Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

New Brighton Cleans Up

From the Summer 2003 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

"I still remember Gary Englund coming to give the bad news to the city council," said Les Proper.

"I still remember Gary Englund coming to give the bad news to the city council," said Les Proper.

In July of 1981, Englund was head of the Minnesota Department of Health's Section of Water Supply and General Engineering (later the Drinking Water Protection Section) and has recently retired from that post. Proper was in his fourth year as public works director for the city of New Brighton, a position he still holds. The bad news was the discovery of trichloroethylene (TCE) and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the city's water supply.

The health department had been notified by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency of the presence of TCE in Round Lake in Arden Hills, just to the east of the city line with New Brighton. Englund said they looked at the direction of the groundwater flow, which was southwest toward the Mississippi River, and began sampling both municipal and private wells in New Brighton. Some of the wells had TCE levels of several hundred parts per billion (ppb), including a mobile home park that had a well with 440 ppb. Although TCE wasn't yet regulated (it now has a maximum contaminant level of 5 ppb), it was clear that there was a health risk that needed an immediate response.

"They took the bull by the horns," Englund said of New Brighton city officials. "They started taking care of the problem right away."

From stop-gap measures to a long-term solution, New Brighton responded to the crisis with a partnership and plan that allows for remediation of a highly contaminated aquifer while providing a safe supply of water for New Brighton as well as a supplemental supply for the neighboring suburb of Fridley.

History

New Brighton drilled its first two municipal wells in the 1940s, a time when the area was emerging from a small farming community to a bustling suburb of St. Paul. The post-World War II baby boom swelled the population and greatly increased water usage. By the 1970s, the city had eight wells, all in the Prairie du Chien/Jordan formation, to meet the demand, with treatment consisting of disinfection and fluoridation.

Discovery of contamination

The sampling done by the Minnesota Department of Health in 1981 discovered trichloroethylene, a degreasing solvent extensively used by industry, along with quantities of trichloroethane, dichloroethane, and dichloroethylene. All are suspected carcinogens.

New Brighton responded to the contamination in several ways. It began a weekly testing program to monitor contamination in the various city wells and then changed the sequencing of its pumping and well use to draw water first from the wells showing the least contamination. The city also implemented strict conservation measures, including lawn-sprinkling restrictions. Public information was a key part of the response, and Proper says the residents, while concerned, were cooperative.

Meanwhile, New Brighton looked at its options for dealing with the problem. Treatment for the removal of VOCs was an emerging technology in the 1980s and not seen as a viable choice at the time. Purchasing water from the city of Minneapolis was considered but rejected. Finally, the city decided to get away from the contaminated aquifer and go deeper into the ground.

New Brighton stopped using wells 2 through 7. Its remaining wells (8 and 9) were sealed off in the Prairie du Chien and Jordan aquifers and extended into the Mt. Simon-Hinckley formation in addition to drilling three more deep wells (numbers 10, 11, and 12).

Water from the deeper aquifer was free of the harmful contaminants but was high in iron, which causes aesthetic problems. "We got the first two wells in and had horrible iron problems," said Proper, adding that the residents "at least knew it was iron and not TCE and were thankful to have the aesthetic problem rather than the chronic problem."

Nevertheless, the city dealt with the aesthetic issues by installing iron-removal devices at four of the five wells (all but well number 9). "Iron is pretty easy to precipitate out," Proper explained. "With aeration and chlorine, the iron comes right out, and it goes through a sand filter, and they can backwash that out." The wells pumped into the gravity filter, and a booster pump then sent the water from the bottom of the filter into the distribution system.

While effective, the measures were costly. The addition of the wells and filters came to more than $3 million, an amount financed with grants as well as levies on the citizens, who passed a bond referendum.

Identification of source

By 1984, the groundwater contamination had become one of the largest Superfund sites in Minnesota. A 24-square-mile area, which includes portions of New Brighton, St. Anthony, Arden Hills, Shoreview, Mounds View, Columbia Heights, and Minneapolis, was placed on the national priorities list.

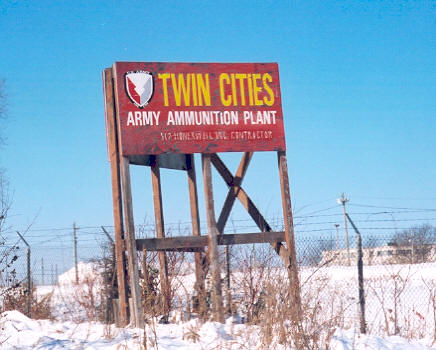

This area included the Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant (TCAAP), a 3.75-square-mile site in Arden Hills to the northeast of Round Lake, and it was becoming clear that this was the source of the TCE contamination. A government-owned, contractor-operated federal facility, TCAAP moved onto the site in 1941, and its primary purpose had been the production of ammunition in support of military operations.

TCAAP's tenants used production and waste-disposal practices, including the release of contaminants into the soil, that were widely accepted at the time. The result was a large plume of contaminated groundwater beneath Arden Hills, New Brighton, and St. Anthony. The plume, which exists primarily in the upper portion of the Prairie du Chien aquifer, is approximately six miles long and up to one mile wide. Its axis runs beneath Silver Lake Road, a north-south street in New Brighton. The plume is estimated to be flowing at the rate of 1,000 feet per year toward the Mississippi River.

New Brighton filed suit against the U. S. Army, and in 1987 a landmark agreement was reached. The Army agreed to reimburse all past city costs and to finance construction and operation of a city-owned water treatment facility with an innovative pump-and-treat approach that would serve the dual purpose of providing a safe water supply to New Brighton while also cleaning up the aquifer. In fact, the settlement agreement between the city and the Army requires New Brighton to use the treated water for at least 80 percent of its total usage to ensure enough pumping to prevent migration of contaminants to other parts of the aquifer and to hasten the remediation process.

The result of this agreement has been Minnesota's largest groundwater cleanup process.

|

|

|

The Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant in Arden Hills was identified |

Treatment

With the addition of treatment, the city was able to go back to the wells it had discontinued. Of those, only wells 3 and 4 drew from both the Prairie du Chien and Jordan, which are hydraulically connected. The other five drew water exclusively from the Jordan. Fearing that too much pumping from the Jordan could draw the contamination downward through the dolomite in the Prairie du Chien formation, the city relied more on the multi-aquifer wells while completely abandoning two of the Jordan wells (numbers 2 and 7).

After studying a variety of treatment alternatives, New Brighton opted for granular activated carbon (GAC) as the means of removing the VOCs from the water. A temporary GAC system was designed by Barr Engineering Company of Edina and used in 1988 and 1989 before the Permanent Granular Activated Carbon (PGAC) plant, with a capacity of 5 million gallons per day, opened in June of 1990.

The PGAC plant consists of 16 vessels, each 24 feet high and filled with 20,000 pounds of carbon, which provides a column 10 feet in diameter and approximately nine-and-a-half feet deep. The effectiveness of the granular activated carbon is based on the surface area provided by its enormous porosity. One of the informational signs in the plant points out that a handful of GAC has the surface area of a football field. As the water goes through the vessels, the organic impurities adhere to the surface of the carbon granules. Screened nozzles at the bottom retain the carbon within the vessel while allowing the water to pass through.

The vessels are grouped into eight pairs, and the incoming water is split evenly between the pairs. The water passes through each pair in series, first through the lead vessel and then through the lag vessel. In between the vessels is an instrument panel showing the influent pressure, effluent pressure, and flow rate.

The use of two vessels provides a high level of protection with the lag vessel ensuring the removal of the contaminants to non-detectable levels. The water is sampled on a regular basis, and when the monitoring indicates that the organic impurities are not being completely removed, the carbon in the lead vessels is replaced. The carbon is transferred into and out of the vessels through pressurized hoses on bulk-transport trucks. The used carbon is then recycled and used in wastewater treatment processes.

After carbon is replaced in the lead vessels, the order of treatment in the vessels is reversed. The vessel that has not had its carbon replaced becomes the first in line, and the one with the fresh carbon becomes the lag vessel. This ensures that there is always an unused supply of carbon to remove any traces of contaminants that might pass through the lead vessel.

Following the opening of the PGAC facility, changes continued with the treatment process in the early-to-mid 1990s.

|

|

Each of the vessels at the PGAC plant

contains 20,000 pounds of carbon. |

|

| Les Proper (left) with utilities superintendent Dave Olson |

The Army wanted more water pumped as a means of containing the aquifer. The remediation goal was 4.6 million gallons per day, much more than the city can use. To solve this issue, New Brighton entered into an agreement with Fridley to take the excess water. A 20-inch interconnecting pipeline now runs between the cities. "We use it all," said Dave Olson, New Brighton's public works superintendent. "That which we can't use, we send to Fridley." Fridley pays only for the chemical addition of the water sent from New Brighton.

The development of a second contamination plume brought about another change, the construction of a second treatment plant, the Plume Groundwater Recovery System (PGRS), and drilling of a well to serve that facility.

The original plume encompassed the city's existing well field. The new one, to the south and east, appeared to be emanating from the site of Alliant Techsystems (formerly Honeywell), one of the contractors at TCAAP. "Alliant Techsystems and the Army came to a facilities agreement where they divided up some responsibility for the contamination on the site," explained Proper. "We suggested to Alliant that they let us handle it with a second treatment plant, similar to what had been done with the north plume. We partnered with them and built that facility."

The PGRS is similar in operation to the PGAC plant although much smaller, containing just six carbon vessels, each 24 feet high and 14 feet in diameter. The PGAC plant was designed for 3,200 gallons per minute (gpm), the PGRS for 1,200 gpm.

The new well and PGRS facility was sited next to the city garage, about a mile east of the PGAC plant. However, Proper said the south plume "never really materialized the way they expected it would" and offers a theory as to why. Proper believes that the original plume shifted, creating the south plume, as a result of their shutting off the water supply from the Prairie du Chien and Jordan aquifers and switching to the Mt. Simon-Hinckley in the 1980s. After the deal was reached with the Army and the city went back to its wells in the Prairie du Chien/Jordan formation, the south plume began receding.

Around the same time the Fridley interconnection and PGRS was being completed, the city drilled two more wells. "The Army felt they could get more mass removal with better located wells," Proper said. "The addition of wells 14 and 15, which go to PGAC, went into a different part of the aquifer that was drawing more iron and manganese. So the Army paid for an addition to the PGAC plant and new greensand pressure filters to remove iron and manganese."

An addition to the PGAC plant was made to house the pressure filters, which consist of 12 inches of anthracite coal on top of 18 inches of manganese greensand with a 12-inch gravel base. Air, chlorine, and potassium permanganate are injected into the water to oxidize the iron and manganese prior to the water entering the filters. The anthracite coal filters out the large-sized iron and manganese particles. The manganese greensand not only removes the smaller iron and manganese particles, but, because of its unique chemical properties, also oxidizes any manganese remaining in solution.

The filters, each 10 feet in diameter and 43 feet long, are divided into five separate cells to provide the water velocities required to backwash the filter, which is done about once a week. Each cell has separate piping and valves for the water inlets and backwash water outlets.

The Plume Groundwater Recovery System plant, which opened in 1994.

On-Site Cleanup

While New Brighton does its part to clean up the aquifer and provide its residents with safe drinking water, the Army has proceeded with cleanup efforts of its own on the site.

The Army initiated soil cleanup to remove subsurface contaminants before they reach the groundwater and also installed a "Boundary Groundwater Recovery System," consisting of 17 extraction wells-12 around the perimeter of the installation and five inside it, close to the sources of contamination-to block further migration of contaminated groundwater. The wells extract 110-to-125 gallons of contaminated water each month for treatment at a large plant on-site where four air stripping towers remove the contaminants. The treated water is then sent to a gravel pit at the center of the installation to replenish the aquifer.

This system is projected to reduce trichloroethylene levels in the aquifer from an average of 2,000 parts per billion to 20 ppb in 50-70 years of operation.

Current Status

The Army no longer uses TCAAP to produce ammunition, but it proceeds with its remediation efforts in what has become Minnesota's largest Superfund site and what remains as one of the largest trichloroethylene plumes in the country.

The city of New Brighton continues playing an important role in this process as its residents enjoy a plentiful supply of safe drinking water as a result.

Learn more by watching Invisible Heroes: New Brighton

Other Invisible Heroes videos:

- Invisible Heroes: Worthington

- Invisible Heroes: Fairmont

- Invisible Heroes: St. Martin

- Invisible Heroes: Oakdale

- Invisible Heroes: St. Cloud

Of Interest

New Brighton Still Facing, Overcoming Water Challenges

Go to > top.