Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Community Commitment Results in Innovative Water Plant in St. Martin

From the Spring 2018 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

One of the newest water treatment facilities in Minnesota is also one of the first engineered biological water treatment plants in the state. Some other cities, such as Hutchinson, have partial biological treatment; however, St. Martin, a community of 343 people in central Minnesota, stands out with an entirely engineered biological plant.

Beyond the innovation in the plant is the strong community involvement in the project. Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) engineer Kim Larsen credits city clerk Cara Olmscheid, St. Martin’s only full-time employee, for her commitment to the project. Olmscheid, who notes that “city clerks have to wear many hats,” is knowledgeable about and involved in the water system in addition to the other duties she carries out each day.

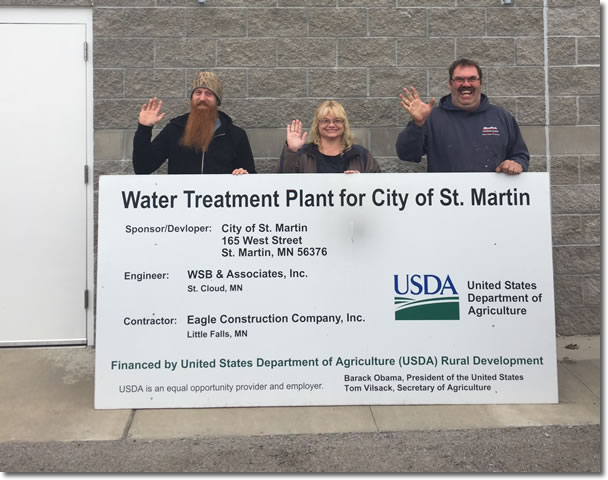

Olmscheid recognizes the support of James “Boots” Rothstein, a colorful native of St. Martin who has been mayor since 2002. Rothstein spent 35 years in New York, working for Chase Manhattan Bank, operating a restaurant, and serving 12 years as a detective for the New York Police Department, working undercover to infiltrate prostitution and pedophilia rings. Rothstein returned to his hometown to assist his aging parents and has also been active in combating human trafficking in the area.

Rothstein was president of the Sauk River Watershed District and, as mayor, the primary proponent in initiating the water project, according to Olmscheid. “As others sat back and talked about the cost, the mayor said, ‘We have to have good water.’”

|

|

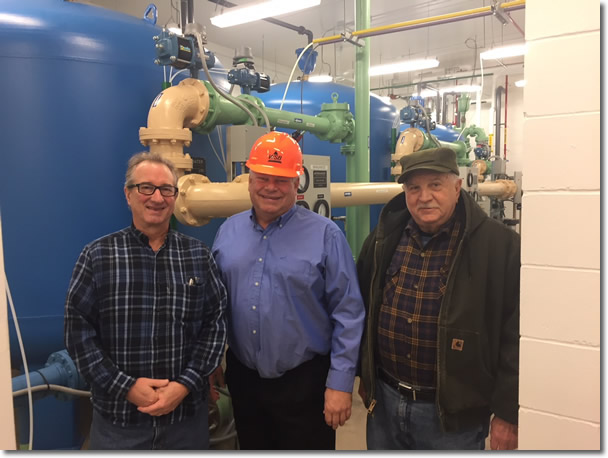

Above: Dave Schaaf of the Minnesota Department of Health, Dave Schultz of WSB & Associates, and Boots Rothstein, mayor of St. Martin. Below: The biological iron filter, the first of the chain of three filters. |

|

Sources

The city had been operating with two shallow wells (1 and 2), which had benzene levels above the maximum contaminant level (MCL). The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) installed filters at the wells that dropped the benzene to below detectable levels.

Olmscheid said in 2006 they discovered a hole in the casing of Well 1, prompting its sealing and the drilling of a new well (Well 3) next to it. The wells were near a creek and considered vulnerable to contamination. In 2011, the city found a hole in the casing of Well 2, and took it out of service, leaving St. Martin with only one well.

Meanwhile, Rich Soule of the MDH Source Water Protection Unit came to St. Martin and expressed concern about the location of Wells 2 and 3, especially since the creek that was the outfall of the wastewater treatment plant, which had a history of petroleum release. Because of the MPCA filters, Soule said, “There was no screaming need to get something done, but there was a concern, especially with two wells in the same aquifer,” adding, “Don’t put your eggs in one basket.”

The geology of the area is underlain with a granite shelf, making it difficult to find sites with a sufficient yield within the city limits, so St. Martin drilled two new wells to the east of the city.

Larsen said the current wells are considered nonvulnerable, in contrast to the shallow wells by the creek. However, high levels of iron and manganese in the ground caused aesthetic concerns, especially with the staining of fixtures in people’s homes. “It was awful,” said Olmscheid. In addition, high levels of ammonia are present in the new wells, although not as high as they had been in the previous ones.

During this period, St. Martin was meeting with the U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural Development regarding its wastewater and found out that rates that they qualified for, based on per-capita income, could be carried over to a water system.

St. Martin explored its options, worked with MDH, USDA, Tonka Water of Plymouth, Minnesota, and WSB & Associates, Inc. of St. Cloud, and settled on biological treatment, using naturally occurring bacteria instead of chemicals to remove contaminants. The city leased a trailer to do a pilot study, which was set up by Tonka Water and WSB & Associates, and city staff did the daily testing and pilot work. Olmscheid said they performed the studies for four months, wanting to make sure the innovative technology would work.

"It's more important to make sure it's done right

than it is to meet the deadline."

—Mayor Boots Rothstein

Treatment Process

The plant has three vessels. The first is a biological iron filter, which receives the water after air has been added to facilitate the biological oxidation of iron.

More air is then injected to facilitate the biological conversion of ammonia to nitrite and then to nitrate. “We’re not feeding any organisms,” said Dave Schultz of WSB & Associates, “just creating a robust environment for the natural bugs to grow biologically and convert the ammonia, letting nature do the work.”

The second vessel is an ammonia nitrification filter, in which two reactions occur. The first, the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite, is by the nitrosomonas genus bacteria. The next is by the nitrobacter genus to convert the nitrite to nitrate.

Oxidized manganese and any remaining biological matter are filtered with anthracite and greensand in the third vessel.

After filtration, three chemicals are added: fluoride for dental care, chlorine for disinfection and to maintain a residual in the distribution system, and a corrosion-control inhibitor.The filters are backwashed with non-chlorinated water from a concrete backwash holding tank in order to not disrupt the bio-growth on the filter media.

Construction began in July 2016, and the total project cost just more than $3 million, which included the plant and related infrastructure. Approximately 45 percent of the amount came from a grant and the rest from a 40-year loan at an interest rate of 1.875 percent, both from USDA Rural Development.

Asset Management

St. Martin has been forward-looking in other ways, according to Larsen, who pointed out that most small cities with only one full-time clerk and a few operators do not have the time and resources to develop an asset management plan. “St. Martin has spent many years focused on the future of the water system.” Utilities, typically larger ones, use asset management to maintain their infrastructure in a controlled and planned manner, to set water rates in a way to offset the need for loans, and to keep operating without disruption.

A detailed list of assets—wells, valves, meters, storage facilities, pipes, and service lines—helps cities develop a plan on how to maintain and/or replace them and to head off emergency situations that may disrupt service and cause unexpected expenses. “St. Martin has good information because the city clerk [Olmscheid] has an excellent understanding of the importance of infrastructure. She enjoys solving problems, getting funding, and seeking to better the town. And [she’s] not afraid to spend money. The person or persons in charge of the checkbook are critical drivers in having a CIP [capital improvement plan] or asset plan.”

The new treatment plant went on-line in September 2017. Larsen credits Olmscheid and other city leaders for their commitment to the water system.

“We were keying on this because of the community involvement,” said Larsen. “Everyone was so excited about it. That’s terrific.”

The Minnesota Department of Health worked with the city on a video of the new treatment plant:

Other Invisible Heroes videos:

- Invisible Heroes: Fairmont

- Invisible Heroes: New Brighton

- Invisible Heroes: Worthington

- Invisible Heroes: Oakdale

- Invisible Heroes: St. Cloud

Of Interest

Biological Filtration Used in New Hutchinson Water Plant

Go to top