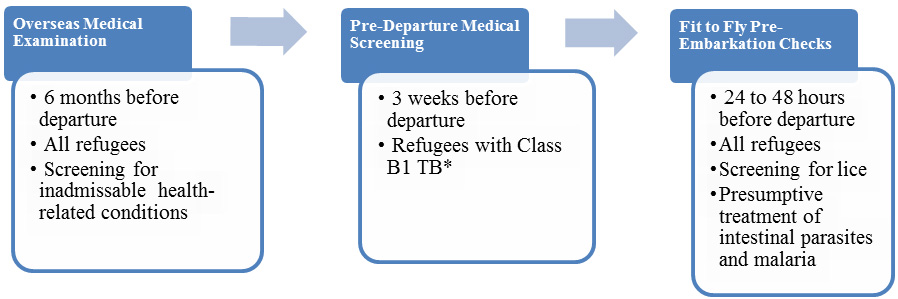

Syrian refugees who have been identified for resettlement in the United States receive additional medical assessments (Figure 5). As outlined below, some assessments occur several months prior to the refugees’ departure, and some occur immediately before departure to the United States.

Figure 4: Medical Assessment of U.S.-bound Refugees

*Class B1 TB refers to TB fully treated by directly observed therapy, or abnormal chest x-ray with negative sputum smears and cultures, or extrapulmonary TB.

A visa medical examination (CDC: Refugee Health Overseas Guidance) is mandatory for all refugees coming to the United States and must be performed according to CDC: Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians. The purpose of the medical examination is to identify applicants with inadmissible health-related conditions. Panel physicians, selected by Department of State consular officials, perform these examinations. CDC provides the technical oversight and training for the panel physicians. Information collected during the refugee visa medical examination is reported to CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN) and is available to state health departments where the refugees are resettled. For refugee applicants, panel physicians must complete a US Department of State Vaccination Documentation Worksheet (DS-3025) if reliable documents are available.

In Jordan, a pre-departure medical screening is conducted approximately 3 weeks before departure for the United States for refugees previously diagnosed with class B1 tuberculosis (tuberculosis fully treated by directly observed therapy, or abnormal chest x-ray with negative sputum smears and cultures, or extrapulmonary tuberculosis). The screening includes a repeat physical examination with a focus on tuberculosis signs and symptoms, chest x-ray, and sputum collection.

IOM clinicians perform a pre-embarkation check within 24-48 hours of the refugee’s departure for the United States to assess fitness for travel and administer presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites.

Once refugees have arrived in the United States, CDC recommends that they receive a post-arrival medical screening (domestic medical examination) within 30 days after arrival. The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) reimburses providers for screenings conducted during the first 90 days after the refugee’s arrival.

The purpose of these more comprehensive examinations is to assess the refugee’s health conditions and to introduce him or her to the U.S. health care system. CDC provides guidelines and recommendations, and state refugee health programs oversee and administer the domestic medical examinations. State refugee health programs or private physicians conduct the examinations. State refugee health programs determine who conducts the examinations within their jurisdiction, and most state refugee health programs collect the data from the screenings.

Health information

This section describes the disease burden for specific diseases among the Syrian refugee community. The data sources for this section include the World Health Organization (WHO), International Organization for Migration (IOM), CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN), and data from domestic medical examinations provided by state health departments.

Communicable diseases

According to the WHO Tuberculosis Profile, Syria reported 3,481 new and relapsed cases of tuberculosis in 2014 and a prevalence of 19 cases per 100,000 population. Within Syria, 226 new cases of multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis were confirmed as of 2014 [19]. A recent investigation by CDC done in Jordan found that the rate of tuberculosis disease detection has been increasing with the acute displacement having increased from 0.73/100,000 per month prior to July 2013 to 1.01/100,000 per month after July 2013. [20] Arrival data to the U.S. indicates that approximately 10% of new arrival Syrian refugees have LTBI detected by IGRA or TST. In Texas (2012-2015) the rate was 10% with 17 testing positive of 164 tested while in Illinois (2012-2015), 9.4% tested positive (20/212).

Chronic infectious hepatitis (B & C) appears to be low. Chronic hepatitis B infection is likely under 2% (new Syrian refugee arrivals from 2012-2015 to Texas, 1.3% (2/156), and to Illinois, <1% (1/208). Until more data is available Syrian refugees should continue to be screened for chronic hepatitis B infection, although if confirmed to be below 2%, guidance may be changed in the future.

Few refugees were screened for hepatitis C, but of 17 screened (likely due to risk factors), 0 tested positive. Hepatitis C rates have been found to be low in Syria (0.4%) as well as surrounding countries (Iraq 0.2%, Jordan 0.3%, Lebanon 0.2%) [21]. Although screening is reasonable, it is not currently routinely recommended in Syrians without risk factors or who do not fall into currently screened populations in the U.S. Those with risk factors or those where routine screening in the U.S. is recommended (e.g. born during 1945-1965) should undergo screening as currently recommended (CDC: Viral Hepatitis | Refugee Health Domestic Guidance).

HIV and syphilis appear to be uncommon in Syrian refugees. In Texas (2012-2015), 0.6% tested positive for HIV (1/156) and 1.1% (1/92) tested positive for syphilis (non-treponemal). In Illinois (2012-2015), there were no positive tests for either HIV or syphilis in 212 persons screened.

The Syrian refugees are receiving pre-departure albendazole for soil-transmitted helminthic infection, and ivermectin for strongyloidiasis. The prevalence of intestinal parasites appears to be low with only 3 of 104 (~2.9%) tested by ova and parasite screening found to have a potentially pathogenic parasite following arrival (based on Texas and Illinois data 2012-2015). Routine post-arrival stool ova and parasite testing is likely not cost-effective for this population.

Giardia has been detected in Syrian refugees and can be associated with subtle symptoms such as abdominal complaints, loose stool, flatulence, and eructation. In addition, it has been associated with failure to thrive in children. Given young children may not verbalize symptoms or express overt signs, it is reasonable to screen children, particularly those under 5 years of age. When screening is performed, stool antigen testing is more sensitive and convenient than stool ova and parasite examination.

Leishmaniasis is endemic to Syria. Both L. tropica and L. major have been reported in Syrian refugees to Lebanon [22]. A total of 1033 new cases of leishmaniasis were reported in 2013 in Lebanon, with approximately 97% cases occurring in Syrian refugees [23]. Cutaneous leishmanisasis has been also reported in refugees in Turkey [24] [25].

Leishmaniasis is caused by infection with Leishmania parasites, which are spread by the bite of phlebotomine sand flies. There are several different forms of leishmaniasis in people. The most common forms are cutaneous leishmaniasis, which causes skin sores, and visceral leishmaniasis, which affects several internal organs (usually spleen, liver, and bone marrow). The most common form of leishmaniasis in Syrian refugees is the cutaneous form. Currently, there is no additional screening recommended to detect leishmaniasis, however, clinicians should be aware of the disorder and consider it in the differential diagnosis of any Syrian with chronic skin sores or other symptoms that might indicate infection (e.g. splenomegaly, chronic anemia, failure to thrive). Information of diagnosis and management may be accessed at the CDC: Clinical Care of Leishmaniasis website.

Echinococcosis is classified as either cystic or alveolar echinococcosis. The primary form in Syrian refugees is Cystic echinoccosis (CE), also known as hydatid disease. It is caused by infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, a ~2-7 millimeter long tapeworm found in dogs (definitive host) and sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs (intermediate hosts). Although most infections in humans are asymptomatic, CE causes harmful, slowly enlarging cysts in the liver, lungs, and other organs that often grow unnoticed and neglected for years. The presentation is highly variable with most clinical presentation is usually due to mass effect—as the cyst grows it impinges on local tissues causing discomfort and/or abnormal test results such as increased liver function tests. It may also be incidentally noted when diagnostic procedures are done for other reasons (e.g. chest x-ray). Cyst rupture may result in anaphylactic reactions, including death, when the contents of the cyst are released. This can occur spontaneously, following trauma or, importantly, when clinical evaluation/intervention is being attempted.

Currently, no additional screening is recommended for asymptomatic refugees, however, when a cystic lesion is noted this diagnosis should be considered and expert advice should be obtained prior to performing any invasive diagnostic or intervention procedures. Further information is available from the CDC: Clinical Overview of Echinococcosis website.

Non-communicable diseases

Chronic diseases and non-communicable conditions have been reported including cancer, hypertension, diabetes, malnourishment and obesity, renal disease, and hemoglobinopathies/thalessemias.

Prior to the crisis in Syria, 56.1% of the population lived in urban areas and the majority of deaths were secondary to non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular and chronic respiratory disease, cancer and diabetes. Data from 2008 showed that approximately 25% of the adult population suffered from hypertension and 27% from obesity [26]. However, given that Syria has never maintained a national registry of non-communicable disease and deaths, these numbers are only estimates.

In a review of medical issues in over 3,000 adult Syrian refugees living in Jordan and Lebanon, 15.6% identified suffering from a chronic disease, with diabetes, cardiovascular and lung disease being the most common [27].

No national data exists on prevalence of renal disease in the Syrian population. In a 2006 pre-crisis cross-sectional survey of 5 hemodialysis sites in Aleppo, Syria (2006 population of 2.5 million), 550 patients, age range 5-82 years (mean 44.7, median 45 years) were receiving hemodialysis. The top 3 causes of end-stage renal disease in this population were hypertension (21.1%), glomerulonephritis (20.5%), and diabetes (19.5%). Hereditary causes were identified in 6.2% of this group. The low rate of hemodialysis in Aleppo was attributed to high cost, high mortality and low rates of ultimate transplantation [28].

Approximately 5% of the Syrian population are carriers of Beta thalassemia trait and less than 1-5% are carriers of alpha thalassemia trait [29]. Sickle cell disease is reportedly quite uncommon, with <1% of the population found to be carriers [30]. G6PD deficiency has been reported in 3% of the Syrian population [31].

Prior to the crisis in Syria, there was a very high rate of tobacco product usage. A 2006 study showed that 60% of men and 17% of women smoked cigarettes and 20% of men and 5% of women used water pipes (hookahs or nargiles) [32].

The most commonly noted inherited disorder in the Syrian population is Familial Mediterranean Fever, an autosomal recessive inflammatory disease causing periodic fever and pain in serosal membranes, including those of the abdomen, chest and joints. In a 2006 study in Syria, 83 patients with the disease and 242 healthy patients were studied. The mean age of disease onset was 14 years of age with a male to female preponderance of 4:1. Of 242 healthy patients, 17.5% were identified as carriers [33].

Increased blood lead levels appears to be uncommon in Syrian children. Of those 6 months-16 years of age arriving in Texas (2012-2015) one had levels greater than 5 Mcg/dL of 86 tested, while in Illinois (2012-2015) there were no elevated levels detected in 79 tested.

Anemia as a marker for overall micronutrient deficiency appears to be common in Syrian refugees. In 2014, an evaluation of anemia prevalence in the Zaatari refugee camp and outside environs showed that 48.4% of children under 5 years and 44.8% of women 15-49 years old suffered from anemia [34].

A 2012 study of nutrition of women and children in Jordanian refugee camps and those residing in urban and rural settings found that in refugee camps, 5.8% were suffering from wasting, and in urban settings, 5.1%. Moderate malnutrition was noted in 4% of children under 5 years and 6.3% of pregnant and nursing women and girls. Of note, under half of refugee camp and urban dwellers (49.6% and 42.7%, respectively) were still breast feeding children under 2 years of age [35]. An April 2014 study in the Jordanian Zaatari refugee camp and outside the camp showed relatively low rates of acute malnutrition in children 6-59 months (1.2% and 0.8% respectively), however, chronic malnutrition was more pronounced with 17% of children inside the camp and 9% outside the camp suffering from stunting [34].

In 2014, a study of refugees living in Jordan and Lebanon showed that 5.7% of refugees had significant injuries directly related to the Syrian conflict. One out of 15 and one out of 30 refugees had suffered war-related injuries in Jordan and Lebanon, respectively with 58% due to bombing, shrapnel and gunshot wounds and 25% from falls and burns [27].

In a 2012 evaluation of mental health needs in Syrian refugees camps in Turkey, 55% of refugees were determined to be in need of psychological management and almost 50% of refugees surveyed believed that they or family members needed psychological supports [36].

Pediatric mental health

In a study conducted in Islahiye Camp (Turkey), researchers found that Syrian refugee children had experienced very high levels of trauma. Of the children surveyed, 44% reported symptoms of depression, and 45% showed signs of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 10 times the prevalence among children worldwide [37].

Summary

Syrian refugees have only recently been resettled into the United States compared to many refugee groups, so some of their health concerns may not be well-known. The information provided in this refugee health profile is intended to help resettlement agencies, clinicians, and providers understand the cultural background and health issues of greatest interest/concern pertaining to resettling Syrian refugee populations. The following health conditions are considered priority health conditions when caring for or assisting Syrian refugees: hypertension, diabetes, and mental health. These health conditions represent a unique health burden for the Syrian refugee population, although this population may have other health conditions as well.

- Library of Congress, Country Profile: Syria. 2005.

- Rodgers L, et al. Syria: The story of the conflict. Oct. 2015; Available from: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-26116868.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2015 UNHCR country operations profile - Iraq. 2015; Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e486426.html.

- The World Bank. Syria. 2015 [cited 2015 November 23]; Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/syria.

- United States Census Bureau. Syria. 2015 [cited 2015 November 19]; Available from: http://www.census.gov/popclock/world/sy?cssp=SERP.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2015 UNHCR country operations profile-Syrian Arab Republic. 2015; Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e486a76.html.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Europe: Syrian Asylum Applications. 2015 [cited 2015 November 19]; Available from: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/asylum.php.

- CIA World Factbook. Syria. 2015; Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sy.html.

- Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Refugees from Syria. 2014.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Syria Crisis: Education Interrupted. 2013.

- Wehbe-Alamah H, The use of Culture Care Theory with Syrian Muslims in the mid-western United States. Online Journal of Cultural Competence in Nursing and Healthcare, 2011. 1(3).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Syria Regional Refugee Response 2015; Available from: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php.

- Zong, J. and J. Batalova, Middle Eastern and North African Immigrants in the United States. 2015, Migration Policy Institute.

- Ajrouch K, Pan Y, and Lubkemann S, Observing Census Enumeration of Non-English Speaking Households in the 2010 Census: Arabic Report, in Research Report Series. 2012, U.S. Census Bureau.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, At a glance: health data for Syrian refugees. 2014.

- Reese Masterson A, et al., Assessment of reproductive health and violence against women among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Women's Health, 2014. 14(1): p. 1-8.

- Doedens W, et al., Reproductive Health Services for Syrian Refugees in Zaatri Refugee Camp and Irbid City, Jordan. 2013.

- Samari G, The Response to Syrian Refugee Women’s Health Needs in Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan and Recommendations for Improved Practice, in Knowledge & Action, Humanity in Action. 2015, Humanity in Action, Inc.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Profile. [cited 2015 November 6]; Available from: https://extranet.who.int/sree/Reports?op=Replet&name=%2FWHO_HQ_Reports%2FG2%2FPROD%2FEXT%2FTBCountryProfile&ISO2=SY&LAN=EN&outtype=html.

- Cookson ST, et al., Impact of and response to increased tuberculosis prevalence among Syrian refugees compared with Jordanian tuberculosis prevalence: case study of a tuberculosis public health strategy. Confl Health, 2015. 9(18).

- Chemaitelly H, Chaabna K, and A.R. LJ., The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in the fertile crescent: Systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 10(8).

- Saroufim M, et al., Ongoing epidemic of cutaneous leishmaniasis among Syrian refugees, Lebanon. Emerg Infect Dis, 2014. 20(10): p. 1712-5.

- Alawieh, A., et al., Revisiting leishmaniasis in the time of war: the Syrian conflict and the Lebanese outbreak. Int J Infect Dis. , 2014. Dec;29:115-9.

- Inci R, et al., Effect of the Syrian Civil War on Prevalence of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Southeastern Anatolia, Turkey. Med Sci Monit, 2015. 20(21): p. 2100-4.

- Koçarslan S, et al., Clinical and histopathological characteristics of cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Sanliurfa City of Turkey including Syrian refugees. . Indian J Pathol Microbiol., 2013 56(3): p. 211-5.

- World Health Organization, Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles. 2014. http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/syr_en.pdf.

- de Leeuw L, The situation of older refugees and refugees with disabilities, injuries and chronic diseases in the Syrian Crisis. Handicap International 2014.

- Moukeh G, et al., Epidemiology of hemodialysis patients in Aleppo city. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 2009. 20(1): p. 140-146.

- Hamamy HA and Al-Allawi NAS, Epidemiological profile of common haemoglobinopathies in Arab countries. J Community Genet, 2013. 4(2): p. 147-167.

- El-Hazmi MAF, Al-Hazmi AM, and Warsy AS, Sickle cell disease in Middle East Arab countries. Indian J Med Res, 2011. 134(5): p. 597-610.

- Beutler E, Duparc S, and G6PD Deficiency Working Group, Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency and Antimalarial Drug Development. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg, 2007. 77(4), pp. 779–789.

- Ward KD, et al., The tobacco epidemic in Syria. Tob Control, 2006. 15(Supp 1): p. i24-i29.

- Mattit HH, Familial Mediterranean fever in the Syrian population: gene mutation frequencies, carrier rates and phenotype-genotype correlation. European journal of medical genetics, 2006. 49(6): p. 481-486.

- Bilukha OO, et al., Nutritional Status of Women and Child Refugees from Syria-Jordan, April–May 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 2014. 63(29): p. 638-9.

- Sebuliba H and El-Zubi F, Meeting Syrian refugee children and women nutritional needs in Jordan. 2014.

- Sahlool Z, Sankri-Tarbichi AG, and Kherallah M, Evaluation report of health care services at the Syrian refugee camps in Turkey. Avicenna J Med, 2012. 2(2): p. 25-8.

- Sirin, S.R. and L. Rogers-Sirin, The education and mental health needs of Syrian refugee children. 2015, Migration Policy Institute.