Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Gary Englund Remembers

Longtime Section Manager Tells It Like It Was

From the Fall 2024 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

Gary Englund (left) accepts an award in 2000 from John Baerg, director for National Rural Water Association (center), in recognition of Minnesota’s ranking as the top state in the nation in drinking-water compliance. At the right is MDH deputy commissioner Julie Brunner accepting the award for Minnesota having the top health rates in the country.

During the year-long celebration of the 50th anniversary of the federal Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), a pioneer in the development of the drinking-water program in Minnesota shared his memories. Gary Englund’s career at the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) pre-dates the SDWA, and he served as the manager of the Section of Drinking Water Protection (which has had several different names) for more than 30 years.

Born in 1947, Englund was a multi-sport athlete at Gladstone High School on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He spent much of his time hunting and fishing at the family farm and developed a life-long love of the outdoors. “I was in the woods hunting and fishing when I was seven years old.”

Englund thought he would go into the army after high school but was directed by his dad to attend Michigan Tech University in Houghton. While he thought his outdoor interests might lead to a major in forestry, Dad once again stepped in and recommended engineering. As for the specific field, Englund picked civil engineering for no other reason than his best friend had chosen it.

Upon graduation, he was recruited by several state agencies in Minnesota, including the highway department, now the Minnesota Department of Transportation, but he was more interested in an environmental field and accepted an offer to work at MDH.

“I just liked being around water,” he explained. “I like to fish. I like to be around rivers. I like to be around streams. I just had a love for being around water. I love to fish. Originally, I wanted to work for DNR [Department of Natural Resources], but DNR didn’t have the kind of job for me. So the only job that I had available to me was I could either go to PCA [Pollution Control Agency] or I could go to the health department. And I went to the health department because I think I had more of an advantage there.”

As a staff engineer in a program with few staff at the time, Englund “did everything.” He wrote the codes for swimming pools, plumbing, wells, and just about anything else related to water. Fluoridation became an issue as the state required mandatory fluoridation of drinking water. He wasn’t involved in the politics of it but recalls the battle over the resistance by the city of Brainerd.

“We went to court with Brainerd, and Brainerd was going to have a situation where they were going to share the penalty with their board, and it was a misdemeanor, so it was 90 days in jail and a fine. And so they thought that they would take turns serving the 90 days in jail, and the judge said, ‘Wait a minute. A violation occurs every day.’ So every day they didn’t [fluoridate], it was 90 days in jail and a fine. So they finally decided they would start the fluoridation equipment. They put a tap on the outside of the building that didn’t have fluoride for people that didn’t want to put fluoride in their water, and hardly anybody ever used it.”

Englund performed plan review on the installation of fluoride systems. “We required a special kind of installation that had a break box, and you double pump. So if you siphon, if we’re going to siphon fluoride into the system, you’d only siphon a cup. That was a maximum you could siphon. You couldn’t siphon a whole 55-gallon drum or the whole 50 gallon barrel or whatever it was. We had a couple of incidents where we had some overfeeds. One was, I can’t remember where the heck it was. Can’t remember right now, but we only had one or two.

“Minnesota’s got over 50 years of history with fluoridation. And if you talk to the dentists, they were really happy because it really reduced the dental caries in children.”

Transition with Passage of SDWA

Prior to the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act, the drinking-water program ran on money from the state general fund as well as a fee program for plan review, which allowed them to hire a full-time person to perform this work. The SDWA eventually brought in federal money.

Englund became the section manager at this time and worked on achieving primacy, which allowed the state to take over the administration and enforcement of the SDWA from the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In essence, the Minnesota Department of Health became a subcontractor of the EPA, doing the federal agency’s work in Minnesota. “We were the first state in [EPA] Region Five to get primacy and probably the fifth state nationally,” said Englund, who credits Pauline Bouchard (who eventually became head of the Public Health Laboratory at MDH) of his staff for writing the grant to EPA. “We got it [primacy] because of her, because she could work full time on it. I didn’t have the time.”

Additional hires who became stalwarts were Bruce Olsen, who led source water protection initiatives; Gunilla Montgomery, who handled training necessary for water operators to become certified; Dick Clark and Doug Mandy, who oversaw the public water systems; and Dan Wilson, who managed the private-well program, which eventually became its own section.

However, the growth took time and relied on money available. “The first grant [from EPA] was only 10,000 dollars, so we didn’t have a lot of staff at that time. I only had one district engineer and a couple of sanitarians, and then I hired three more district engineers to do two districts, and then I hired a district engineer for every district, and then I created a hierarchy because you need to have a place for people to grow if they’re going to stay.”

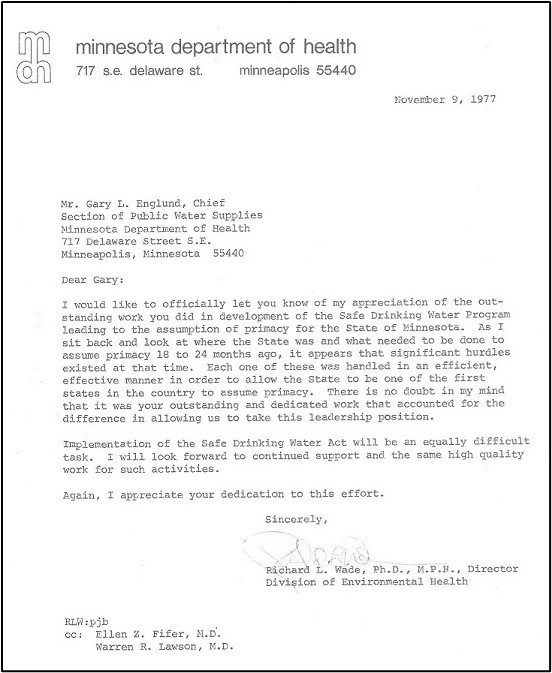

A letter to Gary Englund from division director Dick Wade after Minnesota achieved primacy in 1977.

The Englund Way

Long-timers credit this hierarchy and Englund’s philosophy on leadership with the strength of the program in the ensuing decades. “I always tried to hire somebody that was smarter than me because if they were smarter than me, it was easier for me to do my job,” he said.

Many past and current employees speak of how well Englund stood up for his people. After he retired, he has often heard, “We wish you were back. You fought for us.”

Englund is also remembered for being a financial whiz, and he was sometimes called on to help other sections in the MDH Environmental Health Division with their finances. “It was just something [finances] that I had an interest in, and I knew how to handle money. I knew how to take the dollars. The state fiscal year ran on a July to July. The federal fiscal year ran October to October, so I knew in that July to October quarter how to manage the money, so I didn’t have any state money left over. I didn’t have any federal money left over, but I also always knew how much money I had left in my budget every month. So I never overspent and I never underspent.”

Another important funding source began in the early 1990s with the inception of a new fee program, this one for $5.21 for each service connection in the state. (The fee was later raised to $6.36 and is now $9.72.) Cities collected the money from their customers and passed it on to the state, which has used it to pay for the analysis of water samples.

Englund explained the benefits of the state paying for analysis, coordinating the work with the MDH Public Health Lab, and dealing with the challenges of irregular sampling schedules for utilities and for specific contaminants.

“We had some monthly, we had some quarterly, we had some annually, we had some every three years, we had some every six years. . . . If they [the lab] got to a point where they were saturated and we gave ‘em another 10% of the samples, they would hire somebody else to do 10% of the samples, and they had 90% of the time where they weren’t doing anything. That was not efficient for me.

“Pauline [Bouchard] was running the lab at that time, and I said, ‘Pauline, I need to strike a deal with you. I will provide you – where you have staff that don’t have a complete year’s worth of sampling – I will provide them with enough samples to remain proficient.’ By doing that, that reduced my cost to our lab by 25%. That was significant.

“So then I took the additional samples that I had, and I subcontracted with private laboratories, and if the private laboratories went out to get samples done for lead and copper, they would’ve had to pay $40. That’s what the other states were paying their labs for doing lead and copper. I got that work for $10 a sample because number one, they knew how many samples they were going to get. They knew when they were going to come, and they knew they were going to get paid. So what I did by doing the sampling and monitoring program is I reduced the cost to the consumer of the state of Minnesota by driving the analytical costs down. Because if the utilities would’ve sampled, they would’ve had to pass that on to the customer.”

Early on, Englund decided to focus more on monitoring and less on enforcement. “Enforcement is not cheap. It was cheaper for me to monitor and create goodwill with the utilities than it was to create an enforcement program and create ill will.

“If there was a problem and they exceeded an MCL [maximum contaminant level] and they had to give public notice, that was an enforcement activity. We said, ‘You have to give public notice. You have to do this. You have to do that. You have to provide treatment, you have to do, and if you don't do it, we will have to take an enforcement action.’

“We didn’t have very many enforcement actions because we didn’t have very many violations.”

The approach of focusing more on cooperation and technical assistance instead of heavy-handed enforcement, along with fees that allow the state to pay for sampling, are major reasons that Minnesota has been a national leader in compliance with the SDWA, Englund said.

Connections

When Englund started, the Minnesota Department of Health was at 717 Delaware Street in southeast Minneapolis, on the edge of the University of Minnesota campus. The location, where MDH was until 2005, was because of the bond between the health department and university. Englund noted that the drinking-water program worked closely with some of the people at the U of M’s Department of Civil Engineering.

The relationship of drinking water and health is why the program in Minnesota is under a health rather than environmental agency. Englund noted this is rare around the country and that he was able to resist an attempt to move drinking water from the health department to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

Partnerships are another factor in the success of ensuring safe drinking water in the state. Minnesota Rural Water Association has circuit riders and trainers work with systems in Greater Minnesota, and, at Englund’s behest, MDH employees have become heavily involved in American Water Works Association (AWWA). Englund led the way, serving as chair as AWWA’s North Central (now Minnesota) Section and as the section’s director at the association level from 1990 to 1993.

Englund retired in 2003 (the picture below shows him receiving a plaque of appreciation from MDH). He splits his time between a home in Stillwater, near his son and daughter and their families, and the family farm in the Upper Peninsula. In either location, he spends a lot of his time in the woods and on the water.

“I’m 77 now,” Englund said. He still hasn’t slowed down.