Mental Health Promotion

Mental health is more than the absence of disease. Everyone has a state of mental health, and this can change across the lifespan. Not having a mental illness, does not guarantee good mental health. Similarly, having a mental illness, does not guarantee poor mental health. It includes life satisfaction, self-acceptance, sense of purpose, identity, feeling connected and belonging, empowerment, and resilience, which is the ability to bounce back after set-backs.

The World Health Organization defines mental health as:

"A state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community."

Most people think about mental illness when they hear "mental health". For clarification, many use the term "mental well-being" or "flourishing" instead.

Mental Health and Well-Being Narrative

Minnesota Public Health Mental Well-Being Advisory Group

September 2016

These are public health core values and beliefs regarding mental health and well-being. This narrative is intended to help guide community investments in mental health promotion and illness prevention work.

Everyone deserves opportunity for Mental Health and Well-Being.

Brains are built through experience. The interaction between our biology and experiences shapes the chemicals and structures of our brains, particularly during early childhood and adolescence.

Fear, trauma, and chronic stress negatively impacts Mental Health and Well-Being. While we all experience stress and hard times, the cumulative impact of chronic or intense stress is real. It gets built into our bodies and is passed on to the next generation.

Where we live, learn, work, and play impacts our Mental Health and Well-Being. This includes structures and environments that are safe, nurturing, inviting, toxin free, and facilitate relationships, community and culture.

Resilience is not enough in the face of oppression. Oppression is bad for our Mental Health and Well-Being. Intentional systemic changes to end oppression are essential to help individuals, families and communities thrive.

Physical health & Mental Health and Well-Being are intertwined. When we experience physical illness, injury or pain it has a negative impact on our Mental Health and Well-Being. Improving our physical health can improve our Mental Health and Well-Being.

Everyone and every system has a role and responsibility in ensuring our collective Mental Health and Well-Being. We all benefit when public and private organizations work together.

Mental Health and Well-Being happens in and through community. We can spread and protect Mental Health and Well-Being by building positive relationships, social connections and drawing on community and cultural assets.

Mental Health and Well-Being requires a sense of purpose and power. To truly experience Mental Health and Well-Being we need to feel that we have the power to shape our world and change our lives and conditions for the better. For many, historical trauma is a reality that takes away our sense of purpose and power and continues to be part of our lived experience and reality.

Positive relationships are central to Mental Health and Well-Being. Relationships provide meaning and facilitate skill development and feelings of belonging. Lack of positive relationships and isolation are detrimental. Positive relationships are not automatic; families and communities need information, resources, and other supports to help cultivate and sustain them.

Culture shapes our definitions and understanding of Mental Health and Well-Being. It is OK and healthy for individuals and communities to have different perspectives on what it means to be well and how to achieve well-being. Culture is a source of healing, connection and strength.

Everyone needs opportunity to learn and practice skills to manage life and engage in the world. Skills to manage stress, find balance and focus, and engage socially, are critical components that should be cultivated throughout the lifespan in both formal and informal settings. Skills and experiences that help people feel valuable and engage in their family, community and economy are also critical.

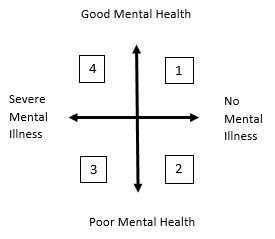

Is mental wellbeing and illness really distinct?

Research supports a distinction between mental illness and mental well-being. Life experiences, a weak relationship between symptoms of mental illness and mental well-being, and distinct patterns of health outcomes indicate that mental health is more than the opposite of mental illness. For example, individuals with poor mental well-being and no mental illness (quadrant 2) are one and a half times more likely to have arthritis compared those with mental well-being and mental illness (quadrant 4), those with poor mental health and mental illness are two times more likely. Circumstances can unmask or fuel poor mental health. The person who has been repeatedly laid off, a parent of a child with a special health care need, an LGBTQ youth without a role model or support, a new retiree with a changing role may, be experiencing particularly poor mental health. Without the right environment, resources and supports, problems can persist and grow.

Quadrant descriptions:

- Flourishing - Good mental health and no mental illness

- Languishing - Poor mental health, no mental illness (e.g. socially isolated, feel disempowered, no sense of purpose, unemployment, high stressors- poor housing, poverty)

- Mental illnesses and poor mental health

- Recovery - Mental illness- symptoms of mental illness are managed. Also experiencing good mental health (e.g. strong support system, life satisfaction and purpose, a home, employment, sense of empowerment, and positive identity).

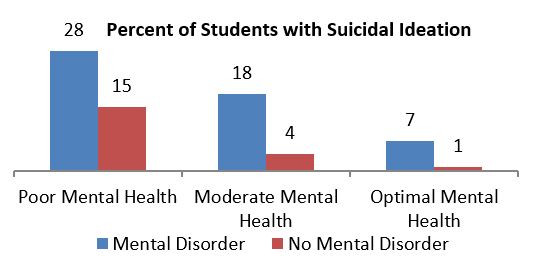

Mental Wellbeing Matters

Poor mental health is a risk factor for mental illness. Mental disorders are the most common cause of disability in the U.S. contributing 18.7% of all years lost to illness, disability, or premature death (DALYs). Poor mental health may precede or exacerbate mental illness. People with poor mental health, but no current mental illness are three to six times more likely to develop mental illness in the next ten years. Improving mental health decreases the likelihood of developing mental illness in the next ten years. Poor mental health, with or without the presence of mental illness, is a risk factor for: chronic disease (cardiovascular, arthritis), increased health care utilization, missed days of work, suicide ideation and attempts, death, smoking drug and alcohol abuse, physical inactivity, injury, delinquency, and crime. Health improves incrementally as mental health improves. For example, college students with and without a current mental disorder, are more likely to report suicide ideation when experiencing poor mental health.

The burden of poor mental health on the health of the population is significant given the health implications and the population impacted. The population with poor mental health and no current mental illness includes over half of U.S. adolescents, young adults and adults, a much larger group than the population with a mental disorder. An estimated 20% of the U.S. adult population has optimal mental health. A study that measured the mental health among U.S. adolescents age 12-18 found that less than 40% of youth have optimal mental health, including 37% of students who did not meet criteria for depression, and 2% of those with depression.

*Resources available upon request.

Measuring Mental Wellbeing

There are multiple operational definitions of mental well-being. Keyes’ Mental Health Short Form tool currently has substantial empirical evidence across cultures to support validity and utility. The tool defines 3 mental health criteria including: emotional, psychological and social well-being, feeling, functioning and social functioning. An estimated 17-32% of the U.S. adult population ages 25-75 are flourishing. Most have moderate mental health (57%) and many are languishing (12%). Individuals with mental illness can flourish, but it’s less common; 1% of the total population and 7% of those with mental illness are flourishing.

| Major Depression | Flourishing | Moderate Mental Health | Languishing | TOTAL |

| NO | (17%) | (57%) | (12%) | (86%) |

| YES | (1%) | (9%) | (5%) | (14%) |

| TOTAL | (18%) | (65%) | (17%) | (100%) |

|

FLOURISHING CRITERIA: high level on 1 of the 2 emotional, and 6 of 11 remaining scales of functioning.

|

*Resources available upon request.

A Public Health Framework for Action

- People - the social-cultural environment,

- Place - healthy environment, including the built environment and

- Equity - the economic/educational environment.

The arenas of opportunity for communities and a practical examples include:

| PEOPLE | |

| Supportive relationships and social connectedness | Mentoring, Parent Supports, Community Engagement |

| Social, emotional and life skills | Social emotional learning, Self-care skills, Life skills, Job training, Positive psychology skills/practices (e.g. Gratitude - 3 things) |

| Community, culture, and faith | Cultural identity and learning, Social clubs |

| Healthy lifestyle | Exercise, Sleep and Nutrition |

| Trauma and healing | Healing practices, Historical trauma dialogue, Trauma-informed systems |

| PLACE | |

| Healthy environment | Quality housing, Access to nature, Community look and feel |

| EQUITY | |

| Economic opportunities and supports | Living wage, Food support, Paid family leave, Quality child care |

| Equitable social policies | Preventing discrimination and support inclusion, Incarceration, School suspension, Zoning for culture/religious practices |

All of these operate in the context of community.

Community CapacityThe key aspect of a public health approach to mental health is community leadership. According to the WHO, community is the most important setting and community empowerment, ownership and control of their destiny is the most important strategy for mental health promotion. Community capacity, the ability in a given community to solve collective problems and improve community well-being, is linked to decreased rates of mental illness, antisocial behavior, neighborhood violence, homicide, and suicide. Youth in communities with greater social capital, develop trust and reciprocity earlier, a developmental process that is important for building relationship and resilience. Community capacity mitigates health consequences of social isolation; isolated individuals do better in communities with greater capacity. The foundational health equity practices describe capacity building work, and includes expanding: community understanding about what shapes mental health, community capacity to create change (e.g. leadership development), and focus on policy as key drivers.

What does mental health promotion look like in your community?

Here are a few examples:

- Programs that help young people develop problem-solving and coping skills, either in school or in community-based organizations, such as peer leadership activities, suicide prevention curricula, and life skills curricula.

- Mentoring programs and activities that help a young person connect with a caring adult.

- Home visiting programs in which nurses or other professionals work directly with families to support parents, provide education about child development and promote parent-child interaction.

- Any activities that promote exercise, sleep, and good nutrition.

- Projects that encourage help-seeking and reduce the stigma associated with mental illness.

- Initiatives that encourage gratitude and mindfulness.

- Creating spaces for communities to gather, build relationships and identify common needs.

- Community dialogues about historical trauma.

- Working on changing policies to reduce incarceration, substance abuse, or other adverse childhood experiences.