Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Waterline: Fall 2018

Editor:

Stew Thornley

Subscribe to The Waterline newsletter. An e-mail notice is sent out each quarter when a new edition is posted to the web site.

On this page:

- Water Bar at Capitol a Highlight of Safe Drinking Water Week

- The Poop Scoop

- Get the Exam Prep App

- Minnesota AWWA Promotes Science, Technology, Engineering, Math (STEM)

- Clean Water Fund Success Story: Rock County Rural Water District

- A Look at the Other End

- Fluoridation Rule Revision

- MDH Publishes Fact Sheet on Home Water Softening

- Water on Its Way to Worthington

- DWP Profile: Barb Moore

- New Toolkit Will Help You Communicate

- Reminder to All Water Operators

- Calendar

Water Bar at Capitol a Highlight of Safe Drinking Water Week

|

Governor Mark Dayton proclaimed May 6-12 Safe Drinking Water Week in Minnesota. As part of a week of activities, Water Bar was at the capitol and staffed by members of the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) Drinking Water Protection Section on Wednesday, May 9. The watertenders served cups of water from St. Paul, St. Peter, and White Bear Township. MDH Commissioner Jan Malcolm spoke at the event, as did Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Commissioner John Linc Stine, Minnesota Section of the American Water Works Association (AWWA) Chair Dave Brown, and Minnesota Rural Water Association Executive Director Lori Blair. |

|

Go to top

The Poop Scoop

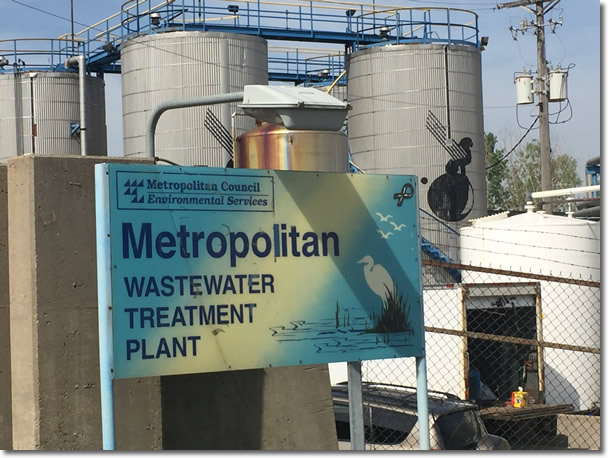

The Twin Cities seven-county metro area contains more than 150 community water supply systems, but the same area is served by only eight wastewater plants. The largest is the Metro Plant, downriver from downtown St. Paul. It treats an average of 172 million gallons of wastewater per day. Nearly 400 miles of interceptor pipes bring the majority of the Twin Cities’ wastewater to the plant.

Go to topGet the Exam Prep App

American Water Works Association (AWWA) has developed an app for smartphones and web browsers that contains practice questions for those studying to take a certification exam. An app with 100 questions in four subject areas is free, and additional questions are available for purchase. In addition, the app can be purchased with a Water Operator Certification Exam Prep book that has more than 1,400 questions and answers.

Go to top

Minnesota AWWA Promotes Science, Technology, Engineering, Math (STEM)

By Carol Kaszynski

City of Bloomington and Chair of the Minnesota American Water Works Association Training and Education Council

The Science Technology Engineering Math (STEM) Committee has been busy. The focus is that we are the ambassadors of the water industry, a philosophy that includes being a role model, showing enthusiasm relating to all areas of the industry, and generating conversations regarding the industry with young, middle-aged, and older people.

The Science Technology Engineering Math (STEM) Committee has been busy. The focus is that we are the ambassadors of the water industry, a philosophy that includes being a role model, showing enthusiasm relating to all areas of the industry, and generating conversations regarding the industry with young, middle-aged, and older people.

Our infrastructure assets are aging, as is another previous asset – our staff. As members of the Minnesota Section, we are all ambassadors of the industry. The STEM committee believes it is our mission to recruit, develop, and retain people from all backgrounds and diversity to provide safe and reliable utility services to our customers.

The STEM committee developed material for cities, other government agencies, consulting firms, and vendors to share with potential recruits. The material includes information regarding job descriptions, career benefits, useful web links, and hands-on exercises.

The material can be distributed when given the opportunity to perform outreach services at such events as city open houses, remodeling fairs, community concerts, fun run/walks, and farmer’s markets.

Along with printed material, the committee purchased STEM items that can be given to attendees. There are three STEM banners and signs to be incorporated into your display. These items are all free to the Minnesota AWWA members.

Additionally, the STEM committee is developing a web page that will include testimonials from industry professionals. Short videos and photos of Minnesota AWWA members will promote the water industry. All of the developed material is available to MN AWWA members.

There are 10 pilot agencies that will be testing the material. If interested in participating with the testing or would like materials, please contact me, Carol Kaszynski, ckaszynski@bloomingtonmn.gov, 952-563-4848.

Go to top

Clean Water Fund Success Story

Rock County Rural Water District

By Anna Arkin, Minnesota Department of Health

Rock County Rural Water District (RCRW) serves just over 3,000 people in southwest Minnesota. Unlike much of the state, southwest Minnesota does not have abundant water. Much of the surface waters are impaired, and groundwater resources are scarce. This concern is heightened for RCRW because water quality monitoring has shown that nitrate contamination exists, which is a significant public health concern. This relative scarcity and lack of good alternatives has led RCRW to recognize the importance of proactive source water protection.

Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) staff helped RCRW develop an action plan for protecting local sources of drinking water. As a result of the plan, RCRW built relationships with local landowners to educate them about options for managing their land to protect source water. RCRW then worked with farmers and provided financial incentives to implement nitrogen Best Management Practices on about 1,700 acres of land. MDH helped make these activities possible through Clean Water Fund-supported grants.

The Clean Water Fund supports this combination of MDH technical and financial assistance with hundreds of public water systems across the state. This assistance is crucial to the success of source water protection work. Many public water systems are small communities that lack the resources to be able to conduct the work on their own. These efforts protect drinking water for millions of Minnesotans.

For its effective implementation of its source water protection plan, along with the meaningful planning process used for the implementation, Rock County Rural Water District received the American Water Works Association (AWWA) 2018 Exemplary Source Water Protection Award for Small Source Water Systems at the AWWA Annual Conference & Exposition in Las Vegas. “This is a great honor, and we are proud to receive this award,” said Joey Pick (pictured below) of Rock County Rural Water at the convention.

“AWWA has a formal methodology for communities to use in source water protection, and our wellhead protection framework fits right into that,” said Steve Robertson, head of the MDH Source Water Protection Unit. “In the end, though, the system itself demonstrated the leadership to carry out their source water protection work with a high degree of integrity and determination, and I am very glad they have gotten this recognition.”

Go to top

A Look at the Other End

We Focus on Water Supply. What Happens Next?

Most of the articles in the Waterline focus on water supply and making the water safe to drink; the other end of the process is just as important, and recently employees of the Minnesota Department of Health had the chance to tour the Metropolitan Wastewater Treatment Plant. To accompany the photos and description of the plant is a story, “Clear Water Obsession,” that was written by the editor of the Waterline more than 25 years ago, when he was a reporter for Construction Bulletin magazine. This story appeared in a special anniversary issue, Construction Bulletin: The First 100 Years:

Most of the articles in the Waterline focus on water supply and making the water safe to drink; the other end of the process is just as important, and recently employees of the Minnesota Department of Health had the chance to tour the Metropolitan Wastewater Treatment Plant. To accompany the photos and description of the plant is a story, “Clear Water Obsession,” that was written by the editor of the Waterline more than 25 years ago, when he was a reporter for Construction Bulletin magazine. This story appeared in a special anniversary issue, Construction Bulletin: The First 100 Years:

It wasn’t that long ago that a stroll along the Mississippi River produced an unsightly sight: raw sewage, huge mats of it floating downstream like a dead turtle.

For years, residents relied on the Mississippi to ingest whatever they put into it, using its natural biological abilities to process and assimilate the foreign materials. In this, they hardly differed from other cities in the United States located adjacent to major waterways. Rivers, lakes, oceans, and other bodies of water can be remarkably proficient in purifying waste. The large quantity of clean water diluted the sewage; the natural movement of the water carried the sewage away from the cities; and naturally occurring microorganisms in the water consumed organic wastes.

But, as was the case elsewhere, the problems of turning a river or lake into an open sewer of human and industrial waste eventually took its toll. As the water became murkier, recognition of the hazards became clearer.

Locally, the health implications with the lack of adequate sanitation became cause for concern as far back as the mid-1800s. Although sewers began to replace backyard-disposal practices in the 1870s, the sewage still ended up in the same place: the Mississippi River.

Somehow people were still able to ignore the brown and oily texture the river was taking on as it began to live up to one of its many nicknames: the “Big Muddy.” Spring floods were the savoir as the flushing action of the high water scoured the banks of the Mississippi, removing the past year’s deposits of sludge and providing an adequate amount of natural cleansing.

But the opening of the Ford Dam in 1917 slowed the current of the water above the dam, reducing the purging action of the spring flooding. Sludge deposits quickly formed, and by dawn of the Roaring Twenties, an estimated three million cubic yards of sewage sludge was settling—much of it clearly visible on the surface—in the waters upstream from the dam. No longer could residents close their eyes—or their noses—to the fouling of their waters.

Once again, health concerns were the catalyst for action. The Minnesota State Board of Health proclaimed the Mississippi River a “public-health nuisance,” prompting the appointment of a drainage commission and the eventual formation of the Minneapolis-St. Paul Sanitary District in 1933.

Two years later, work began on a wastewater treatment plant on Pig’s Eye Island, a few miles downstream from downtown St. Paul. With the completion of the Pig’s Eye Plant in 1938, the Twin Cities became the first major metropolitan area along the Mississippi River to treat its sewage before dumping it into the water. Its effects were immediate and dramatic. The floating rolls of sewage virtually disappeared, and levels of dissolved oxygen, a critical water quality indicator, rapidly improved. From a health standpoint, the implications of the treatment were also readily noticeable.

The Pig’s Eye Plant was hailed as an engineering marvel and attracted thousands of visitors to tour the facility. Many were engineers from other parts of the country, hoping to learn the secrets of the Pig’s Eye processing as they planned similar practices for their community.

The art-deco administration building (above) was part of the original Pig’s Eye Plant, which now covers more than 100 acres (below).

As the region continued to grow, more treatment plants were necessary. Today, the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area has 11 such plants, all under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Waste Control Commission (MWWC), established by the Minnesota Legislature in 1969.

The original Pig’s Eye Plant has hardly been overshadowed by the addition of others. Although it has been renamed (now called simply the “Metro Plant”), it remains the largest wastewater treatment facility serving the Twin Cities. It treats 225 million gallons of wastewater per day, about half the wastewater generated in the state and 80 percent of that by the Twin Cities. The combined residential-industrial-commercial population served by the plant is more than two million people.

The treatment process at the Metro plant essentially mimics the natural ability of the water to cleanse itself as some particles are removed through sedimentation and others are ingested by microbes, although at a greatly accelerated rate.

The first process takes place in primary treatment. Sand, grit, and the larger solids in the wastewater are separated from the liquid through the use of screens, settling tanks, and skimming devices. Approximately half of the pollutants are removed in this phase.

Following primary treatment, a biological process takes place to remove most of the remaining pollutants. Air is infused in the wastewater to stimulate the growth of microbes—bacteria and other organisms—that then consume the waste materials. In the process, ammonia is also converted into non-toxic nitrates.

The water is then separated from the organisms and solids, which settle to the bottom of the separation tanks, where it is either incinerated, placed in landfills, or used as a soil conditioner in agricultural areas. At some treatment plants, this sludge serves as a fuel to produce energy.

The water is disinfected with chlorine—which is later neutralized to keep it from harming aquatic life—to kill any harmful bacteria that remain and, finally, released into the Mississippi River.

The Metro Plant is a gravity-fed treatment system. The progressive phases are slightly lower in elevation than the previous ones, allowing water to pass through the plant and finally into the river without the need for pumps.

In addition to the treatment plants, the MWWC owns and maintains 500 miles of interceptor sewer pipes (sewers that intercept the flow of the original city sewers) that carry sewage from the producers to the treatment facilities.

Construction on the Minneapolis East Interceptor, 40 feet below northeast Minneapolis. The largest tunneling project in Minnesota up to that time, the interceptor was completed in 1991.

The sewers have been the focus of increasing attention in recent years. When the city sewers were first built late in the 19th century, they were designed to carry both storm water and sewage to the river. The interceptor sewers, however, are designed to handle only normal sewage flows. Heavy rains or rapid snow melts can increase the flow in the city sewers to the point that some of the combined flow—run-off and wastewater—bypasses the interceptor sewers and flows directly into the river.

In 1984, it was estimated that 4.6 billion gallons of combined untreated sewage and stormwater flowed into the Mississippi annually.

The cities of Minneapolis, St. Paul, and South St. Paul began work to provide separate storm and sanitary sewers. Their initial schedule did not call for complete separation until 2025. In 1985, however, the Minnesota Legislature mandated an accelerated 10-year schedule for the three cities, with total separation of the sewers finished by the end of 1995.

Although treatment practices of some type have been in existence for many years, it has been only in the last quarter-century that national standards on water quality have been set. Because of the leading role Minnesota has taken with regard to wastewater treatment, the MWWC has had no trouble in adhering to contaminant limits established with the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972 and subsequent amendments to the Act.

Construction never ceases on the MWCC’s system of plants and sewers. Flood protection projects completed in 1975 provided for an earthen dike and concrete floodwall to an elevation nearly eight feet above the water levels during the record floods of 1965. An effluent pumping station was added in 1977. These improvements paid dividends in June of 1993 following periods of heavy rains. As the swollen Mississippi covered surrounding lowlands, including the downtown St. Paul airport, the Metro Plant continued operations to treat sewage.

The enhanced quality of water manifested itself in a strange way a few years ago. On a warm evening in June of 1987, a bumper crop of mayflies hatched in the Mississippi River near the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport. Attracted by the lights from nearby traffic, they converged on a bridge over the river, leaving Interstate 494 more than a foot deep in insects. The highway had to be closed and snowplows called out to clear the mayflies.

The good news in the story was that mayflies are signs of clean water. Despite the inconvenience they caused, their spawning was evidence that the state of the Mississippi River has indeed come a long way.

Go to top

Fluoridation Rule Revision

The Minnesota Department of Health Drinking Water Protection Section has begun revision of the portion of the state fluoridation rule that specifies the minimum, maximum, and average fluoride concentrations required at municipal public water systems. The original Request for Comment was published in the July 3, 2017 State Register (PDF).

The proposed revised language is:

Subp. 2. Fluoride content. The fluoride content of the water shall be controlled to maintain an average concentration of 1.2 0.7 milligrams per liter; the concentration shall be neither less than 0.9 0.5 milligrams per liter nor more than 1.5 0.9 milligrams per liter.

Some readers may have concerns, questions, or comments about the impacts of changing the lowest, highest, and target fluoride targets. Please visit the Minnesota Fluoridation Rule Revision web page for further information about the proposed rule revision, instructions for comment submission, and other relevant details.

Go to top

MDH Publishes Fact Sheet on Home Water Softening

The Minnesota Department of Health has a fact sheet that water utilities may share with their customers.

The fact sheet covers the basics of hard water and the softening process, provides a list of advantages and disadvantages of home water softening, and examines the health effects and environmental impacts of softening.

The fact sheet is available on the web at:

Home Water Softening: Frequently Asked Questions

Go to top

Water on Its Way to Worthington

|

Work continues on a meter building in Worthington and installation of 14-inch PVC pipe between Worthington and Adrian as part of the Lewis & Clark Rural Water System. Conceived in 1988 as a way of serving water-challenged areas in South Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota, the Lewis & Clark project takes water from a series of wells that tap into an aquifer adjacent to the Missouri River near Vermillion, South Dakota. The water is delivered to communities as far away as 125 miles. The water first reached Minnesota in 2015, reaching Rock County Rural Water District and is expected to reach Worthington by the end of 2018. |

|

Go to top

DWP Profile: Barb Moore

Barb Moore (left) and Sweet Moon

Barbara Moore has joined the Drinking Water Protection (DWP) Section of the Minnesota Department of Health as a management analyst in the St. Paul office. She will be involved in DWP data management and quality assurance activities, the Exchange Network Grant projects, and projects related to Minnesota Drinking Water Information System re-design/modernization.

Barb grew up in Minnesota but has spent the past 14 years out west, competing in rodeos and living on ranches. She has worked as a project manager for a college curriculum management software company as well as for the University of Colorado and the College of Eastern Idaho. She is nearing completion of a master's degree in organizational management.

Barb is single with no kids, and she has 5 nieces and/or nephews, 3 horses, and 1 dog. She is active with her horses, competing in barrel racing and breakaway roping. “I grew up on a horse,” she says, “and train my own horses. I also love to snowboard and love to cook.

“I look forward to meeting new people and will do my best in implementing the data management needs within DWP.”

Go to top

New Toolkit Will Help You Communicate

Have you ever had a customer ask, “Is my water safe to drink?” How about, “Why does my water have an odor/color?” When you answer these questions, you are engaging in risk communication. Risk communication is a science-based approach to informing people about potential hazards to their person, property, or community. More simply, risk communication is about giving people the right information at the right time to help them make decisions.

In a more connected and digital world, water professionals are expected to communicate faster and more frequently with stakeholders, including elected officials, customers, and partners. Increased communication presents an opportunity to build relationships, shape your message about drinking water, and engage audiences in ways that gain support for your public water supply and drinking water investments. It also presents challenges. How do you know you’re saying the right thing, in the right way?

Luckily, there are resources to help you communicate effectively. The new Minnesota Department of Health Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit contains strategies, examples, and templates to help you communicate about drinking water. The toolkit includes:

- Information about different types of communication, from teaching customers about your everyday operations to communicating about contaminants in drinking water.

- Strategies, examples, and templates for communications planning, making your message, and telling your story.

Use the toolkit to learn how to:

- Create simple-to-use, accurate, and clear messages about drinking water.

- Develop consistent messages to maintain and build confidence in tap water.

- Identify effective methods for communicating about contaminants in drinking water.

- Share examples of your communications successes with other public water systems.

- Request example messages on challenging or hot topics from MDH.

One of the duties of water professionals is to provide information about drinking water, especially about drinking water contaminants. We must convey information about potential health risks of exposure to contaminants (when applicable) and actions that can be taken to reduce exposure—while at the same time maintaining confidence in public water supplies.

Access the MDH Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit today to strengthen your communication skills. You can communicate with confidence at any time, in any situation.

Go to top

Reminder to All Water Operators

When submitting water samples for analyses, remember to do the following:

- Take coliform samples on the distribution system, not at the wells or entry points.

- Write the Date Collected, Time Collected, and Collector’s Name on the lab form.

- Attach the label to each bottle (do not attach labels to the lab form).

- Include laboratory request forms with submitted samples.

- Do not use a rollerball or gel pen (the ink may run).

- Consult your monitoring plan(s) prior to collecting required compliance samples.

Notify your Minnesota Department of Health district engineer of any changes to your systems.

If you have questions, call the Minnesota Department of Health contact on the back of all sample instruction forms.

Calendar

Operator training sponsored by the Minnesota Department of Health and the Minnesota AWWA will be held in several locations this spring.

Register for schools and pay on-line:

Go to top