Drinking Water Protection

- Drinking Water Protection Home

- About Us

- A-Z Index of Contaminants in Water

- Community Public Water Supply

- Drinking Water Grants and Loans

- Drinking Water Institute

- Drinking Water in Schools and Child Cares

- Drinking Water Revolving Fund

- Laws and Rules

- Noncommunity Public Water Supply

- Source Water Protection

- Water Operator and Certification Training

- Drinking Water Protection Contacts

Related Topics

- Annual Reports

- Drinking Water Risk Communication Toolkit

- Drinking Water Protection External Resources

- Fact Sheets

- Forms

- Invisible Heroes Videos: Minnesota's Drinking Water Providers

- Noncom Notes Newsletter

- Sample Collection Procedures (videos, pictures, written instructions)

- Waterline Newsletter

Related Sites

- 10 States Standards

- Clean Water Fund

- Health Risk Assessment – Guidance Values and Standards for Water

- Minnesota Well Index

- Water and Health

- Wells and Borings

Environmental Health Division

Waterline: Summer 2025

Editor:

Stew Thornley

Staff:

Noel Hansen, Erin Culver, Bob Smude, David "Hollywood" Rindal, Rebecca Toews

Get email updates to The Waterline newsletter by signing up below. An e-mail notice is sent out each quarter when a new edition is posted to the web site.

On this page:

- Decommissioned water towers not forgotten

- New to MDH Drinking Water Protection Section: Olivia Ebbers

- Governor Walz proclaims Safe Drinking Water Week in Minnesota

- A Minnesota city's move toward chlorination appears to have stopped a recent Legionnaires' Disease outbreak

- Reminder to all water operators

- Calendar

Decommissioned water towers not forgotten

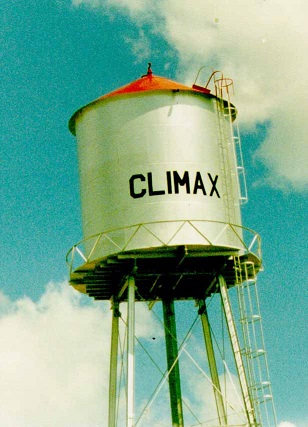

As of March 2025, 658 Minnesota community water systems (632 municipalities) have an elevated water tower with a total of 969 towers in the state. However, the ones not in use became the fascination of KARE-TV reporter Audrey Russo, who did a story on towers that no longer hold water but that have been embraced by townspeople, many of whom rally against efforts to tear them down. Shown above are examples of such towers, including Elk River, which was restored to its original colors of silver with a red top. The Milaca tower has been out of service for nearly 20 years but is still structurally sound and remains on the property of the old city hall, which is now the city museum. “Nobody wanted to see it go,” public works supervisor Gary Kirkeby said of the community reaction and desire to save it.

Russo also visited a still-in-service tower in Shakopee and interviewed water distribution supervisor Dave Hagen, who said the 1940 tower is the oldest single-pedestal, welded tower in the country. The tower was considered enough of an engineering marvel that it was featured in the December 1946 Popular Mechanics, which described it as “an unusual water tower shaped like a giant mushroom that rises 130 feet into the air. The shining ball atop the steel shaft is 43 feet in diameter.”

The KARE-11 story aired May 27, 2025, and can be found at 'They hold memories': Behind the push to preserve Minnesota's historic water towers.

Too Dear to Demolish: Historic Minnesota Water Towers

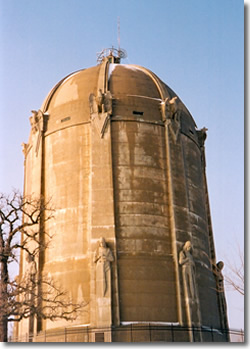

Minneapolis has three towers designated as city landmarks. The Kenwood tower, to the west of downtown, was built in 1910. The Prospect Park tower, off University Avenue in southeast Minneapolis, was built in 1913, and, two years later, the city purchased an existing water tower, the Washburn tower in an area known as Tangletown off 50th Street and Nicollet Avenue in south Minneapolis, and extended its height by 25 feet for additional pressure. The city increased the pressure even more in 1931 by demolishing the Washburn tower and building a new one. None is used for water storage anymore (the Washburn tower lasted the longest in its original function, holding water into the 2000s). Each tower is distinct. Prospect Park residents use the “witch’s hat” feature of their tower as a means to decorate the tower on Halloween. The Washburn tower has a number of adornments, including 16-foot-tall “guardians of health” mounted on pilasters, along with eagles at the base of the dome.

In 2013, as the water tower in downtown Osseo was approaching its 100th birthday, no longer containing water but serving as a familiar landmark, the city included an item in its newsletter, asking residents for feedback as it considered demolishing the tower.

Kathleen Gette, a proposal writer in her career, volunteered to write the grants to seek historic status for the tower, which would open doors for funding and help cover the costs to rehabilitate the iconic tower. Gette also started a “Save the Osseo Water Tower” Facebook group and collaborated with the Minnesota Historical Society’s State Historic Preservation Office. The efforts were successful. On June 5, 2017, the tower was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The familiar Ear of Corn water tower in Rochester received special status as the city’s Historic Preservation Commission voted unanimously in December 2023 to designate the tower as a historic structure. The Rochester city council approved the designation the following month.

The tower is 151 feet high and was built in 1931 by Reid, Murdoch and Company to supply its canning plant. The plant, last operated by Seneca Foods, has been demolished, but the tower lives on and is now owned by Olmsted County. A member of the preservation commission called it, “Rochester’s Eiffel Tower of Corn.”

Pipestone (left) and Brainerd (right) are concrete towers designed by the same architect, L. P. Wolff, around 1920. Pipestone’s 132-foot-high tower held water until 1976, when it was replaced by a larger new one. Brainerd’s tower, 141 feet high, was decommissioned in 1958 and has survived more than one threat to have it dismantled because the price of rehabilitation was considerably more than the cost of razing it.

However, both towers live on and are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Kasson and Ogilvie have water towers more than 100 years old.

Kasson’s 86-foot-high tower was built in 1895 and originally had a 2,000-gallon wooden tank, which was replaced with a metal tank a year later. The distinguishing feature is the base of limestone, which came from a quarry three miles north of Kasson.

The poured-in-place concrete cylinder in Ogilvie, built in 1918, is 80 feet high. The structure is topped by a parapet to make it resemble a medieval fortified tower. Ogilvie, then a village, was able to organize its first volunteer fire department with the tower providing the infrastructure to improve its water system. The tower held water until 2011.

St. Paul’s Highland 127-foot-high tower (on the left) held water until 2017, and the pump room in its basement is still in use. Completed in 1928, the tower was designed by Clarence Wigington, who was the first Black municipal architect in the country. Wigington worked for the city from 1915 to 1949 and designed a number of significant structures, including the Como Park Pavilion. The eight-sided tower rises on the second-highest of seven hills in St. Paul and has an observation deck that is open to visitors twice a year. On the right is a reinforced concrete tower built in 1924 on College Hill next to St. Mary’s Hospital in Rochester. Both towers are on the National Register of Historic Places.

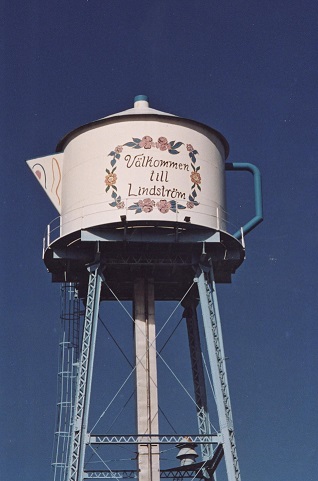

Lindstrom saved its water tower after a new one was built in 1992, converting the old one to a coffee pot with the addition of a handle, spout, and knob. Initially, steam came out of the spout but was discontinued. However, the steam is returning in the summer of 2025, with a fog machine inside the tower emitting simulated steam twice a day.

One That Got Away

For years the Iron Range city of Eveleth labeled its towers not as Old and New, but rather as Hot and Cold, causing both residents and visitors to often ask if the temperatures varied in the two towers (it didn’t). Eventually the Old/Hot tower was dismantled with the Cold label removed from the existing one.

Of interest

Go to > top

New to MDH Drinking Water Protection Section: Olivia Ebbers

Olivia Ebbers is a lead and copper compliance officer in the Drinking Water Protection Section Community Water Systems unit. From Worthington, Minnesota, she got her bachelor’s degree in medical laboratory science at Winona State and moved to the Twin Cities to work at M Health Fairview for a year. She returned to school, at St. Mary’s University, where she got her master’s in business administration and worked as an environmental lab associate at St. Croix Sensory before coming to MDH in February 2025.

Fun facts about Olivia: “I enjoy traveling and have been to 29 states as well as Canada and Norway. I also enjoying reading, being active outdoors (biking, swimming, hiking, etc.), and attending sporting events.”

Go to top

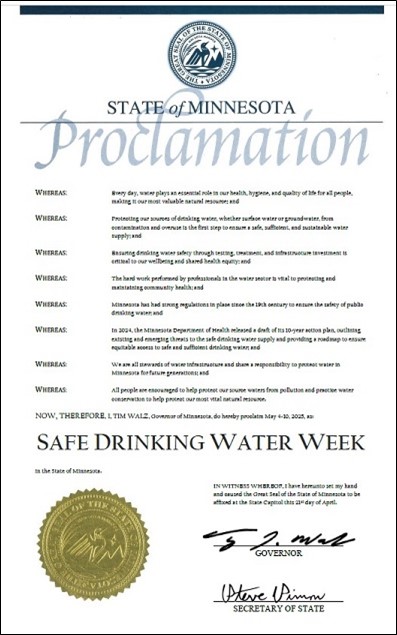

Governor Walz proclaims Safe Drinking Water Week in Minnesota

Safe Drinking Water Week in Minnesota was celebrated in May and included a proclamation from Governor Tim Walz.

Go to top

A Minnesota city's move toward chlorination appears to have stopped a recent Legionnaires' Disease outbreak

By Rebecca Toews

The Northeast Water Operators School included a tour of the Grand Rapids water treatment plant to observe what the city has done to combat Legionella.

Beginning in April 2023, MDH and Grand Rapids Public Utilities (GRPU) investigators began tracking an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease. Over the course of the next year, the system saw one or two positive cases at a time, while trying to determine the source of the outbreak. All-told, approximately 30 people required hospitalization for their illness, and two people died because of their illnesses.

Legionnaires’ Disease is one of two legionellosis diseases caused by Legionella bacteria, which causes a dangerous and potentially fatal lung infection. People can contract the disease if they breathe in small water droplets that contain Legionella bacteria. It is most commonly seen in places that create water mist, such as hot tubs, showers, decorative fountains, and cooling towers that are not properly maintained.

Grand Rapids Public Utilities began chlorinating their water system in June 2024. They have had no positive results for the disease since July 2024. The outbreak underscores the importance of disinfecting water at community water systems and working with the community to prioritize public health.

“Getting the data is important,” says Mac Graupman, a consultant that helped GRPU establish its protocols for stopping the outbreak, but implementing solutions will only be effective if you have customer buy-in. GRPU had success in their monitoring play because they had established trust in their community.”

About disinfection in Minnesota water systems

Considered by many to be one of the most significant health developments in modern history, chlorination is one of the most common types of drinking water disinfection. It kills bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms that cause disease and immediate illness.

Continuous disinfection is required for surface water systems (where lakes and rivers are the source of drinking water), treatment processes that expose the water to outside or open air, and systems that use certain types of corrosion control. Just 61 municipal community water systems, out of almost 1,000, do not currently chlorinate—and only 10 of those systems have populations above 10,000 residents.

“Disinfection is a critical tool in determining the quality of water,” says Kim Larsen, MDH Community Public Water Supply supervisor. “It is the most effective means to control opportunistic pathogens in the distribution system.”

Beyond protecting against Legionella bacteria, chlorination has other benefits. Chlorine residuals allow the distribution system operators to gauge water age and identify emerging issues in the system.

Despite its many benefits, there are some concerns with chlorination. When chlorine reacts with certain organic materials in the water, disinfection byproducts (DBPs) can form. These DBPs can have negative health effects; some research indicates that certain byproducts of water disinfection can be linked to liver, kidney, and reproductive effects as well as central nervous system problems. Any system that chlorinates is required to regularly test its treated water to determine if it has any regulated disinfection byproducts present.

Maintaining water quality in buildings and homes

Another concern with chlorination is maintaining the chlorine residual at a consistent level. Even in systems that chlorinate, water quality problems can arise when water sits in a building’s plumbing system. Sediment can build up in pipes, and bacteria can grow on softeners, filters, plumbing fixtures, and hot water heaters that have not been in use regularly or properly maintained. “We needed to help residents to see that there is a shared responsibility for maintaining water quality,” says Steve Mattson, Water/Wastewater Department manager with GRPU. “We can get the water to your house and have it be clean, but you have to be responsible for your flushing plan, especially in buildings and apartments. Everyone has a role in stopping the spread of this disease.”

That’s why it’s important for homeowners and apartment or building operators to take actions to ensure water stays safe within their homes and buildings:

- Keep it clean. Clean and maintain devices such as faucets, showerheads, and water heaters per the manufacturers’ recommendation to limit sediment, scale, corrosion, and biofilm.

- Keep it cold. Cold water should be kept cold throughout a building’s plumbing. Below 68 degrees Fahrenheit is best.

- Keep it hot. Hot water should be kept hot throughout a building’s plumbing. Determining appropriate hot water temperatures will depend on the plumbing, fixtures, and facility type (such as a nursing home). If the building does not currently have thermostatic mixing valves at showers and faucets, install them to store and circulate water at the recommended temperatures.

- Keep it moving. Moving water will help maintain appropriate temperatures and avoid stagnation, which can allow Legionella to grow. Keeping water moving in the building will also help pull disinfected water from the community water supply into your building. Legionella grows best between 77 and 113 degrees Fahrenheit. Avoid these temperatures by keeping cold water cold, by storing hot water hot, by managing water temperature at point-of-use, and by keeping water moving.

MDH actively communicates the benefits of chlorination and adds the recommendation to sanitary survey inspection reports to install chlorination. Systems that do chlorinate must be set up to maintain a consistent residual by implementing a monitoring and action plan.

Tips for community water systems using chlorination:

- Work with your district engineer to develop an effective and proactive residual monitoring plan.

- Collect samples on a regular schedule from similar locations that represent the entire distribution system.

- Use a dedicated form to record and save data to observe fluctuations that may indicate issues needing action.

Drinking water treatment operations must meet competing objectives. They must provide adequate protection from bacteria, viruses, and microorganisms, while reducing levels of DBPs to meet U. S. Environmental Protection Agency standards. It is not an easy task and requires close and continuous attention.

Learn more:

- Legionnaires’ Disease Outbreak in Grand Rapids, 2023-2024 - Minnesota Department of Health

- Drinking Water Chlorination: Frequently Asked Questions - Minnesota Department of Health

- Disinfection and Disinfection Byproducts - Minnesota Department of Health

- Safe Drinking Water in Your Home - Minnesota Department of Health

- Maintaining Water Quality in Buildings and Homes - Minnesota Department of Health

Go to top

Reminder to all water operators

When submitting water samples for analyses, remember to do the following:

- Take coliform samples on the distribution system, not at the wells or entry points.

- Write the Date Collected, Time Collected, and Collector’s Name on the lab form.

- Attach the label to each bottle (do not attach labels to the lab form).

- Include laboratory request forms with submitted samples.

- Do not use a rollerball or gel pen (the ink may run).

- Consult your monitoring plan(s) prior to collecting required compliance samples.

Notify your Minnesota Department of Health district engineer of any changes to your systems.

Go to top

Calendar

Operator training sponsored by the Minnesota Department of Health and Minnesota AWWA will be held in the coming months.

Register for schools and pay on-line:

Go to top