Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

St. Louis Park Water Supply Remains Reliable Despite Challenges

From the Summer 2014Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

|

| A May 1964 fire in the yards of Republic Creosoting produced more smoke than flames, but it lured many curious residents to the site. It was reported that the black smoke could be seen as far away as St. Paul, more than 10 miles to the east. |

Incorporated as a village in 1886 and taking the status of a city 68 years later, St. Louis Park is a suburb to the west of Minneapolis. It has been home to sports announcer and writer Halsey Hall, filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen, senator and comedian Al Franken, football coach Marc Trestman, and New York Times columnist and author Thomas Friedman.

Well drillers and plumbers who also made St. Louis Park their home and center of business operations played a major role in the development of a public water system that now serves 49,000 residents. McAlpine Well Company was formed in 1922 and located at 1333 Kentucky Avenue, near Wayzata Boulevard (now Interstate 394). Plumber Gust Hoglund began operations from his home in St. Louis Park in 1924, and within 10 years the village passed its first plumbing ordinance and had its first connection, by the Church of Holy Name, to the municipal water main. The Motzko family, now in its third generation of operation in St. Louis Park, was responsible for many of the early connections to the water supply.

Well drillers and plumbers who also made St. Louis Park their home and center of business operations played a major role in the development of a public water system that now serves 49,000 residents. McAlpine Well Company was formed in 1922 and located at 1333 Kentucky Avenue, near Wayzata Boulevard (now Interstate 394). Plumber Gust Hoglund began operations from his home in St. Louis Park in 1924, and within 10 years the village passed its first plumbing ordinance and had its first connection, by the Church of Holy Name, to the municipal water main. The Motzko family, now in its third generation of operation in St. Louis Park, was responsible for many of the early connections to the water supply.

E. H. Renner & Sons, currently located in Elk River, Minnesota, was started in St. Louis Park. The well-drilling company’s current president and chief executive officer, Roger Renner, was born into the firm in 1949, along with his twin brother, Ray, who is now the firm’s vice president. The family home and company headquarters then co-existed at 5800 Goodrich Avenue as the company was heading into its third generation of family leadership at the time and was already prominent in providing water to the rapidly growing area.

Today, St. Louis Park supplies water to residents from nine active wells, ranging in depth from 286 to 1,095 feet and drawing from the Prairie du Chien-Jordan, Mt. Simon-Hinckley, Jordan-St. Lawrence, Platteville, and St. Peter aquifers. The city used sand filters to reduce iron and manganese levels, but over time it became apparent that more effort was needed to keep the water safe.

Republic Creosoting

Beginning in 1917, the plant and yard of Republic Creosoting Company, a division of Reilly Tar and Chemical Corporation, covered 80 acres to the southwest of 32nd Street and Louisiana Avenue. Republic Creosoting distilled coal tar and made a variety of products, including creosote that was used to treat rail ties and other lumber at the site. The area was sparsely populated initially, but as the community grew following World War II, the appearance and odors of the site became a cause of increasing concern to residents as well as city and state officials.

The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) issued a report on the site as far back as 1938, noting pollution at the site from the creosote operations. By this time, problems were evident as St. Louis Park had already closed its first municipal well because of odor problems and a coal-tar taste.

In 1970 the newly created Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) sued Reilly Tar and Chemical; two years later, St. Louis Park purchased the land and took over responsibility for the cleanup. The site was deeded to the city’s housing and redevelopment authority and portions of the site later sold to private parties, who constructed a tavern, condominiums, and townhouses.

As the property became one of the first Superfund sites in the country in the early 1980s, the MPCA amended its original lawsuit against Reilly Tar and Chemical; in addition, city, state, and federal agencies pursued legal and administrative actions.

Reilly hired a consulting firm in Pittsburgh to help it deal with the lawsuits, and a young geologist named Bill Gregg got his first exposure to the issue. More than 30 years later, Gregg is still working on it. “This is my career project,” he said. The parties to the lawsuit reached a consent decree/remedial action plan in 1986, prompting Gregg to move to the Twin Cities, and he has continued to work with the company and St. Louis Park even while changing employers. For the past three years, Gregg has worked for Summit Envirosolutions, Inc. of St. Paul.

For decades the woodtreating process left lumber dripping with creosote that percolated into the water table. On-site waste disposal was through ditches that flowed to an adjacent wetland. Beyond that was the discovery on the site of an abandoned production well from 1917 that Gregg characterizes as “a poster child for the well code.” A down-hole camera in the well detected openings in the casing that allowed for contaminants to enter the Prairie du Chien aquifer. “If not for this well,” Gregg said, “a lot of the problems wouldn’t exist.”

Initial sampling was performed by MDH on St. Louis Park water in 1978, and several wells exceeded the guideline limit established by the World Health Organization. As a result, the city shut down six wells over the next three years, causing supply issues and resulting in water restrictions in St. Louis Park.

In 1979 MDH found a significant increase in breast cancer in women in St. Louis Park but concluded in a report to the Minnesota legislature six years later that it was unlikely that it was related to water contamination. “Neither the 1978 testing by MDH nor the subsequent testing that continues to this day has detected cancer-causing chemicals in the city’s water supply wells above safe levels,” Gregg emphasized.

However, one recommendation of the report was the creation of a statewide cancer surveillance system “to enable the systematic collection and analysis of cancer incidence data.” The Minnesota Cancer Surveillance System was established on January 1, 1988, and all cancers in Minnesota residents are reported to the Minnesota Department of Health.

|

| MDH engineer Bassam Banat sampled the water at one of St. Louis Park’s wells in the 1990s. |

Treatment

Dealing with supply issues and eventually treating the water to remove creosote chemicals was a major task for longtime water superintendent Scott Anderson, who recently retired; it is an ongoing one for Anderson’s successor, Jay Hall, and others in the utility, such as supervisors Bruce Berthiaume and John Laumann.

The city has added two water treatment plants with granular activated carbon (GAC). One, constructed in 1985, is located in the well field by Bronx Park, off Minnetonka Boulevard and Jersey Avenue. Hall said that water from two of the wells on the site passes through the sand and carbon filters. The other GAC plant, built in 1991, is in the southern part of the city, at 41st Street and Natchez Avenue, near the border with Edina.

|

| St. Louis Park added granular activated carbon treatment to its plant in Bronx Park and to another plant in the southern part of the city. |

Carrying On

With the consent decree nearing its 30-year anniversary, some objectives have been achieved, but the creosote remains buried at the site. “St. Louis Park groundwater will probably continue to require testing long into the future,” says Gregg.

The St. Louis Park Historical Society, which in 2001 produced a book on the city’s history titled Something in the Water, wrote:

Having a creosote plant in our town has been a mixed blessing. Of course there was the smell in the air, the taste in the water, and the fear of a health risk. On the other hand, the plant provided much-needed employment for many people over a period of some 65 years and produced valuable building products instrumental to the early growth of St. Louis Park and area railroads. It’s gone now, cleaned up and decontaminated—in fact, St. Louis Park has some of the most tested water in the state. But there are still some who wonder if there is “something in the water.”

|

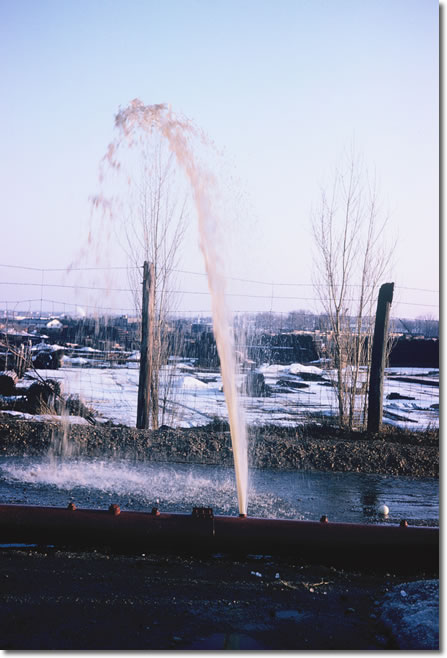

| A retention pond at 32nd Street and Oregon Avenue frequently overflowed and flooded adjacent homes. In the spring of 1965, the water also overwhelmed a lift station and drew a pair of nearby residents. (The smaller of the two lads in the above photo is now the editor of the Waterline.) The city pumped the water to higher ground through a 12-inch pipe and found that the system wasn’t child-proof. A local miscreant (not one of the two shown in the photo) unscrewed one of the caps on the pipe, resulting in a geyser, shown in the picture below with Republic Creosoting in the background. |

|