Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Kinney Secession: Effective but No Longer Necessary

From the Fall 2021 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

The 1996 amendments to the federal Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) created a revolving loan fund. Similar to one already in place for wastewater projects, the Drinking Water Revolving Fund (DWRF) provides below-market-rate loans to public water systems for capital improvements needed to achieve or maintain compliance with the SDWA. Since the inception of the DWRF, Minnesota has funded nearly 600 projects totaling more than $1 billion.

What was life like, especially for smaller communities, before DWRF? Cities had to get creative, and the saga of one Minnesota Iron Range town lives on nearly half-a-century later.

The Iron Range in Minnesota is associated with iron-ore mining districts in the northeast part of the state. The Vermilion Range wraps around the Ely area. The larger Mesabi (also spelled Mesaba and pronounced as such) Range—mostly to the southwest of the Vermilion—encompasses a region that includes Hibbing, Chisholm, Virginia, and Eveleth. Amid these cities have existed numerous “locations,” communities on the edge of an open mine pit that were established to provide residences for the workers and not meant to continue for longer than the mine was operational.

Early in the 20th century, a location emerged between Virginia and Chisholm, a mile north of what is now U. S. Hwy. 169. Known as Kinney (after O. D. Kinney, an early miner in the area), its population peaked at more than 1,200 and then declined; however, the city of Kinney lived on, even though its utilities weren’t intended to last for decades. A surge in residents—from 325 in 1970 to 600 by mid-decade with the expansion of a U. S. Steel mine—taxed its aging infrastructure.

Mary Anderson grew up in Kinney and, after excursions to other parts of the country, returned to her hometown and began operating a liquor store and bar with her dad in the 1940s. In the 1960s she became a nurse and worked at the hospital in nearby Virginia. She was also active in the Democratic-Farmer-Labor (DFL) party, an affiliate of the national Democratic party. The DFL at the time dominated the region, which has been historically aligned with organized labor. Paul Wellstone even kicked off the Iron Range portion of his 1990 U. S. Senate run at Mary’s Bar in Kinney and has called Anderson the “soul of the Iron Range.”

In 1973 Anderson took on another role: mayor of Kinney. Two years before she had run and narrowly lost to a man who then died in office. Anderson prevailed in a special election to fill the vacancy and was re-elected in 1975 with a pledge to get funding to improve the city’s water system. Beset with iron and manganese that fouled its aesthetic qualities, the water also had problems with built-up mineral deposits in the pipes. Anderson saw the effects when her family home, by this time a rental property, burned in 1974. Besides the issues with low pressure in the pipes, one of the fire hydrants didn’t work.

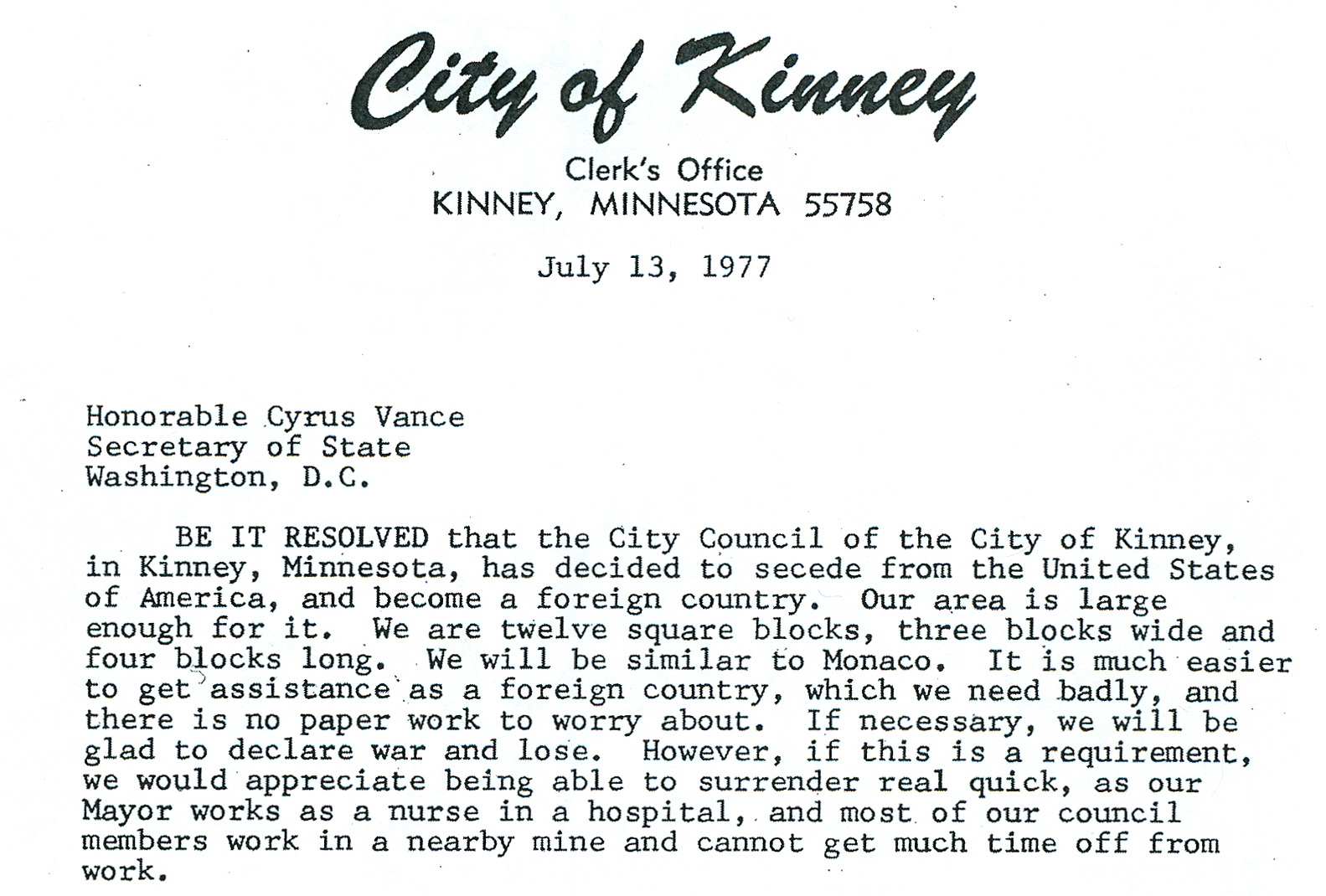

Anderson and the city council filed countless grant applications and searched for money, with little success. At a meeting on July 12, 1977, the group decided to follow on an idea that had come up in earlier brainstorming—secession. Village attorney Jim Randall was told to draft a letter to U. S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. The next day the city officials signed and sent the missive:

BE IT RESOLVED that the City Council of the City of Kinney, in Kinney, Minnesota, has decided to secede from the United States of America, and become a foreign country. Our area is large enough for it. We are twelve square blocks, three blocks wide and four blocks long. We will be similar to Monaco. It is much easier to get assistance as a foreign country, which we need badly, and there is no paper work to worry about. If necessary, we will be glad to declare war and lose. However, if this is a requirement, we would appreciate being able to surrender real quick, as our Mayor works as a nurse in a hospital, and most of our council members work in a nearby mine and cannot get much time off from work.

In addition to Anderson and Randall, the signatories were city clerk Margaret Medure and councilmembers Lloyd Linnell and Myron Holcomb.

After a month without a reply, Anderson sought help from Veda Ponikvar of the Chisholm Free Press. (Like Anderson, Ponikvar was well known on the Iron Range and later became a real-life character in W. P. Kinsella’s novel, Shoeless Joe; in the movie based on the book, Field of Dreams, Ponikvar was portrayed by Anne Seymour.) But even Ponikvar’s assistance had little effect.

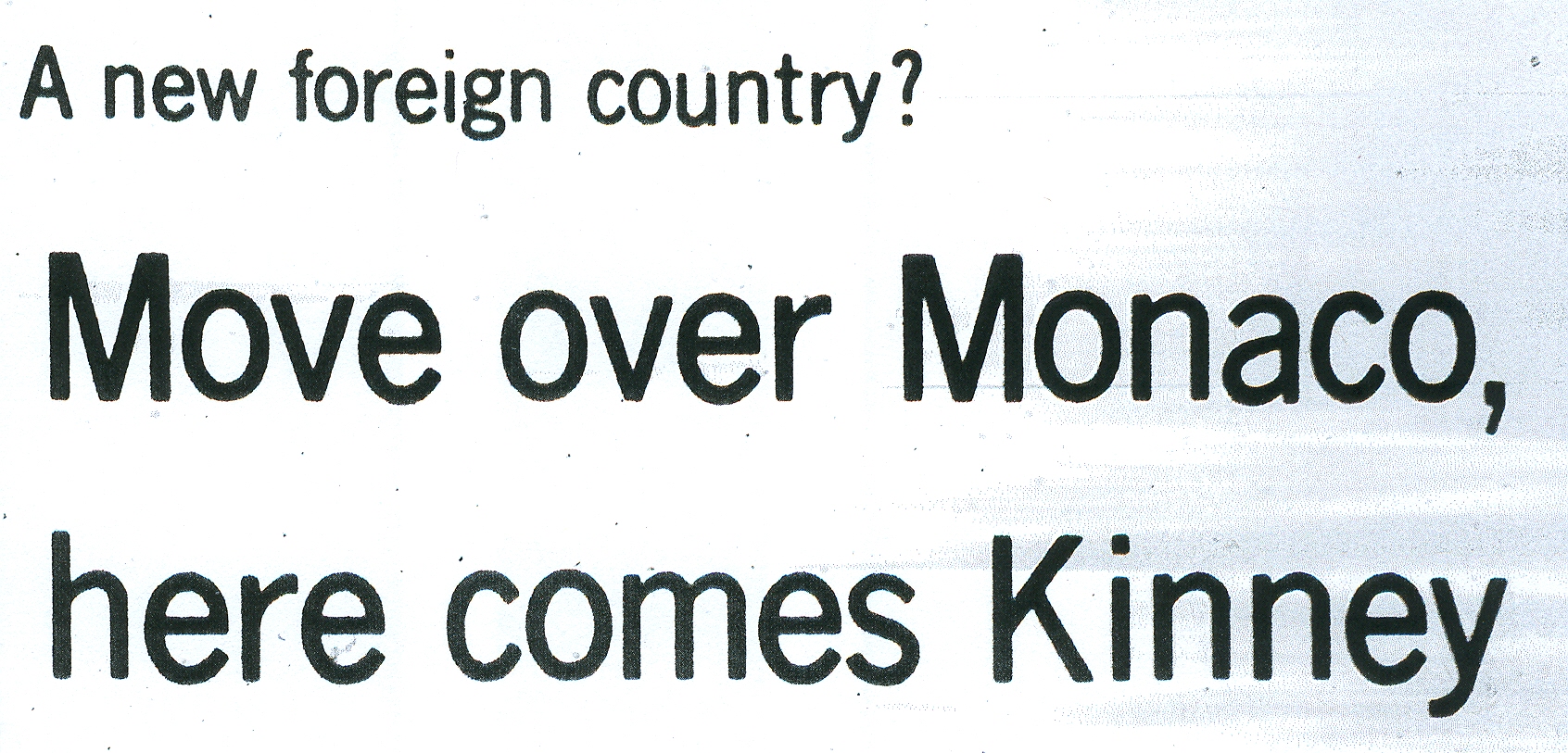

Finally, in early 1978, the widespread publicity came. It started with Ginny Wennen of the Mesabi Daily News of Virginia hearing the secession story. Young and enterprising, Wennen saw the potential for a story that would at least create smiles among readers. It did much more. “Move Over Monaco, Here Comes Kinney” was the headline over Wennen’s February 5 front-page story, which went wherever a 1977 version of “viral” might be. David Brinkley mentioned Kinney on the NBC Nightly News two days later, and the story spiraled through other news outlets.

About the same time, the city’s squad car broke down. Out of desperation, Anderson contacted Jeno Paulucci, a native of the Mesabi Range and a tycoon in ventures ranging from pizzas to periodicals. A man who admired spunk and operated with flair, Paulucci donated a used Ford LTD emblazoned with a “Republic of Kinney” logo to replace the squad car, and he threw in a box of 10 cases of his pizza mix—all to grand publicity, of course.

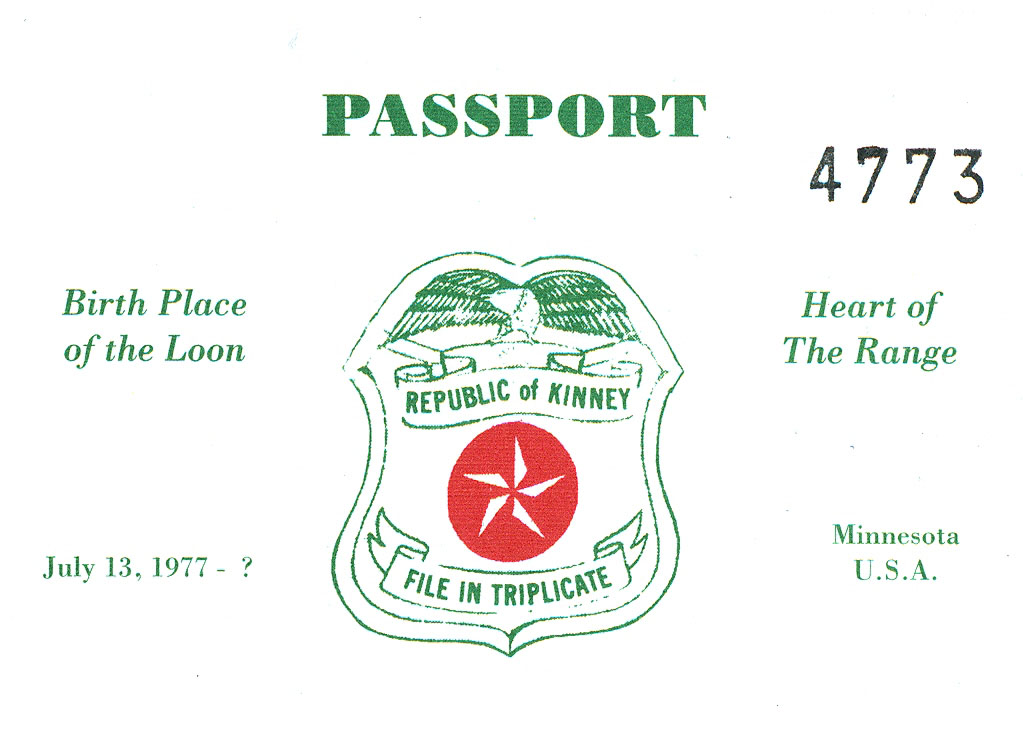

Seeing a turn in the tide, the new republic embraced its independence. Kinney created a passport for its residents with a logo that contained the slogan, “File in Triplicate,” homage to the red tape they had unsuccessfully meandered through before. Wennen continued to write stories, as did others. Not everyone embraced the movement. From within the Iron Range itself and throughout the country, some blasted Kinney for its lack of self-sufficiency. (One critic suggested a literal blast with an anonymous letter indicating hope that the U. S. government would use Kinney “as a test site for one of their neutron bombs.”)

The detractors, however, were in the minority, and the overall reaction was positive. In March 1978, Hibbing-native and Minnesota governor Rudy Perpich became the first non-resident to receive a passport, and Kinney began selling them to outsiders as a fundraising effort. Others pitched in, designing a flag and donating a canoe so Kinney could have a Navy.

After conventional efforts produced little, Kinney’s innovative approach worked. “The publicity we generated had the desired effect,” said Randall. By the end of March 1978, Kinney received a grant of $60,000 from the Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board (IRRRB), a state development agency designed to advance economic growth on the Iron Range. By the end of the year, the IRRRB added another $138,000, enough for Kinney to replace its water and sewer lines and drill a 450-foot-deep well.

The headline in the February 5, 1978 Mesabi Daily News

Even with a functioning water system, Anderson’s bar and her apartment atop it burned down in 1995. The locals chipped in and quickly a pair of structures went up on the site, one for Anderson to live in and the other for the bar, which remained the unofficial headquarters of the Republic of Kinney. In 2002 Anderson wrapped up her tenure as mayor and also sold the bar to Larry Hauta, who grew up in the area. The Kinney offices, just across the street, have limited hours, so the bar (now Liquid Larry’s) is still the place to obtain a passport. Hauta maintains a record of all who buy one and continues the long tradition of screening non-residents with a “visual inspection and a handshake.”

By the early 1980s the water system had been fixed, but ongoing challenges remained, ones inherent to the Iron Range with its cyclical history of shutdowns and layoffs. Kinney carried on and, with Anderson as grand marshal, celebrated its 30 years of independence with a Secession Days Festival and a Republic of Kinney Day in July 2007. Anderson died three months later. Numerous political leaders, including Mark Dayton (between stints as a U. S. Senator and Minnesota Governor), attended.

Kinney’s population was 152 when Anderson died. It’s now under 150, and its future as a town is uncertain. But its legacy as a Republic lives on.

Footnote:

Secession was nothing new to Kinney in terms of innovative solutions. George Rekela, who grew up in Kinney, told of the time the city needed a night patrolman and was able to cheaply contract with the town’s Peeping Tom because, as Rekela said, “They figured he was already out there anyway. . . ”

|

|

Liquid Larry Hauta keeps the secession spirit alive by selling Republic of Kinney passports and maintaining a display of its history. Liquid Larry’s still has the faded Grain Belt sign, which survived the 1995 fire and is a vestige of Mary’s Bar.

Needs Remain

While Kinney got the funding to fix its water system, infrastructure needs remain for public water suppliers across Minnesota and the country. Drinking water infrastructure includes everything from the water source to meters in people’s homes. It includes wells and well houses, pumps, treatment facilities, storage units, distribution pipes, power sources, and computer systems. Current infrastructure needs for Minnesota total nearly $1 billion, and the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the state will have to invest approximately $7.5 billion over the next 20 years to upgrade community public water systems to comply with the Safe Drinking Water Act. More than half of the current financial need is for water systems serving fewer than 3,300 people.

As a result of the changes in legislation to two key grant programs in Minnesota in 2017, the Water Infrastructure Fund (WIF) and Point Source Implementation Grant (PSIG), the grant funding for drinking water projects has increased over the last several years. Funding totaled $17.5 million in fiscal year 2019. WIF provides grant funding based on an affordability threshold, allowing needed and costly drinking water infrastructure projects to be completed. PSIG is a grant program designed to help communities address limits placed on wastewater discharges and assist public water systems. Both of these programs, when linked to the Drinking Water Revolving Fund, have put many needed drinking water infrastructure projects in reach for communities across Minnesota.

In recent years, Kinney has also received a pair of Source Water Protection grants totaling nearly $11,000 from the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH).

Though available grant dollars increased over the last few years, grant dollars still do not cover total project costs, so systems have to find other funding mechanisms for projects, such as Drinking Water Revolving Fund loans as well as the U. S. Housing and Urban Development Small Cities Development Program and the Department of Agriculture Rural Development. Organizations such as MDH and the Minnesota Rural Water Association are assisting water systems with financial and asset management planning and working to coordinate funding programs to optimize the use of available funds.

Current programs and funding tools make it more likely that cities will receive the support they need to remain viable and maintain the economic development that depends on a safe and reliable source of water without having to declare war on the United States.

Go to > top.