Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Freeborn and Hartland Collaborate for Shared Water System

From the Summer 2019 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

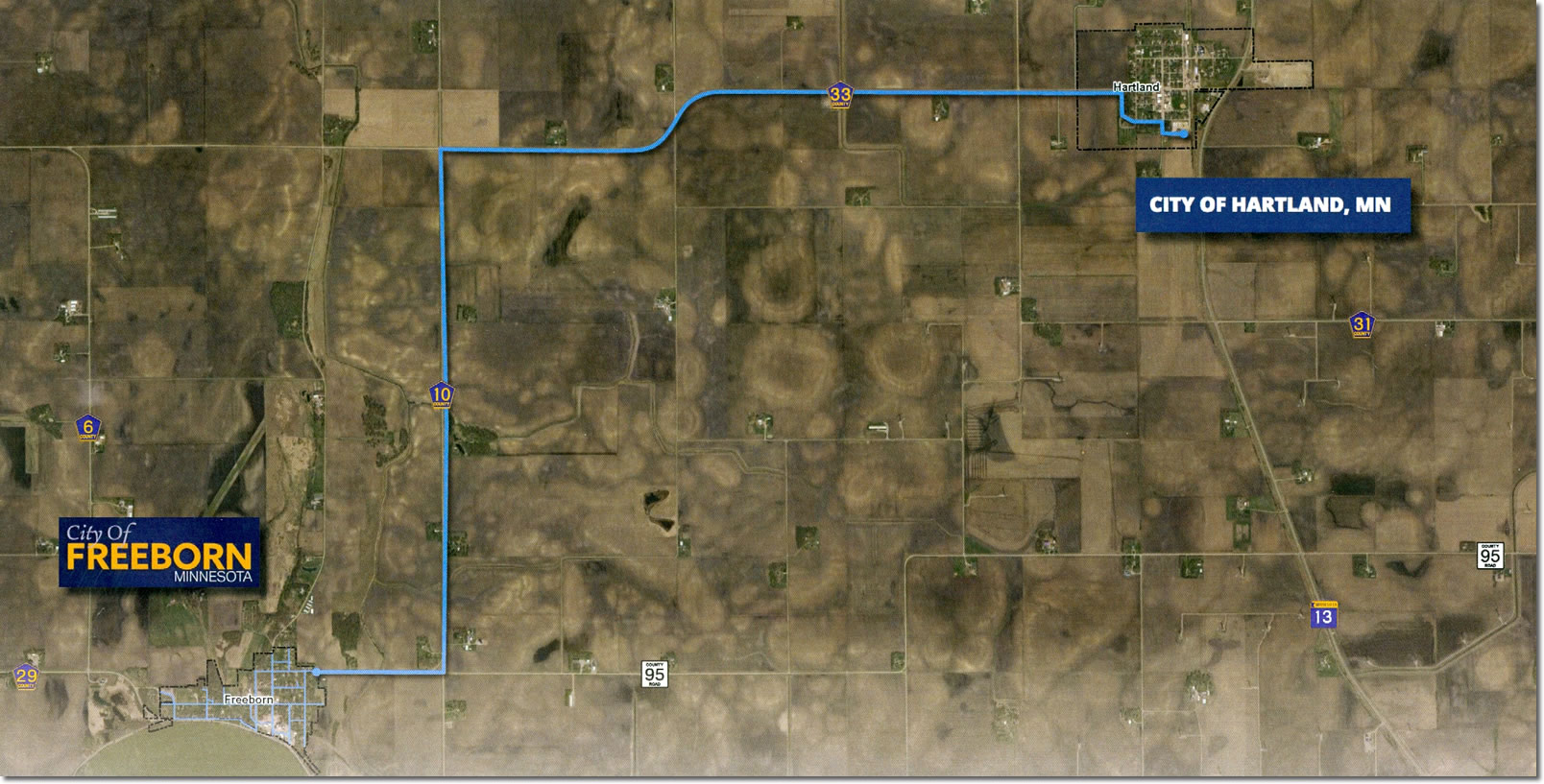

Two cities: one water plant. That’s how Freeborn and Hartland worked together to deal with separate water issues, save money, and serve their communities. (Click on the image above to enlarge it; click on it a second time to enlarge it even more.)

The southern Minnesota cities of Freeborn and Hartland are six miles apart and have faced different challenges with their drinking water, the former with arsenic and the latter with radium.

Hartland (home of humorist Al Batt) operated with a 1973 treatment plant that had never undergone any major renovations. According to Jake Pichelmann of Bolton & Menk, Inc. of Mankato, Minnesota, the chemical feed system was in poor condition, the electrical and controls equipment were obsolete, and the steel gravity filter leaked. Water/wastewater superintendent Andy Flatness said they used sandbags to direct water from the leaky filter to the floor drains. “The old plant was failing,” he said, “not pulling iron and manganese out like it should.” The plant was also not equipped to deal with rising radium levels.

Hartland’s 1959 well had sand issues and was being used as a backup, leaving only a 1992 well, which had corrosion and was in need of casing repairs.

Freeborn, which does not have a treatment plant, drew water from a pair of 1950s wells that were nearing the end of their life span. Its distribution system of 4-to-6 inch cast-iron pipe was in poor condition, and the city had experienced 12 main breaks within 5 years. “We needed to do something,” said water/wastewater superintendent Bill Guggisberg. Since it was exceeding the maximum contaminant level (MCL) for arsenic, the city had been operating with a compliance agreement with the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH).

|

||

| Bill Guggisberg and Andy Flatness stand next to a pipe that sends water to their cities—Freeborn to the left and Hartland to the right. | ||

|

Exploring a partnership, Guggisberg said they looked in different directions, including Alden to the south, and settled on Hartland, to the east. “It was a perfect fit—same size, same number of connections.” Guggisberg and Flatness had often worked together, helping one another’s cities with everything from street sweeping to putting up holiday lights.

Rather than build a new treatment plant itself, Freeborn participated in building a new treatment plant in Hartland, splitting the cost of the plant, which connected to both cities’ distribution systems. Hartland also added two new wells, which are arsenic-free, solving Freeborn’s problems.

The Hartland treatment plant has better aeration and detention to solve the city’s radium issues. As part of the project, Hartland replaced meters and mains and built a 75,000-gallon water tower.

“It was more cost-effective to hook up with Hartland,” explained Pichelmann. “The upside was that the incremental cost to increase the capacity wasn’t much—it was just making a 10-foot diameter gravity filter rather than an 8-to-9 foot diameter filter. The chemical feed didn’t change.”

The new Hartland plant is in front of the city’s water tower and next to the two new wells.

The plant has a packaged filtration unit that combines aeration, detention, and filtration. At the top is aeration, which strips the carbon dioxide and sulfide and oxidizes the iron. The chemical feed during detention includes potassium permanganate, a polymer, and chlorine as needed. The detention time of 30 minutes allows for proper reactions. A four-cell gravity filter at the bottom has 18 inches of greensand on top of 12 inches of anthracite.

Fluoride and chlorine gas provide dental protection and disinfection, respectively. The plant has a capacity of 150 gallons per minute. The economies of scale from two cities using one plant make for lower user costs, and the cities share the operation and maintenance costs proportionally.

Freeborn paid for the interconnection, 30,000 feet of six-inch PVC, as well as 20,000 feet of water mains in town. In addition, Freeborn replaced its meters. The pipeline from Hartland follows Freeborn County Hwy. 33 to the west and then south on Cty. 10 to Freeborn. “It follows the blacktop,” said Flatness, noting that using the main roads avoided the permitting problems they would have encountered had they taken a direct route, which would have involved going through land that had tiles and wind towers.

One of the reasons for placing the new plant in Hartland is because its elevation is about 18 to 20 feet higher than Freeborn, allowing gravity to aid the distribution. The plant has a booster pump, in case it is needed.

The preliminary engineering report for the project was completed in early 2012. The treatment plant was finished in 2013 and the interconnection in 2016.

The cities paid for the project with grants and loans from the Minnesota Drinking Water Revolving Loan Fund, the Public Facilities Authority, and the U. S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development. The total cost was $6,832,400.

The previous Hartland plant is two blocks north of the new one.

Freeborn is now in compliance with the arsenic MCL, and Hartland has alleviated its concerns with radium. In addition, the aesthetic quality of the water has improved as the new plant is effective in reducing iron and manganese. “The people are happy,” said Flatness. “They can get a glass of water with nothing floating in it.”

A joint water board from the two cities runs the system. One city has five members and the other four, with the cities switching that number around every two years.’

“It can be difficult for two communities to create a shared water supply,” said Karla Peterson of MDH, “but it’s encouraging to see when there is a success story.”

Guggisberg echoed Peterson’s sentiments and credited Bolton & Menk as well as MDH district engineer Paul Halvorson. “It was a lengthy process, but it was well worth it,”

“Everybody pitched in to get this job done. It’s basic, it’s simple, it works.”

Go to top