Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Sabin to Get Demonstration Plant for Arsenic Reduction

From the Fall 2004 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

Relief is on the way for Sabin.

Relief is on the way for Sabin.

This past July, the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approved a demonstration plant for arsenic removal for the northwestern Minnesota community (population 461), which is approximately six miles southeast of Moorhead.

The plant will enable Sabin to achieve compliance with the revised arsenic standard of 10 parts per billion (ppb), which takes effect in January of 2006, and it will help the city deal with a long-standing problem with iron in its water.

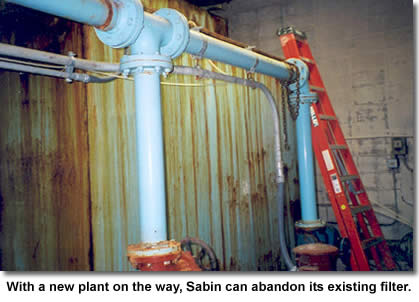

The existing plant, built in the 1950s, contains a pressure filter that is “pretty shot,” according to Gary Storms, who began dealing with the city's water issues when he became mayor in January of 2003.

The city has two wells, the second one being drilled in the 1980s as an emergency backup. Use of the wells is alternated, and both draw water with high levels of arsenic. Storms says that the water coming into the plant has arsenic at 44 parts per billion with only a modest reduction in finished-water levels. (The city's Consumer Confidence Report for 2003 shows an average level of 27 ppb in the treated water.)

“The filter is not filtering out anything—iron, manganese, arsenic,” Storms adds.

Sabin had planned to replace its filter as a result of the red water caused by the iron. The presence of arsenic actually delayed them in replacing the equipment. “The council, knowing that a new standard would be set for arsenic, waited for the EPA rule to find out what the new standard would be,” explained Storms. “They didn't want to move forward with a new plant only to find out that they wouldn't be able to meet the new arsenic standard.”

Once it was known that the maximum contaminant level (MCL) would be lowered from 50 ppb to 10 ppb, the city applied to become part of an Arsenic Treatment Demonstration Program administered by the EPA. The objective of the program is to evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of drinking water treatment technologies to meet the revised arsenic MCL under varying source water quality conditions.

The water systems selected for participation were matched with a treatment technology and vendor, and the system will operate the treatment facility for one year, then have the option to purchase the equipment and continue using it or return it to the vendor.

MDH engineer Karla Peterson noted that only about 30 water systems throughout the United States were chosen to participate, including three other Minnesota systems—Climax, Stewart, and Big Sauk Mobile Home Park. “Our systems were active in getting involved in the program, which is why Minnesota is so well represented,” Peterson said.

Through the EPA grant, the equipment will be provided to Sabin, which has to furnish a building to house the plant. The city will incur other costs associated with the project, including the piping to connect to the existing water and sewer distribution systems.

Storms estimates the total project cost will be $1.2 million, with $350,000 covered by the grant. In addition to the new plant, the city is purchasing meters at a cost of $70,000. Storms and council member Bob Dablow say their residents can expect a sizable jump in their water bills, from approximately $20 to $55 a month. The metering will promote conservation, which could decrease an individual user's bill. In addition, a proposed housing development could significantly increase the number of service connections—from 170 to 225—which will ease the burden on residents.

Storms estimates the total project cost will be $1.2 million, with $350,000 covered by the grant. In addition to the new plant, the city is purchasing meters at a cost of $70,000. Storms and council member Bob Dablow say their residents can expect a sizable jump in their water bills, from approximately $20 to $55 a month. The metering will promote conservation, which could decrease an individual user's bill. In addition, a proposed housing development could significantly increase the number of service connections—from 170 to 225—which will ease the burden on residents.

The city has held an open meeting on the water situation and addressed the issue at several other meetings that have been open to the public. Dablow says the public is “pretty understanding” and willing to pay the rate increases to get better water. He added that most of the concerns expressed by residents have been over the aesthetic qualities of the water rather than the arsenic.

Sabin has been working with Ulteig Engineers, Inc., of Fargo, North Dakota, in exploring options for dealing with its water-quality issues. In addition to new treatment, the city had considered purchasing water from the city of Moorhead, which is approximately nine miles to the northwest. The costs for the installation of a pipeline were comparable with the capital costs of a new plant. Storms and Dablow say their concerns went beyond the rates they might have to pay for purchased water. “By doing it ourselves,” says Dablow, “we control our own destiny.”

Storms echoes Dablow's adding, “We didn't want to be at someone else's mercy. Now we're at our own mercy.”

Storms says he hopes the new plant will be on-line by the spring of 2005.

Protecting Sabin’s Source: The Buffalo Aquifer

Sabin draws its water from the Buffalo Aquifer, a linear formation that extends to the north and the south. The city of Moorhead, which uses groundwater to supplement its supply from the Red River, has its wells in a coarse gravel trough in the lower part of the aquifer, to the east of Moorhead. Moorhead Public Service Water Division

Manager Cliff McLain says, “Sabin is off in the side [of the aquifer] in the sand, on what is considered to be a recharge area.”

Protecting the aquifer from contamination has been a top priority and one that McLain has been involved in for several years. He worked with the Minnesota Department of

Transportation (Mn/DOT) to protect the sensitive areas of the aquifer in the construction zone during the reconstruction of Minn. Hwy. 336 between Interstate 94 and U. S. Hwy. 10. The Mn/DOT controlled fueling and storage of equipment during the project to protect the aquifer and has lined storm-water ponds with a foot of clay at some of the ramps to the east of Moorhead. Unconfined and environmentally sensitive in this area, the Buffalo Aquifer has been contaminated with petroleum products as the result of truck stops at these highway interchanges. One of the truck-stop sites, on the south side of I-94 at Minn. Hwy. 336, was forfeited to the state for nonpayment of taxes in 1996. More than $1 million from the Minnesota Petroleum Tank Release Cleanup Fund, administered by the Minnesota Department of Commerce, was used to remove contaminated soil. Wastewater seepage lagoons also caused contamination at the site.

A fuel spill at a truck stop on the north side of the interstate prompted an investigation of the site, and gasoline released from the truck stop was discovered along with an old diesel spill. Petroleum-contaminated soil was removed from the site, and the truck stop has since been closed. Contamination from Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether (MTBE), a gasoline additive, is also present at the site.

Clay County has adopted a new zoning regulation to prohibit the storage and distribution of large quantities of petroleum products and hazardous materials from being located in the sensitive areas of the aquifer.

Of Interest

Arsenic in Minnesota’s Well Water

Minnesota Systems Treat for Arsenic

Arsenic Removal Comes to Climax

Go to > top