Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Wild Rink Starts with St. Paul Water

From the Spring 2020 Waterline

Quarterly Newsletter of the Minnesota Department of Health Public Water Supply Unit, Waterline

A complete list of feature stories can be found on the Waterline webpage.

|

|

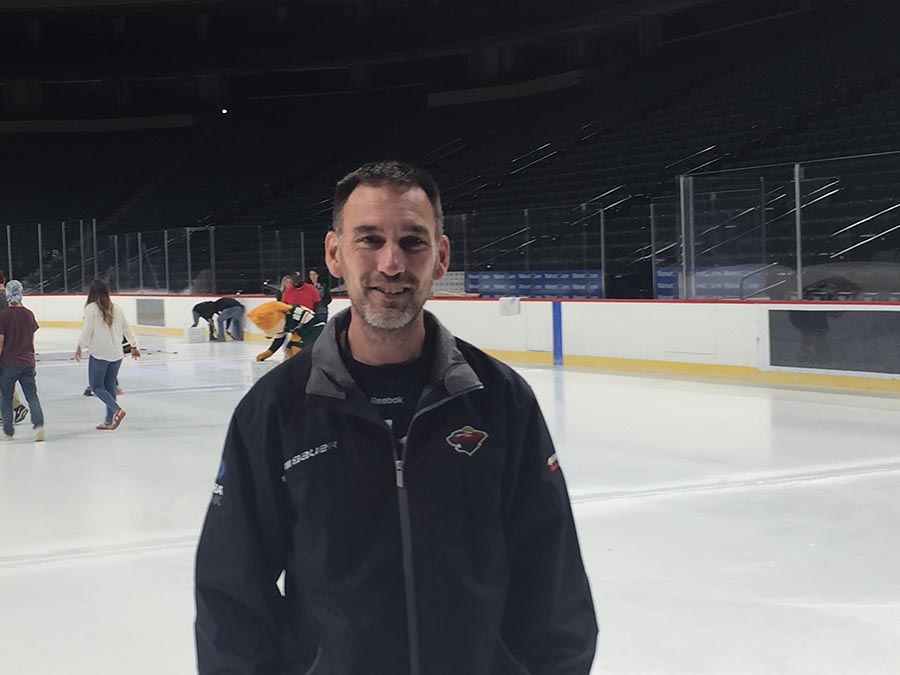

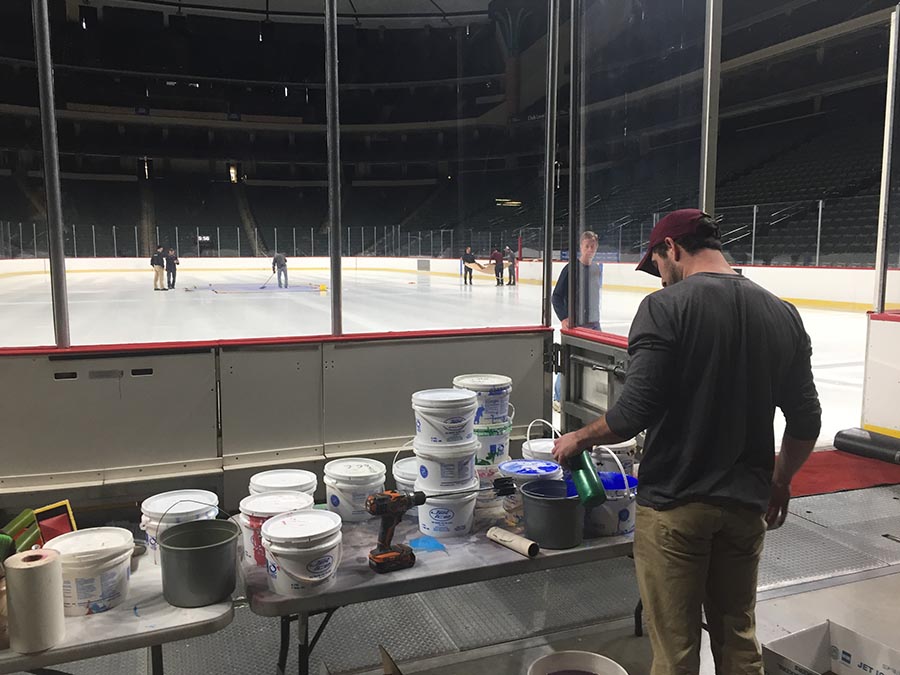

With a furry mascot overseeing the operation, lines and logos were painted on the rink of the Xcel Energy Center in preparation for the 2019-2020 Minnesota Wild System. Chris Aase spent the next morning applying water from St. Paul Regional Water Services to form the 1-1/4 inch thickness.

For Travis Larson and Chris Aase, the 2019-2020 Minnesota Wild season started in late August. That’s when they and their crews began the multi-day process of creating the ice sheet that soon would have the elite skaters of the National Hockey League (NHL) moving up and down it in front of sellout crowds.

The main ingredient in the process is tap water from St. Paul Regional Water Services. “It’s really good for making ice,” said Larson, the Wild’s senior manager of ice operations and events.

Larson, a self-proclaimed “mechanical geek,” worked at Minnesota North Stars games in the 1990s and then at various ice rinks in the southern Twin Cities suburbs after the North Stars moved to Dallas. He met Chris Aase in an arena and recreation facility management program at Minnesota State College Southeast in Red Wing. Aase went on to work at Target Center in Minneapolis, where he handled the house lights and maintenance.

Because of his training and expertise with refrigeration, Aase was the go-to guy for ice events, such as neutral-site NHL games held there during the period Minnesota was without major-league hockey. Larson came over to help out for those events.

Both men joined the Wild and the Xcel Energy Center when the NHL returned to the state in 2000. They oversee a crew of approximately 25 people, including 6 or 7 who go back to the inaugural season with them. (One, Mark Hegge, has been around since 1974 when he started working with the North Stars at the Metropolitan Sports Center – later the Met Center.)

|

|

Larson on the ice and Aase by the insulated panels.

The Main Ingredient

When the Xcel Energy Center first opened, Larson said they purified the water, using a de-ionizing system from Jet Ice, a company that provides products and services for ice arenas. However, the water was “way too pure,” according to Aase, who said they had some chipping problems with the ice, adding that after a half a season, they quit purifying the water. “It was ‘Voila!’ We went back to basic tap water and got better results.”

Larson said that St. Paul water, straight out of the tap, has about 150 parts per million of total dissolved solids, “about the same as Dasani.” A pair of 5-micron cartridge filters remove any other particulate matter. “That’s all that is needed,” said Larson. “It makes better ice, and the tap water binds the ice better than the purified water.”

The cartridges are capable of filtering 20 gallons per minute, more than enough to fill the 190-gallon tanks on the two Zambonis that shave the ice and put down a new layer between periods. (Each Zamboni uses only about half its capacity for each resurfacing.)

The filters above the Zamboni.

The Process

On Wednesday, August 28, the preparations began with reducing the temperature of the concrete base to about 16 degrees Fahrenheit with a network of cooling pipes beneath the floor. A skim coat of water binds the ice sheet to the concrete. Next, a whitewash consisting of biodegradable powder mixed with water was applied. After another skim coat, that evening the familiar design of the red line, blue lines, faceoff circles, and primary logos went on.

Season-ticket holders supplemented the regular Wild crew in applying the paint (a special type of paint provided by Jet Ice). In Tom Sawyer-like fashion, some lucky fans had been picked to do some of the painting, under the supervision of Larson, Aase, and others, including Nordy, the team mascot. A yarn line was placed to help the fans keep crisp red and blue lines. As important as those lines are, Larson said the critical line is the two-inch delineation between the goal posts. Often, video replay is needed to determine if the puck crossed the goal line. “That has to be perfect,” said Larson. “There is no room for anything to be off.”

|

|

The next morning, the rest of the ice was applied in a thin mist from a cart containing a 250-gallon plastic tank, a gas-engine pump, and spray booms. Aase drove the cart back and forth across the rink, taking the same path used by the Zambonis during games. Each full pass creates a layer 1/16 of an inch thick, and he can make two passes with one tankful. “It’s two passes, refill the tank, and repeat,” he said. The skating level of the ice is 1¼ inches thick and contains approximately 10,000 gallons of water.

The Changeovers

The Xcel Energy Center hosts other ice events, including hockey tournaments for the Minnesota State High School League and college conferences. The lines and circles remain, but the usual logos have to be covered.

The ice over the logos is dry shaved to 5/8 of an inch, and whitewash is applied to cover them. New logos go on top, and these areas are refilled. “The dry shaving creates a ‘natural bathtub,’” explained Larson. Water seeks its own level and refills the area of the dry shave. We just build that natural bathtub and flood it in.”

For dry events – such as concerts, basketball games, professional wrestling, and rodeos – the ice is covered with inch-thick insulated panels, each 4 x 8 feet. The panels can be installed, and removed, in a matter of hours. Aase said each Zamboni has a 77-inch long blade that removes ice, and a new layer does not have to be put on. Aase said he will do this the day after a concert to remove any beer that has seeped through the cracks of the panels.

Xcel Energy Center has hosted figure skating championships, and Aase said they used a thicker ice base for them. “Figure skaters use the depth of the ice for landing and takeoffs,” he explained, adding that events such as Disney on Ice have the same thickness that is used for hockey.

The finished product.

The finished product.

In addition to having selected fans participate in the pre-season painting the last few years, the Wild also introduced “This Is Our Ice,” in 2017, allowing fans to bring water from their hometowns—from taps, wells, ponds, lakes, and streams. The contributed water is filtered, disinfected, and mixed with St. Paul water before going onto the ice.

Unlike in baseball stadiums, where grounds crews have been known to doctor the field to the benefit of the home team, nothing like this is done in hockey. Aase said, “It’s all about fair play and safety.”

Larson echoed what Aase said, emphasizing the safety part “for every person who skates out here.”

Go to > top.