Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

A Look at Water Towers

Water Towers Serve as

Identifiers, Reminders, Landmarks

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

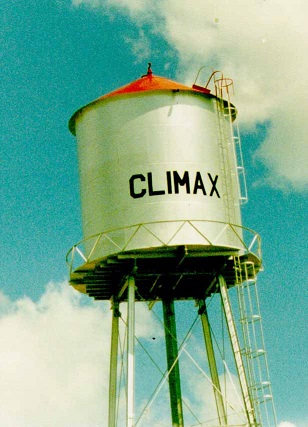

For many communities, a water tower is a part of its identity. Driving through the prairies of Minnesota, travelers are alerted to the coming of a town by the sight of a water tower poking up beyond the horizon.

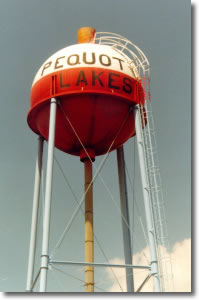

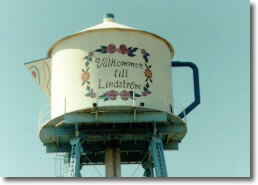

Some cities are bolder with the identification they put on their water towers. The Barnum water tower proudly proclaims itself “Home of the Bombers,” and Buhl uses its tower to lay claim to “Finest Water in America.” The tower in Staples notes “100 Years of Progress” while the back side of the water tower in Sauk Centre serves as a reminder to its “Original Main Street.” Pequot Lakes needs no further words to inform visitors of its great fishing. Its water tower—with red on the bottom and white on the top—is in the shape of a bobber. An even different shape is the tea-kettle look of the tower in Lindström.

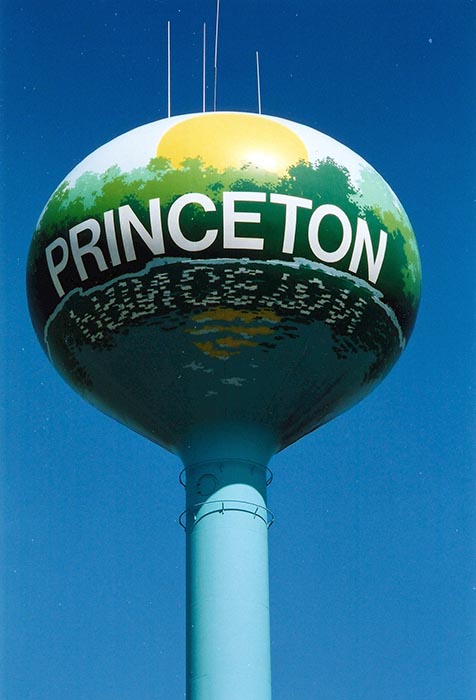

Even on conventionally shaped tanks, designs can be distinctive. Watertown lives up to its name with the bottom portion of the tower painted in the shape of waves. The cities of Sauk Rapids and Fosston took the effort to have their tower painted like a hot-air balloon. The city of Princeton also made the effort to make its tower a thing of beauty, with the letters of the town’s name reflected in a painting of a lake below the lettering.

Some towers, no longer storage vessels for water, still provide a historic function. The tower on the corner of Sixth and Washington—in the heart of Brainerd—was the first all-concrete elevated tank used by a municipality in the United States. It was widely pictured on postcards and maps and, even though it was drained in 1960 following construction of a new tower, is still the prominent feature in the city’s logo.

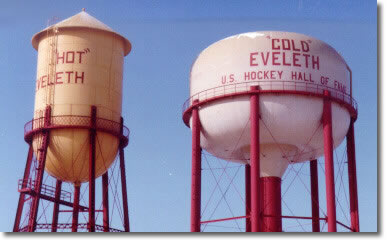

And, finally, some towers are now nothing more than fond memories. When Eveleth constructed a new tower next to the one it was replacing, the city identified the old one as Hot and the new one as Cold, prompting some visitors as well as residents to inquire if the city really had segregated its hot and cold water. The conundrums have come to a close, however, as the abandoned Hot tower was finally dismantled in the winter of 1996-97.

Where Are We?

It’s not just automobile travelers who count on water towers for their sense of direction. In 1960, a DC-3 carrying the Minneapolis Lakers basketball team drifted off course while bringing the team home from St. Louis. With electrical power gone and guidance instruments also disabled, pilot Vern Ullman buzzed a water tower in Carroll, Iowa in an attempt to find out where he was; alas, much of the town’s name was obliterated by snow, and all Ullman could make out were the letters “-L-L.” Fortunately, Ullman—still not knowing where was—was able to land the plane safely in an uncut cornfield.

More Minnesota water towers:

Go to > top.