Contact Info

Ticks

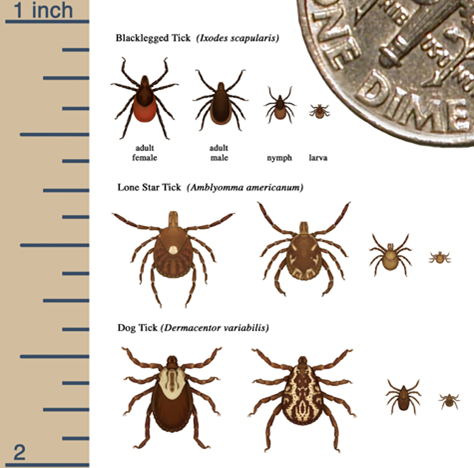

In Minnesota, there are about a dozen different types of ticks. Not all of them spread disease. Three types that people may come across in Minnesota are the blacklegged tick (aka deer tick), the American dog tick (aka wood tick), and the lone star tick. The blacklegged tick causes by far the most tickborne disease in Minnesota. People in Minnesota are often bitten by American dog ticks but they rarely spread diseases. American dog ticks may spread Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia. Lone star ticks are rarely found in Minnesota, but can spread diseases such as ehrlichiosis and tularemia.

The blacklegged tick, shown in the lower right, is much smaller than the American dog tick, shown in the upper right. The lone star tick is shown in the upper left of this photo and is a little smaller than the American dog tick but larger than the blacklegged tick

Blacklegged Tick Life Cycle

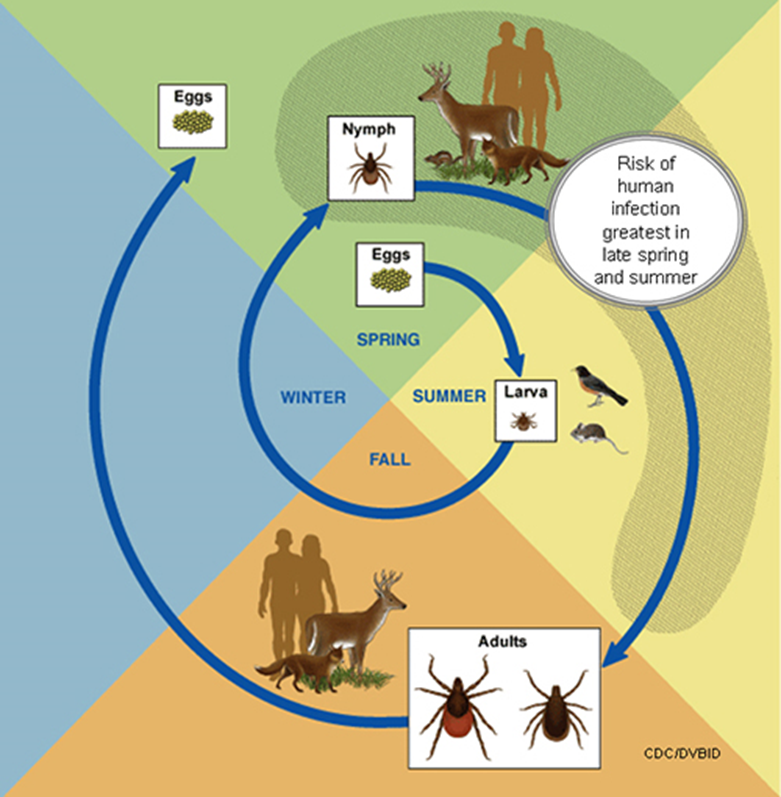

Blacklegged ticks live for about two to three years. Most of their life is spent out in the environment rather than on a host or in a host’s nest. During their entire lifetime, they will only have up to three blood meals. The picture below shows that the life cycle begins when the female lays eggs. As the egg matures, it develops into a larva (right-middle), then a nymph (top-middle) and finally, an adult male or female (bottom-right).

In the spring of their first year, eggs hatch into larvae. Larvae prefer to feed on blood from small mammals, like mice and birds. Larvae have one feeding then molt into nymphs and rest until the next spring. During this first meal, the larva may pick up a disease agent (like the bacteria that causes Lyme disease) while feeding on a small mammal, such as a white-footed mouse.

Late in the spring of their second year, nymphs take their second feeding. Nymphs aren’t as picky with their choice of host and will feed on blood from small or large mammals, such as white-tailed deer or humans. At this time, if the nymph is infected with a disease agent then it could spread the disease agent to a human or animal that it feeds on.

In the fall of their second year, nymphs that have had a blood meal will molt into an adult male or female tick. Adults prefer to feed on large mammals, such as white-tailed deer or humans. The females find a host to feed, mate with an adult male tick, lay hundreds to thousands of eggs, and then die. The males attach to a host to find a female mate and then die. Some adults who do not feed or mate in the fall will survive through the winter and then come out to feed and/or mate the following spring. If there is little to no snow cover and temperatures rise above freezing, it is possible to find an active adult tick searching for a host on a warm winter day.

In Minnesota, adult ticks will usually emerge right after the snow melts and reach peak spring-time activity during the month of May. The adult ticks will typically stay active throughout June. Adults will also become active again in the fall, usually by the end of September and through October, until temperatures drop below freezing or snow covers the ground. Blacklegged tick nymphs start to become active in mid-May and reach peak activity at the end of May through the month of June. Nymph activity tapers off slowly, and they are much less active by the end of July. Larvae are typically most active in June.

This picture shows each of the life stages of the blacklegged tick: adult female, adult male, nymph, and larva. It also shows the relative sizes and patterns of the blacklegged tick, lone star tick, and American dog tick.

Feeding and blood meals

- Blacklegged ticks feed on blood by inserting their mouth parts into the skin.

- They are slow feeders and will usually feed for 3-5 days.

- In order to spread disease to a human or animal, a tick needs to be infected with a disease agent and it needs to be attached to the host for a certain amount of time.

- If the blacklegged tick is infected, it must be attached for 24-48 hours before it transmits Lyme disease.

- Less common tickborne diseases, such as anaplasmosis, may take less time.

- On average, about 1 in 3 adult blacklegged ticks and 1 in 5 blacklegged tick nymphs is infected with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease.

NPR: WATCH: How a Tick Digs Its Hooks Into You

Watch this video from National Public Radio on how ticks latch on.

Blacklegged Tick Habitat

Where do we find blacklegged ticks?

- Blacklegged ticks live in wooded, brushy areas that provide food and cover for white-footed mice, deer and other mammals.

- This habitat also provides the humidity ticks need to survive.

- Exposure to ticks may be greatest in the woods (especially along trails) and the fringe area between the woods and border. Rarely, blacklegged ticks may be found in more open areas (such as yards) that are near wooded habitat so it is important to be on the lookout for ticks when in or near wooded areas.

- Blacklegged ticks search for a host from the tips of low-lying vegetation and shrubs, not from trees.

- Generally, ticks attach to a person or animal near ground level.

- Blacklegged ticks crawl; they do not jump or fly. They grab onto people or animals that brush against vegetation, and then they crawl upwards to find a place to bite.

- White-tailed deer live throughout Minnesota, but blacklegged ticks are not found everywhere that deer live.

Tick Photos

Blacklegged ticks thrive in wooded and brushy habitat like this. Try to stay on the mowed trail while walking through here in order to reduce your risk of tick bites.

Blacklegged ticks spend most of their life on the ground, under the leaf litter layer of the forest. This is an adult female blacklegged tick that we found in her usual habitat.

This adult female blacklegged tick can be identified by the reddish-orange coloring on her back. We caught her “questing”, a behavior by which the tick holds out its two front legs and waits for an animal or person to brush by so that it can grab onto a host.

Look how small this blacklegged tick nymph is compared to the thumbnail. We found it on a drag cloth while we were collecting ticks out in the woods.

Can you find the tiny blacklegged tick larva near the knuckle of this hand? Larvae are the smallest life stage of tick that develop from eggs.

These ticks have been lined up next to the thumb so you can see their relative sizes. From left to right are the blacklegged tick (deer tick) larva, nymph, adult male, and adult female followed by the American dog tick (wood tick) adult female and adult male.

After ticks are collected out in the field, they are brought back to the office for identification under the microscope. This picture focuses on a blacklegged tick nymph – its large mouthparts are important for biting and staying attached to a host for the entire feeding period, which usually lasts 3-5 days.

Here is an adult female blacklegged tick on a thumb. Adult blacklegged ticks are about the size of a sesame seed.

Here is an adult female blacklegged tick on a thumb. Adult blacklegged ticks are about the size of a sesame seed.

This picture shows a blacklegged tick nymph near a fingernail. Nymphs are smaller than adult ticks and are about the size of a poppy seed.

This MDH staff person is dressed in white to more easily spot ticks that may grab and crawl onto them while out in the woods. He is pointing to two adult female blacklegged ticks (left) and one male blacklegged tick (right) on his pant leg.

CDC: What to Do After a Tick Bite

A selection of resources showing life cycles, proper tick removal, bite prevention, illustrations of how to do a proper tick check and more.