Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Waterline: Fall 2024

Editor:

Stew Thornley

Staff:

Noel Hansen, Erin Culver, Bob Smude, David "Hollywood" Rindal

Get email updates to The Waterline newsletter by signing up below. An e-mail notice is sent out each quarter when a new edition is posted to the web site.

On this page:

- Gary Englund remembers: Longtime section manager tells it like it was

- Applications open for Water and Wastewater Operator Certification Advisory Council

- Hennepin History Museum celebrates 1983 Circle of Water Circus tour

- New factsheet on lead in schools

- DWP doings

- More honors for Moorhead

- More from CISA on security

- Golden Spike for Lewis & Clark

- Another Drinking Water Institute in the books

- Quote of the quarter

- Reminder to all water operators

- Calendar

Gary Englund remembers: Longtime section manager tells it like it was

Gary Englund (left) accepts an award in 2000 from John Baerg, director for National Rural Water Association (center), in recognition of Minnesota’s ranking as the top state in the nation in drinking-water compliance. At the right is MDH deputy commissioner Julie Brunner accepting the award for Minnesota having the top health rates in the country.

During the year-long celebration of the 50th anniversary of the federal Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), a pioneer in the development of the drinking-water program in Minnesota shared his memories. Gary Englund’s career at the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) pre-dates the SDWA, and he served as the manager of the Section of Drinking Water Protection (which has had several different names) for more than 30 years.

Born in 1947, Englund was a multi-sport athlete at Gladstone High School on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He spent much of his time hunting and fishing at the family farm and developed a life-long love of the outdoors. “I was in the woods hunting and fishing when I was seven years old.”

Englund thought he would go into the army after high school but was directed by his dad to attend Michigan Tech University in Houghton. While he thought his outdoor interests might lead to a major in forestry, Dad once again stepped in and recommended engineering. As for the specific field, Englund picked civil engineering for no other reason than his best friend had chosen it.

Upon graduation, he was recruited by several state agencies in Minnesota, including the highway department, now the Minnesota Department of Transportation, but he was more interested in an environmental field and accepted an offer to work at MDH.

“I just liked being around water,” he explained. “I like to fish. I like to be around rivers. I like to be around streams. I just had a love for being around water. I love to fish. Originally, I wanted to work for DNR [Department of Natural Resources], but DNR didn’t have the kind of job for me. So the only job that I had available to me was I could either go to PCA [Pollution Control Agency] or I could go to the health department. And I went to the health department because I think I had more of an advantage there.”

As a staff engineer in a program with few staff at the time, Englund “did everything.” He wrote the codes for swimming pools, plumbing, wells, and just about anything else related to water. Fluoridation became an issue as the state required mandatory fluoridation of drinking water. He wasn’t involved in the politics of it but recalls the battle over the resistance by the city of Brainerd.

“We went to court with Brainerd, and Brainerd was going to have a situation where they were going to share the penalty with their board, and it was a misdemeanor, so it was 90 days in jail and a fine. And so they thought that they would take turns serving the 90 days in jail, and the judge said, ‘Wait a minute. A violation occurs every day.’ So every day they didn’t [fluoridate], it was 90 days in jail and a fine. So they finally decided they would start the fluoridation equipment. They put a tap on the outside of the building that didn’t have fluoride for people that didn’t want to put fluoride in their water, and hardly anybody ever used it.”

Englund performed plan review on the installation of fluoride systems. “We required a special kind of installation that had a break box, and you double pump. So if you siphon, if we’re going to siphon fluoride into the system, you’d only siphon a cup. That was a maximum you could siphon. You couldn’t siphon a whole 55-gallon drum or the whole 50 gallon barrel or whatever it was. We had a couple of incidents where we had some overfeeds. One was, I can’t remember where the heck it was. Can’t remember right now, but we only had one or two.

“Minnesota’s got over 50 years of history with fluoridation. And if you talk to the dentists, they were really happy because it really reduced the dental caries in children.”

Transition with Passage of SDWA

Prior to the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act, the drinking-water program ran on money from the state general fund as well as a fee program for plan review, which allowed them to hire a full-time person to perform this work. The SDWA eventually brought in federal money.

Englund became the section manager at this time and worked on achieving primacy, which allowed the state to take over the administration and enforcement of the SDWA from the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In essence, the Minnesota Department of Health became a subcontractor of the EPA, doing the federal agency’s work in Minnesota. “We were the first state in [EPA] Region Five to get primacy and probably the fifth state nationally,” said Englund, who credits Pauline Bouchard (who eventually became head of the Public Health Laboratory at MDH) of his staff for writing the grant to EPA. “We got it [primacy] because of her, because she could work full time on it. I didn’t have the time.”

Additional hires who became stalwarts were Bruce Olsen, who led source water protection initiatives; Gunilla Montgomery, who handled training necessary for water operators to become certified; Dick Clark and Doug Mandy, who oversaw the public water systems; and Dan Wilson, who managed the private-well program, which eventually became its own section.

However, the growth took time and relied on money available. “The first grant [from EPA] was only 10,000 dollars, so we didn’t have a lot of staff at that time. I only had one district engineer and a couple of sanitarians, and then I hired three more district engineers to do two districts, and then I hired a district engineer for every district, and then I created a hierarchy because you need to have a place for people to grow if they’re going to stay.”

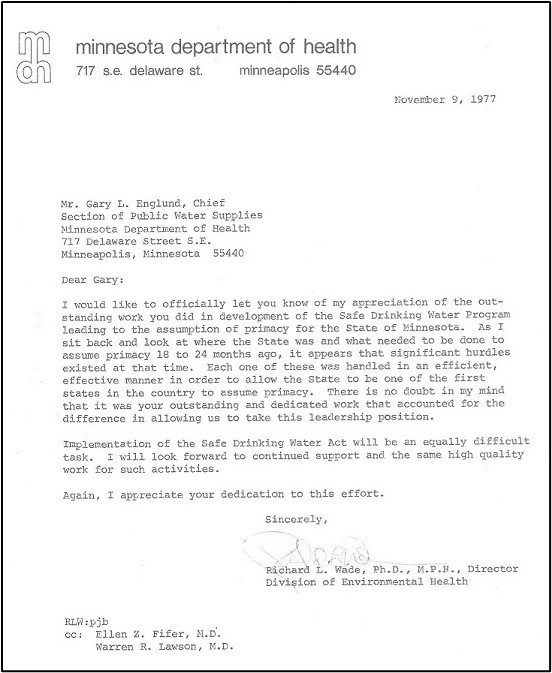

A letter to Gary Englund from division director Dick Wade after Minnesota achieved primacy in 1977.

The Englund Way

Long-timers credit this hierarchy and Englund’s philosophy on leadership with the strength of the program in the ensuing decades. “I always tried to hire somebody that was smarter than me because if they were smarter than me, it was easier for me to do my job,” he said.

Many past and current employees speak of how well Englund stood up for his people. After he retired, he has often heard, “We wish you were back. You fought for us.”

Englund is also remembered for being a financial whiz, and he was sometimes called on to help other sections in the MDH Environmental Health Division with their finances. “It was just something [finances] that I had an interest in, and I knew how to handle money. I knew how to take the dollars. The state fiscal year ran on a July to July. The federal fiscal year ran October to October, so I knew in that July to October quarter how to manage the money, so I didn’t have any state money left over. I didn’t have any federal money left over, but I also always knew how much money I had left in my budget every month. So I never overspent and I never underspent.”

Another important funding source began in the early 1990s with the inception of a new fee program, this one for $5.21 for each service connection in the state. (The fee was later raised to $6.36 and is now $9.72.) Cities collected the money from their customers and passed it on to the state, which has used it to pay for the analysis of water samples.

Englund explained the benefits of the state paying for analysis, coordinating the work with the MDH Public Health Lab, and dealing with the challenges of irregular sampling schedules for utilities and for specific contaminants.

“We had some monthly, we had some quarterly, we had some annually, we had some every three years, we had some every six years. . . . If they [the lab] got to a point where they were saturated and we gave ‘em another 10% of the samples, they would hire somebody else to do 10% of the samples, and they had 90% of the time where they weren’t doing anything. That was not efficient for me.

“Pauline [Bouchard] was running the lab at that time, and I said, ‘Pauline, I need to strike a deal with you. I will provide you – where you have staff that don’t have a complete year’s worth of sampling – I will provide them with enough samples to remain proficient.’ By doing that, that reduced my cost to our lab by 25%. That was significant.

“So then I took the additional samples that I had, and I subcontracted with private laboratories, and if the private laboratories went out to get samples done for lead and copper, they would’ve had to pay $40. That’s what the other states were paying their labs for doing lead and copper. I got that work for $10 a sample because number one, they knew how many samples they were going to get. They knew when they were going to come, and they knew they were going to get paid. So what I did by doing the sampling and monitoring program is I reduced the cost to the consumer of the state of Minnesota by driving the analytical costs down. Because if the utilities would’ve sampled, they would’ve had to pass that on to the customer.”

Early on, Englund decided to focus more on monitoring and less on enforcement. “Enforcement is not cheap. It was cheaper for me to monitor and create goodwill with the utilities than it was to create an enforcement program and create ill will.

“If there was a problem and they exceeded an MCL [maximum contaminant level] and they had to give public notice, that was an enforcement activity. We said, ‘You have to give public notice. You have to do this. You have to do that. You have to provide treatment, you have to do, and if you don't do it, we will have to take an enforcement action.’

“We didn’t have very many enforcement actions because we didn’t have very many violations.”

The approach of focusing more on cooperation and technical assistance instead of heavy-handed enforcement, along with fees that allow the state to pay for sampling, are major reasons that Minnesota has been a national leader in compliance with the SDWA, Englund said.

Connections

When Englund started, the Minnesota Department of Health was at 717 Delaware Street in southeast Minneapolis, on the edge of the University of Minnesota campus. The location, where MDH was until 2005, was because of the bond between the health department and university. Englund noted that the drinking-water program worked closely with some of the people at the U of M’s Department of Civil Engineering.

The relationship of drinking water and health is why the program in Minnesota is under a health rather than environmental agency. Englund noted this is rare around the country and that he was able to resist an attempt to move drinking water from the health department to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

Partnerships are another factor in the success of ensuring safe drinking water in the state. Minnesota Rural Water Association has circuit riders and trainers work with systems in Greater Minnesota, and, at Englund’s behest, MDH employees have become heavily involved in American Water Works Association (AWWA). Englund led the way, serving as chair as AWWA’s North Central (now Minnesota) Section and as the section’s director at the association level from 1990 to 1993.

Englund retired in 2003 (the picture below shows him receiving a plaque of appreciation from MDH). He splits his time between a home in Stillwater, near his son and daughter and their families, and the family farm in the Upper Peninsula. In either location, he spends a lot of his time in the woods and on the water.

“I’m 77 now,” Englund said. He still hasn’t slowed down.

Applications open for Water and Wastewater Operator Certification Advisory Council

The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) and Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) are inviting individuals to submit interest for participating on an advisory council to comment on the subject matter of possible rules related to water and wastewater operator certification.

The Advisory Council on Water Supply Systems and Wastewater Treatment Facilities shall advise the commissioners of MDH and MPCA regarding classification of water supply systems and wastewater treatment facilities, qualifications and competency evaluation of water supply system operators and wastewater treatment facility operators, and additional laws, rules, and procedures that may be desirable for regulating the operation of water supply systems and of wastewater treatment facilities.

The advisory council will consist of members from a range of interests related to the regulation of water and wastewater operator certification. The council will consist of the following categories of members:

- Certified Wastewater Treatment Facility Operator

- Certified Wastewater Treatment Facility Operator (outside the seven-county metropolitan area)

- Certified Water Supply System Operator

- Certified Water Supply System Operator (outside the seven-county metropolitan area)

- Certified Water Supply System Operator (nonmunicipal or noncommunity)

- Two Public Members (ideally one from an academic institution teaching water/wastewater operations)

- Member from an organization representing municipalities

The council will also have a representative from MDH and MPCA and a certified wastewater treatment operator from Metropolitan Council Environmental Services.

The advisory council will meet quarterly at a centralized location. Applications are due September 30 with appointments made by the end of the year.

Apply: Office of the Minnesota Secretary of State - Boards & Commissions

Search for Advisory Council on Water Supply Systems and Wastewater Treatment Facilities.

Go to > top

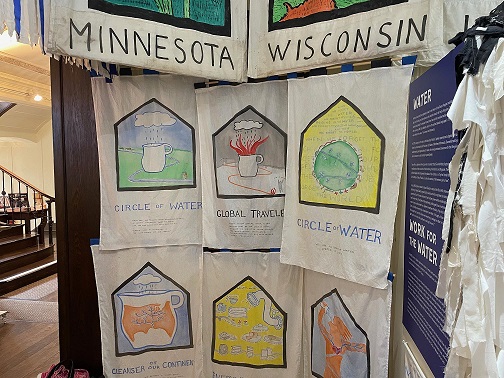

Hennepin History Museum celebrates 1983 Circle of Water Circus tour

Alyssa Thiede and Sandy Spieler in front of the puppets in the Circle of Water exhibit at the Hennepin History Museum.

The Hennepin History Museum has opened an exhibit, Circle of Water: Puppetry as an Agent of Change, that will run through June 2026. The exhibit celebrates the four-month Circle of Water Circus in 1983, which was created by the In the Heart of the Beast (HOBT) Puppet and Mask Theatre of Minneapolis.

HOBT was founded in 1973 as the Powderhorn Puppet Theatre and operated out of the basement of the Walker Community Church in south Minneapolis. In 1979 the theatre changed its name to “In the Heart of the Beast Puppet and Mask Theatre,” moving into the Gustavus Adolphus building on Lake Street and finally into the nearby Avalon Theatre in 1988. Once a family-oriented movie house, the Avalon eventually switched to adult movies. When HOBT moved into the Avalon, it marked the transition on its marquee with “Bye Bye Porn, Hello Puppets.”

Circle of Water Circus

By this time HOBT was focusing on water issues. It put on a variety of shows, including a trip down the Mississippi River, which was a long-time ambition of one of the theater’s founders, Sandy Spieler. Stopping in river cities of all sizes, the troupe of 25 adults, 5 children, and 2 dogs put on a Big Ring Show, side shows, and half- and full-day artist residencies depending on the length of their stay. The main attraction was a performance featuring 150 puppets and original music that “explored the devastation of colonialism throughout the history of the region with an optimistic look towards the future,” according to the museum.

“We tried to be in the town as long as they could host us, and we tried to do workshops with the local people to really consider their connection to the river because a big thing that we were trying to do is just get the people to turn their faces to the water again, which had become a sewage line,” recalled Spieler. “The more that we could be with the local people, the better.”

The tour did its Big Ring Show in 21 cities, and the troupe performed before audiences of several hundred to 4,000, the latter during a two-week stay in St. Louis with performances beneath the Gateway Arch in St. Louis and artist residencies in a number of neighborhoods. “Coming into St. Louis, they brought us in on a tugboat so that they could do a media event,” said Spieler. “They liked it [the circus] so much we were able to do not just one residency, but there were probably five different residencies.

“Our team was split up in different neighborhoods, and then they liked it so much as a community organizing thing that where people could then come together for an event that they continued for a couple years afterwards.”

Banners were made for each of the states along the river route.

While a tugboat was used as part of a media event in St. Louis, most of the group traveled by bus, although some came via a small houseboat. “We called it the Collapso [a play on Jacque Cousteau’s Calypso] because it just kept breaking down,” Spieler said. “And that was the same summer that Jacques Cousteau’s men were on the Mississippi River. We kept intersecting with them in different places. And there they were with their big fancy boat, and there we were with our little houseboat. We enjoyed meeting them. They were, of course, intriguing French men. “

The troupe stayed in churches, mansions, college dormitories, and camp sites. Kevin Kling, who became a noted storyteller and commentator on National Public Radio, was a member of the troupe with the artistic skills to make some of the puppets. “He’s actually a pretty fine sculptor,” noted Spieler.

As for funding of the tour, “It wasn’t,” said Spieler. “No one could envision what we were talking about. It’s the problem the puppet theater has always had. It’s not pure visual art. It’s not pure theater. It’s a wild mix of art and theater and ecological education and advocacy.”

The Exhibit

Hennepin History Museum curator Alyssa Thiede said they first accepted a donation of some of HOBT’s puppets during a time when it was uncertain whether the theater was going to be staying at the Avalon. “That’s when Sandy and then-board chair Laura Wilhelm were trying to find a home. Back in 2021 is when they came to us. Have you heard of Sandy’s Puppet Nest?” The “nest” is Spieler’s garage and an adjacent structure she built as a means of saving the puppets.

The donation led to the exhibit about the circus that, noted by the museum, “fostered community, and raised awareness of the ecological distress of the river through the ancient tradition of puppetry.”

Water Initiatives at Hennepin History Museum

The Circle of Water exhibit is just one of the water initiatives the museum is engaged in. “The unceasing rains and floods of June have put water at the forefront of everyone’s attention,” says a museum press release. “Under the watchful eye of our beloved Water Mask [another gift from HOBT, which was made for one of its Mayday Festivals, pictured at right], recently installed in a place of honor in our Great Stairwell, our efforts to reach out to others and tell different stories has organically coalesced around the importance of water.”

Executive director John Crippen explained some of the museum’s current activities, including the Great Swamp/Skunk Hollow Walking Tours, coordinated in partnership with the St. Louis Park Historical Society. The tour series highlights the often-complicated relationship between people and nature and how decisions made in one era have consequences for succeeding generations. A related exhibit about the tours is now on display at the St. Louis Park Library and may be installed at other locations in St. Louis Park in the months ahead.

Another is the Ĥaĥá Wakapádaŋ/Bassett Creek Oral History Project, which recently won a Minnesota History award. Started as an oral-history project by Valley Community Church in Golden Valley, the project encompasses the lived experiences of indigenous people in the Twin Cities suburbs. “Everyone knows about Native Americans on reservations and urban areas,” said Crippen. “This focuses on Indians in suburbia and the native approach of water quality. Native Americans view water as a relative, asking ‘How are we living in harmony of our relatives?’”

Crippen said it wasn’t their primary intention to dwell on water, but a “nice confluence of events” made it happen,” describing it as “a piece of serendipity that they came together at the same time.”

In 2009, the Minnesota Department of Health and Minnesota Section of American Water Works Association commissioned HOBT to make a water mural that wraps around a bottle filling station in the EcoExperience Building at the Minnesota State Fair. The mural is still on display.

Past Waterline Articles

Minneapolis Theatre Focuses on Water in Series of Performances

Public Art St. Paul Promotes Water Awareness

Go to > top

New factsheet on lead in schools

The Minnesota Department of Health has a new factsheet available that public water systems can use to let schools and child cares know about recently updated lead testing requirements and resources to help them test and remediate lead in schools and other educational settings, including child-care facilities.

Legislation passed in 2017 requires Minnesota public school districts and charter schools to test for lead in water. The web page has a link to a model plan and a toolkit, which provides resources for schools to communicate about results of testing for lead and water.

In addition, the factsheet has information about WIIN (Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation) grants and flyers that can be downloaded.

Reducing Lead in School Drinking Water

Go to top

DWP doings

In the process of learning our acronyms, about all Brady Krueger knows is that he is the new CPWSU DE for Fergus Falls. (That’s Community Public Water Supply Unit District Engineer to the rest of us, Brady.) Brady grew up in Fergus Falls and, with his family, recently returned to the area after living in the Twin Cities for 18 years. He was an air permit engineer for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency from 2014 to 2022 and then worked for American Engineering Testing on air permits and compliance. He’s now on his third state agency as he had worked many years for DHS (that’s Department of Human Services, although Brady may have already nailed that one) in group homes serving people with developmental disabilities before he went to school for engineering.

Brady and his wife of 18 years, Rebecca, and children Van, Martie, and Forest are all in love with their dog, Moose.

Brady says, “When I’m not working or chasing kids, my favorite thing in the world is drumming. I’ve played in several rock bands over the years, dating all the way back to when I was 13 and drumming in a punk band with older high school kids. The whole rock star thing didn’t pan out, so here I am having to work for a living.”

The Krueger clan (other than Moose)

Haripriya Naidu has joined the CPWS Unit as a lead and copper compliance coordinator. Haripriya is from Andra Pradesh, India, and, before coming to MDH, worked as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Illinois, Urbana, and at a private company in Minneapolis. In her free time, she likes to be outdoors, to explore local parks, and to experiment in the kitchen and try to develop new recipes, which, she admits, may not always be tasty.

Haripriya has a husband, Karthik, and a three-year-old daughter, Chandravarna. Although they are petless, Haripriya once fostered an American pit bull terrier, Alpine.

Karthik, Haripriya, and Chandravarna

Recovering journalist Rebecca Toews (she/her) is now a communications and strategic initiatives coordinator for Drinking Water Protection (DWP). Growing up in the driftless bluff country of southeastern Minnesota, she started her career in television news in Rochester, Minnesota, and Madison, Wisconsin, Rebecca got her master’s degree in Eugene, Oregon, where she directed the student newsroom and wrote her thesis on roller derby. She moved back to Minnesota to be closer to family and tranisitioned into nonprofit and public-sector communications. Rebecca has a special interest in community storytelling around public-sector and human-interest stories.

She has a partner, Shawn, and six-year-old child, Ruby Luna, who has a dog-brother (Townes) and a cat-sister (Gorjira).

Rebecca enjoys road trips, cross-country skiing, kickboxing, and finding the next summer festival.

Rebecca, Shawn, Ruby Luna, Gorjira, and Townes (not necessarily in that order)

Jackie Becker has joined the Minnesota Department of Health as a compliance officer and data coordinator, working with community water systems on the Lead and Copper Rule.

From New York, she completed her undergraduate education in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (home of the grave of James Buchanan), and then worked on aquatic species for the Montana Conservation Corps in Missoula before returning to school to get her master’s degree in public health.

Jackie recently moved to St. Paul with her partner, Zack, and their two dogs, Bowdin and Oakley. She loves everything outdoors from running and hiking to fishing.

Bowdin, Jackie, Oakley, and Zack

Peyton Carroll and Hannah Neighbor are the new district engineers in Mankato, north and south districts, respectively.

Peyton attended Michigan State and enjoys reading, golfing, and cooking. Hannah—out of the University of Minnesota—enjoys going on walks with her husband, visiting coffee shops, going to thrift stores, and baking sourdough.

Go to top

More honors for Moorhead

Moorhead won the Great Minnesota State Fair Tap Water Taste Test, held on the Sustainability Stage of the EcoExperience building at the State Fair August 22. Richfield was the runner-up while Belle Plaine finished third and New York Mills fourth. Past champions of the taste test are Golden Valley, International Falls, Minneapolis, Fairmont, St. Cloud, Lake Elmo, Chaska, Crookston, St. Paul, and Saint Peter. The Minnesota Section of American Water Works Association (AWWA) has conducted the taste test at the fair since 2012.

Go to top

More from CISA on security

By Aaron Morningstar, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

Every day, water and wastewater treatment facilities across the country use a variety of techniques and an array of chemicals to purify water so that it is safe to use and drink. When used properly, these chemicals greatly benefit our society. However, some of the chemicals are dangerous and can be an attractive target for terrorists or criminals.

Through the years, water and wastewater facilities have been the target of nefarious incidents—from cyberattacks manipulating the amount of chemicals being released into the water to the theft of cylinders filled with dangerous chemicals.

Could your facility be next? Enhance the security of dangerous chemicals at your facility and protect your community’s critical water supply by reaching out to CISA’s voluntary security program. CISA offers programs to water and wastewater treatment facilities nationwide and offers no-cost services and tools to help identify the risk associated with your on-site chemicals.

Our trained security advisors are located around the country and can help you understand the risks associated with your region, your on-site chemical holdings, and your facility’s existing security measures. Because no two facilities are the same, CISA is available to help improve your security posture in a way that is tailored to your facility and your business model. From on-site assessments and assistance and security training, to cyber and physical security exercises and cybersecurity resources tailored for water and wastewater facilities, CISA has a variety of services and tools that can help your water and wastewater treatment facility enhance both your cyber and physical security.

Another training resource is the Power of Hello strategy for employee vigilance.

Contact CISA with questions, CISARegion5@cisa.dhs.gov.

Go to top

Golden Spike for Lewis & Clark

Using the symbol and concept of a Golden Spike for the transcontinental railway in 1869, the Lewis & Clark Rural Water System (LCRWS) put a gold wrap around a 12-inch diameter pipe as it was installed outside Sibley, Iowa, on July 26, marking the final section of pipe placed for the entire project.

LCRWS executive director Troy Larson said the service area encompasses 337 miles of pipe. Larson noted that more remains to be done, but the completion of the distribution system marked a significant milestone in the decades-long mission to divert water from the Missouri River to parts of South Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota.

Conceived in 1988 as a way of serving water-challenged areas in these states, the Lewis & Clark project takes water from a series of wells that tap into an aquifer adjacent to the Missouri River near Vermillion, South Dakota.

The water first reached Minnesota in 2015, reaching Rock County Rural Water District. Three years later the final partner in the state, Worthington, was connected.

Much remains to be done, according to Larson, including a third and final phase of the treatment plant.

More information on Lewis & Clark:

Lewis and Clark Regional Water System Nearly Complete in Minnesota

The first section of pipe, laid June 14, 2004 southwest of Vermillion, South Dakota, near the Missouri River.

Go to top

Another Drinking Water Institute in the books

As part of the 2024 Drinking Water Institute, teachers took a field trip to watch the replacement of a lead service line on St. Paul’s East Side.

The annual Drinking Water Institute for Educators was held in July at St. Paul Regional Water Services. The Minnesota Department of Health and Minnesota Section of American Water Works Association have been conducting these institutes since 2001. Starting in 2025, the Minnesota Water Well Association will also be a sponsor.

Science teachers from around the state come together and develop action plans to create inquiry-based activities that they can integrate into their existing science curriculum.

The 2024 Institute was the last to be moderated by Lee Schmitt of the Hamline University Center for Global Environmental Education. David Grack will succeed him as moderator starting next year.

The 2025 Drinking Water Institute will be August 4-6 in Eden Prairie. More information:

Lee Schmitt (the one wearing the nametag that says Lee) accepts an award for his decades of service to the Drinking Water Institute.

Quote of the Quarter

Sincerity is the key to success. Once you can fake that, you’ve got it made.

—Groucho Marx

Reminder to all water operators

When submitting water samples for analyses, remember to do the following:

- Take coliform samples on the distribution system, not at the wells or entry points.

- Write the Date Collected, Time Collected, and Collector’s Name on the lab form.

- Attach the label to each bottle (do not attach labels to the lab form).

- Include laboratory request forms with submitted samples.

- Do not use a rollerball or gel pen (the ink may run).

- Consult your monitoring plan(s) prior to collecting required compliance samples.

Notify your Minnesota Department of Health district engineer of any changes to your systems.

Go to top

Calendar

Operator training sponsored by the Minnesota Department of Health and Minnesota AWWA will be held in the coming months.

Register for schools and pay on-line:

Go to top