Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Lewis and Clark Regional Water System Nearly Complete in Minnesota

From the Winter 2018-2019 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

Off a dusty crossroads stands a marker designating the site where Minnesota, Iowa, and South Dakota meet. These three states have come together in another way, with the creation of the Lewis & Clark Regional Water System. A treatment plant near Vermillion, South Dakota, several miles north of the Missouri River, now processes more than 23 million gallons per day to distribute to the tri-state area. Its capacity may one day reach 60 million gallons per day.

The photos below show work progressing on a pipeline between Luverne and Worthington as well as a 4-million gallon reservoir in Rock County, just south of Luverne.

The tentacles of the Lewis & Clark Regional Water System (LCRWS) are nearly fully extended. Worthington will be the last stop in Minnesota, nearly 30 years after the city signed an agreement to be a partner in the project.

Lewis & Clark was conceived in 1988 with a simple idea: take water from a plentiful source and transport it to unplentiful places. The plentiful source is the Missouri River at Vermillion, South Dakota. The unplentiful sources range in different directions as far as 60 miles away.

Twenty members—in South Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota—put up money to reserve certain amounts of water. The Minnesota partners are Rock County Rural Water District, Lincoln-Pipestone Rural Water System, and the cities of Luverne and Worthington.

The system was originally envisioned at 23.5 million gallons per day (MGD). However, after authorization in 2000, members requested additional water; as a result, the system and plant were designed for 45 MGD with the ability to expand to 60 MGD in the future.

Source and Treatment

Eleven wells draw from an aquifer that is recharged by the adjacent Missouri River at Vermillion. For South Dakota and beyond, the Missouri River is “the greatest natural water resource available,” according to LCRWS operations manager Jim Auen. “It is high-quality, abundant, and drought resistant.”

Through 54-inch pipes the water is pumped to a massive treatment plant north of Vermillion, which has been built in two phases, totaling approximately $90 million. Phase 1 (high service pump station, underground reservoir and electrical switchgear building) was $23.2 million, and Phase 2 (the main treatment plant) was $66.6 million.

The three-level plant has more than a quarter-million square feet, with room for expansion. The water is softened to reduce total hardness from approximately 300 parts per million (ppm) to 160 ppm. The lime in the softening process raises the pH, so a carbon dioxide feed system and recarbonation basins are used to adjust the pH before filtration.

The eight sand-and-anthracite filters, which have a Leopold underdrain system, remove iron and manganese. Sodium hypochlorite is added with ammonia for disinfection. Fluoride is also added. The treated water has total dissolved solids reduced to fewer than 500 mg/L.

Next to the plant is a 4.5 million gallon underground reservoir with a high service pump station and electrical switchgear building in addition to a nearby decant pond and three lime drying beds.

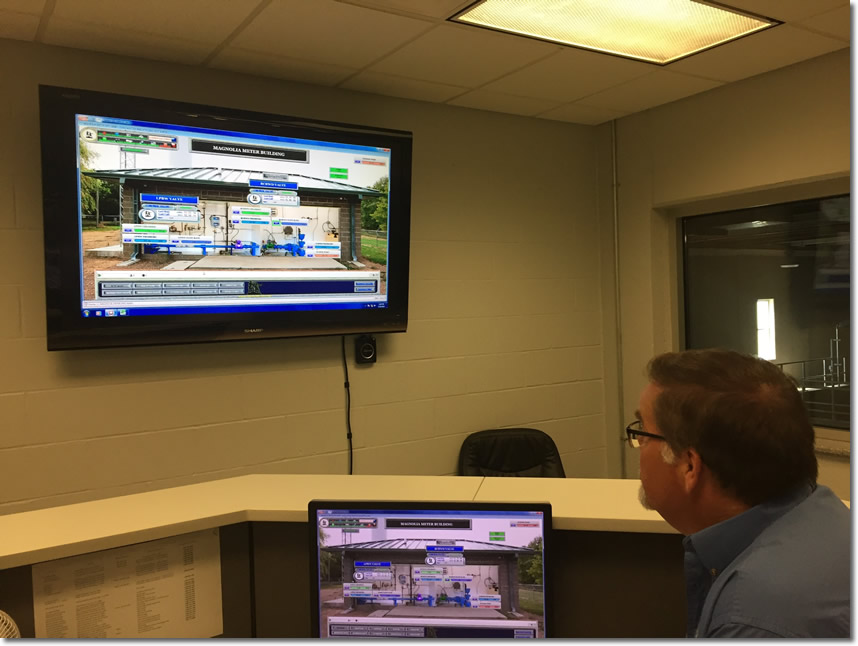

From the treatment plant in South Dakota, operations manager Jim Auen monitors the activity of a meter building in Magnolia, Minnesota.

Distribution

The water is sent 50 miles north to Tea, which is the hub of the entire system. Just south of Sioux Falls, Tea has a pair of 7.5 million reservoirs flanking a pump building. Some of the water from the plant has already branched off to communities in South Dakota and Iowa, although 90 percent of the water passes through Tea, including the water to Minnesota.

In July 2012 the system’s first water was pumped, to Sioux Falls and several smaller communities along the way, as well as to Rock Rapids, Iowa. The Minnesota members—being the farthest from the source—were the last to receive water. In May 2015 the project reached Minnesota, crossing the state line to deliver water to Rock County Rural Water District outside Luverne.

Since then it has gotten to Luverne and Lincoln-Pipestone Rural Water System, which serves an area that includes 38 cities in 10 counties. Along the way, connection points in Magnolia and Adrian have been hooked up. The water has allowed Luverne to be the site of Minnesota’s first shrimp hatchery and harbor, a commercial-scale shrimp producer. Construction on the $48 million facility, which will produce 150 million shrimp a year, will start in 2019.

LCRWS executive director Troy Larson and construction administrator Clint Koehn (above) at the system headquarters in Tea, South Dakota, just a few miles from the Tea reservoirs and pump station (below).

Worthington

Though Worthington was the first Minnesota partner to sign up, it will be the last in the state to connect. By highway, it is 115 miles from Vermillion, the most remote city on the system. Worthington is directly on border of the Mississippi/Missouri River watershed. Its wellfield is surrounded and fed through groundwater/surface water interaction by man-made Lake Bella, seven miles to the south. With an average depth of fewer than 100 feet, the wells are susceptible to contamination and sensitive to drought.

Conservation is a way of life in Worthington, which has an aggressive leak detection program and high reclamation of backwash water. The city has also been creative in partnering with other organizations, including Pheasants Forever chapters, in source water protection, purchasing and setting aside land for conservation. “We have partners willing to do things that were unheard of in the past,” said Worthington water superintendent Eric Roos. (Learn more by watching Invisible Heroes: Worthington).

The ongoing need for water caused Worthington to become the first partner outside of South Dakota to reserve water. As the network of pipes extends west from Luverne to Worthington, LCRWS has constructed a meter building next to the Worthington water treatment plant while the city is building an adjacent high-service pump station. The pump station will receive water out of both the city’s ground storage and from the Lewis & Clark supply to send out through its distribution system. “We’re going to put out a consistent blend to our customers,” said Roos.

To the left of the Worthington Water Treatment Plant are a meter building and reservoir, part of the Lewis & Clark Regional Water System.

Reaching the Finish Line

As the Minnesota portion of the project wraps up with Worthington as the 15th overall partner to connect, five more systems still await their water—four in Iowa and one in South Dakota.

The financing is covered on an 80-10-10 system: 80 percent from the federal government, 10 percent by the states, and 10 percent by the individual members. To this point, the states and local entities have paid 100 percent of their costs. Approximately $188 million is still coming from the federal government. Troy Larson, executive director of Lewis & Clark, says the Congressional delegations from the three states have been supportive, and he noted the efforts of Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton, particularly with advances for eventual federal funding.

The total project cost is estimated at $605 million, with over half the capital cost for the construction of the distribution system, which will have more than 332 miles of pipes.

When the project is completed, more than 300,000 residents—not to mention significant industries—will be receiving Lewis & Clark water over 5,000 square miles, a service area the size of Connecticut.

The softening basins (above) and filters (below) at the Vermillion plant. The pipes on the filters have been stubbed to allow for expansion with an addition to the building to the north.

Of Interest

Worthington Explores Lewis and Clark

Go to top