Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Historic St. Paul Ballpark Leads to Information on Early Water Supply in City

From the Winter 2018-2019 Waterline

Quarterly newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

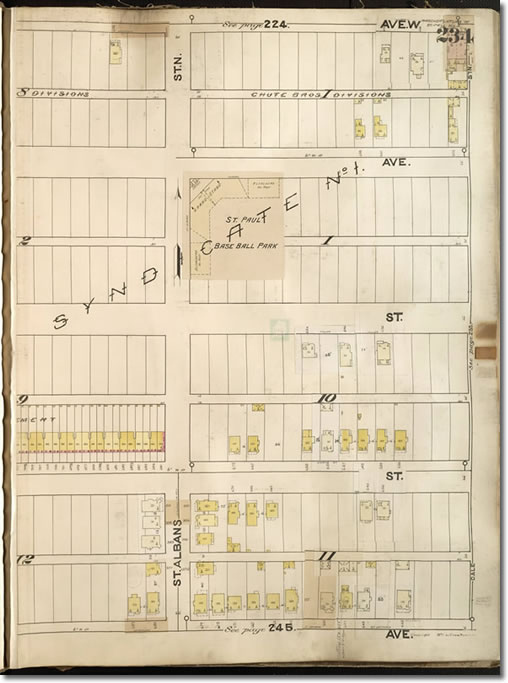

Researcher Cary Smith of the Baseball Hall of Fame came up with this map showing an 1890s baseball park in St. Paul.

Cary Smith, a Minnesota native who works at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, discovered that an 1895 ballpark built in St. Paul had showers installed. “I am trying to figure out if by 1895 that was a common thing or a relatively new and high-tech thing,” he asked.

The ballpark was on the northwest corner of Aurora Avenue, one block south of University Avenue, and St. Albans Street, one block west of Dale Street. Fuller Avenue is to the south.

Known as the Dale and Aurora Grounds, the ballpark was built for a new St. Paul minor-league team—owned and managed by Charles Comiskey—that played in the Western League. A few years later the Western League changed its name to the American League and became a major league. However, after the 1899 season, Comiskey moved the St. Paul team to Chicago. The team still exists, as the Chicago White Sox, and Comiskey is a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Ben Feldman, a project engineer for St. Paul Regional Water Services, looked into the water history of the area and got drawn into a mystery that required gumshoe work worthy of Hercule Poirot, Sherlock Holmes, or even Jim Rockford.

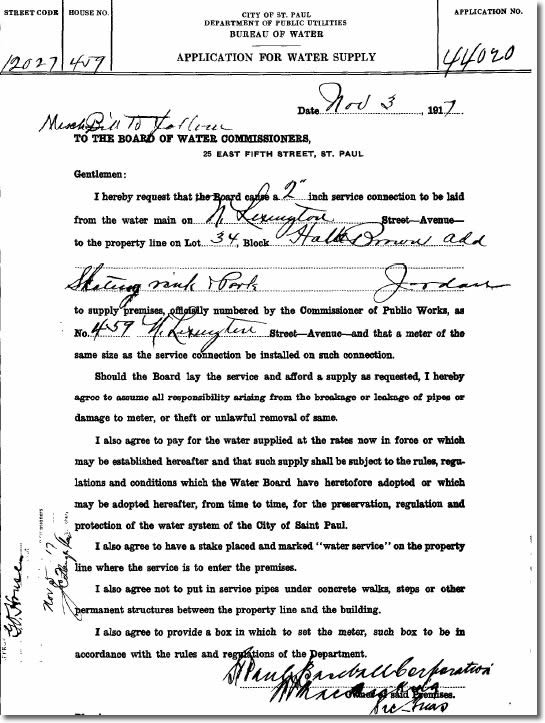

Ben Feldman of St. Paul Regional Water Services found this 1895 water permit for the ballpark, signed by John Comiskey, the dad of Charles, who supervised some of the construction.

Feldman found that a water main was installed for Aurora Avenue in 1889 and first thought that the city would have brought the service from near the intersection of St. Albans and Aurora to the grandstand of the ballpark.

However, he could find no record of old services in that location. “There are some abandoned services to the east of the intersection that had potential, but the one closest to the ballpark wasn’t installed until 1921. 1899 is the oldest date of those services, but they don’t quite coincide with the stadium construction date. The 1899 dates are not known for sure, but they all indicated having served the north side of Aurora. Again, not likely the stadium service. There doesn’t appear to ever have been a main installed in St. Albans and remains that way today.”

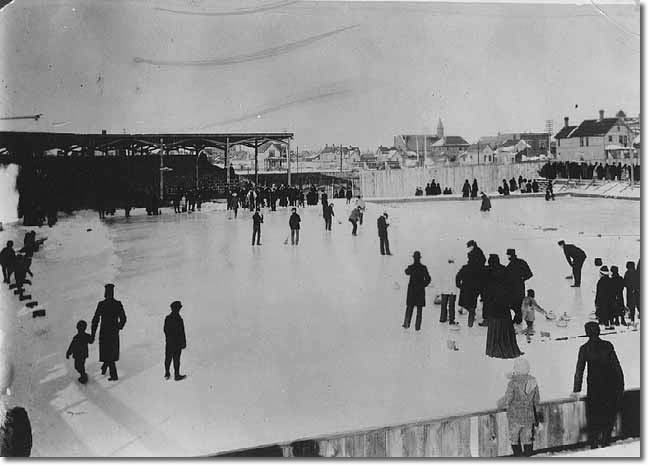

Feldman referred to a 2004 on-line article (Twin Cities Ballparks) that included a photo of the ballpark being used for curling. “The entire field was flooded, which means they had to be getting water from somewhere. Either they were getting it from a hydrant, a service, or a well. Given there was main in the street at the time, it wouldn’t make sense to have drilled a well. There are only two hydrants nearby—one at the intersection of St. Albans and Aurora and one at St. Albans and Fuller. It didn’t make sense to be dragging a hose across the street on Aurora, so it got me wondering if they were using the Fuller hydrant or possibly had a service off of Fuller.”

The photo above (courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society), of a flooded Dale and Aurora Grounds, led Ben Feldman to the answer of where the water came from.

Below: The water service that supplied the 1890s ballpark is still being used for a duplex on the corner of Fuller and St. Albans.

Feldman found that the main on Fuller was installed in 1891. “There are only two services on Fuller installed prior to 1900. One in 1891 to a house mid-block on the south side and one in 1895 right next to the hydrant at St. Albans and Fuller.”

On top of it all, this service is still being used today by a corner duplex now on the site. “It looks like we have quite a few services in the old neighborhoods that date back to the 1880s. Whether or not you had running water in your home at the time probably had more to do with your financial ability and if the city had the infrastructure in place,” Feldman concluded.

Once started on the history of water supply and St. Paul ballparks, Ben Feldman kept digging and found the original permit for water at Lexington Park, used by the St. Paul Saints from 1897 to 1956. The water installation date was December 10, 1917.

This 1952 photo of Lexington Park, looking to the southeast, shows University Avenue near the bottom (parallel to the third-base line) and Lexington Parkway beyond the left-field fence. A White Castle now stands at the corner of University and Lexington. Feldman says the location of the service was approximately at what is now the south edge of the White Castle driveway off of Lexington Parkway. Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Go to top