Commercial Tobacco Use

- Commercial Tobacco Use Home

- Data and Reports

- Get Help Quitting

- Prevention and Treatment

- Tobacco and Your Health

Learn More

- Behavioral Health and Commercial Tobacco

- E-cigarettes and Vaping

- Flavored Commercial Tobacco

- Menthol Commercial Tobacco

- Nicotine and Nicotine Dependence

- Nicotine Pouches and Other Emerging Products

- Promoting Quitting and Treatment

- Secondhand Smoke and Aerosol

- Smoke-Free Housing

- Traditional and Sacred Tobacco

Related Topics

Contact Info

Menthol-Flavored Tobacco Products

Menthol is a flavor additive commonly used in cigarettes and other tobacco products. Federal law currently prohibits the manufacture and sale of flavored cigarettes, with the exception of menthol.1

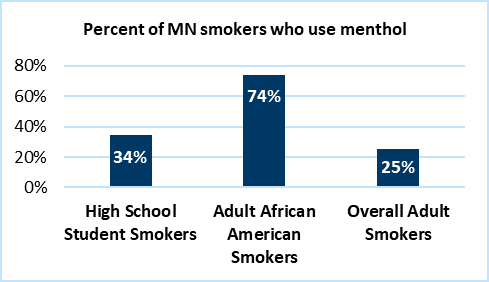

Menthol cigarette use is high among youth and African Americans.

One in three Minnesota high school smokers use menthol;2 overall 25 percent of adult smokers use menthol.3

From 2004 to 2014, as the use of non-menthol cigarettes by youth and young adults declined, the use of menthol cigarettes among these groups increased or remained constant.4 This disparate progress in reducing youth smoking rates is likely perpetuated by the sale and marketing of menthol cigarettes.5

Additionally, almost one in four Minnesota African Americans are current smokers (compared to 14.4 percent of adults statewide), with the vast majority using menthol.6 While menthol use is high in many communities, use by African Americans is particularly concerning as they are 30-36 percent more likely to die of lung cancer than non-Latino whites;7 they are also 53 percent more likely to die of heart disease.8

Additionally, almost one in four Minnesota African Americans are current smokers (compared to 14.4 percent of adults statewide), with the vast majority using menthol.6 While menthol use is high in many communities, use by African Americans is particularly concerning as they are 30-36 percent more likely to die of lung cancer than non-Latino whites;7 they are also 53 percent more likely to die of heart disease.8

Menthol tobacco products are a serious public health threat.

Menthol makes smoking easier and more attractive for youth.

Menthol makes experimentation easier because it can mask irritation from smoking. It has a minty taste and smell and produces cooling and numbing sensations that reduce the harshness of cigarette smoke.9-16 This may encourage youth to keep smoking when they would otherwise stop.9

Menthol makes experimentation easier because it can mask irritation from smoking. It has a minty taste and smell and produces cooling and numbing sensations that reduce the harshness of cigarette smoke.9-16 This may encourage youth to keep smoking when they would otherwise stop.9

The use of characterizing flavors began in the 1970s to make it easier for new smokers to start, and to become regular smokers more easily.17-19

Menthol intensifies addiction, especially for young smokers.

Youth who smoke menthol cigarettes are more dependent on cigarettes and show stronger addiction to nicotine than those who smoke non-menthol cigarettes.9, 10, 15, 20-22 Additionally, youth who start smoking with menthol cigarettes are more likely to transition to regular smoking than those who start with non-menthol cigarettes.9, 22

Menthol makes it harder for smokers to quit for good.

A large number of studies show that menthol users have a higher nicotine dependence and smoking urge.14 Thus, menthol users have a harder time quitting than non-menthol users.23, 24 This finding is stronger among African American and other minority populations than among white smokers,25-27 despite African American menthol users expressing greater confidence in their ability to quit than non-menthol users.28

A large number of studies show that menthol users have a higher nicotine dependence and smoking urge.14 Thus, menthol users have a harder time quitting than non-menthol users.23, 24 This finding is stronger among African American and other minority populations than among white smokers,25-27 despite African American menthol users expressing greater confidence in their ability to quit than non-menthol users.28

Women who smoke menthol cigarettes before a pregnancy are also more likely to start smoking again after the pregnancy than those who smoke non-menthol cigarettes.29

Industry marketing practices target specific populations.

Menthol cigarette marketing practices are targeted more toward younger people and African Americans than older adults and other racial or ethnic groups.9, 10, 30-32 Menthol cigarette marketing has consistently targeted minority and low-income communities.33-36 This strategy results in higher smoking rates among these groups.9, 10, 37

Advertising is a strong driver of brand preference, especially among youth, and it is likely that price discounts, promotions, product placement, and geographic location have been used to drive menthol cigarette preference among youth and young adults as well as the African American community.9, 10

Communities are addressing menthol tobacco use.

The African American Leadership Forum – in partnership with Hennepin County Public Health, Bloomington Public Health, Minneapolis Health Department and St. Paul-Ramsey County Public Health – recently surveyed residents to learn about menthol tobacco use in local communities.

It was conducted as part of the Menthol Cigarette Intervention Grant, required by the Minnesota Legislature, to deepen understanding of African American use patterns and perceptions and attitudes toward menthol tobacco, and it will serve as a basis for community engagement and education moving forward.

Survey results reinforce the need to educate and raise awareness on the harms of menthol tobacco use, and they also show that a majority of African American community members support new laws to reduce tobacco’s harm.

Learn more about the 2015 Menthol Cigarette Intervention Grant.

Proven tobacco control policies and evidenced-based strategies are necessary to prevent all forms of tobacco use, including flavored tobacco products.38 Effective strategies include price increases as well as restricting youth access to tobacco products and exposure to tobacco product marketing.39 The Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration states that "removal of menthol cigarettes from the marketplace would benefit public health in the United States."9

Download this information: Menthol-Flavored Tobacco Products (PDF)

Learn More

- Flavored Commercial Tobacco Products

- 2015 Menthol Cigarette Intervention Grant

- Case Study: Community-led Action to Reduce Menthol Cigarette Use in the African American Community (PDF)

- Infographic: Menthol Tobacco: A Pervasive Threat in Minnesota’s African American Community (PDF)

- Menthol Toolkit (Public Health Law Center)

- Documentary: 'Black Lives / Black Lungs' shows how menthol tobacco ended up in black communities

- Tobacco NUMBRS - Tobacco and Nicotine Use in Minnesota: Briefs, Reports, and Statistics

References

- Federal Trade Commission, Cigarette Report for 2012. 2015, Federal Trade Commission: Washington, DC.

- Health, M.D.o., Teens and Tobacco in Minnesota: Highlights from the 2017 Minnesota Youth Tobacco Survey. 2018.

- Minnesota, C. and M.D.o. Health, Tobacco Use in Minnesota: 2014. 2014.

- United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General., The health consequences of smoking--50 years of progress : a report of the surgeon general. 2014, Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General. 2 volumes.

- Giovino, G.A., et al., Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: is menthol slowing progress? Tobacco control, 2013: p. tobaccocontrol-2013-051159.

- Minnesota, C. and M.D.o. Health, Tobacco Use in Minnesota: 2014. 2015(Unpublished Data).

- Society, A.C., Cancer Facts & Figures 2010. 2010.

- Kayani, N., S. Homan, and S. Yun, Racial disparities in smoking-attributable mortality and years of potential life lost-Missouri, 2003-2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2010. 59(46): p. 1518-1522.

- TPSAC, Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations. 2011, Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee, Center for Tobacco Products, Food and Drug Administration: Washington, DC.

- FDA, Preliminary Scientific Evaluation of the Possible Public Health Effects of Menthol versus Nonmenthol Cigarettes. 2013, Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD.

- Kuhn, F.J., C. Kuhn, and A. Luckhoff, Inhibition of TRPM8 by icilin distinct from desensitization induced by menthol and menthol derivatives. J Biol Chem, 2009. 284(7): p. 4102-11.

- Henningfield, J.E., et al., Does menthol enhance the addictiveness of cigarettes? An agenda for research. Nicotine Tob Res, 2003. 5(1): p. 9-11.

- Giovino, G.A., et al., Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use. Nicotine Tob Res, 2004. 6 Suppl 1: p. S67-81.

- Ahijevych, K. and B.E. Garrett, The role of menthol in cigarettes as a reinforcer of smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res, 2010. 12 Suppl 2: p. S110-6.

- Hersey, J.C., J.M. Nonnemaker, and G. Homsi, Menthol cigarettes contribute to the appeal and addiction potential of smoking for youth. Nicotine Tob Res, 2010. 12 Suppl 2: p. S136-46.

- Klausner, K., Menthol cigarettes and smoking initiation: a tobacco industry perspective. Tob Control, 2011. 20 Suppl 2: p. ii12-9.

- R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. Conference report #23, June 5, 1974 Bates No. 500254578-4580 1974; Available from: https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=jfcb0102

- Kreslake, J.M., et al., Tobacco industry control of menthol in cigarettes and targeting of adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health, 2008. 98(9): p. 1685-92.

- Kreslake, J.M., G.F. Wayne, and G.N. Connolly, The menthol smoker: tobacco industry research on consumer sensory perception of menthol cigarettes and its role in smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res, 2008. 10(4): p. 705-15.

- Hersey, J.C., et al., Are menthol cigarettes a starter product for youth? Nicotine Tob Res, 2006. 8(3): p. 403-13.

- Collins, C.C. and E.T. Moolchan, Shorter time to first cigarette of the day in menthol adolescent cigarette smokers. Addict Behav, 2006. 31(8): p. 1460-4.

- Nonnemaker, J., et al., Initiation with menthol cigarettes and youth smoking uptake. Addiction, 2013. 108(1): p. 171-8.

- Delnevo, C.D., et al., Smoking-cessation prevalence among U.S. smokers of menthol versus non-menthol cigarettes. Am J Prev Med, 2011. 41(4): p. 357-65.

- Rojewski, A.M., B.A. Toll, and S.S. O'Malley, Menthol cigarette use predicts treatment outcomes of weight-concerned smokers. Nicotine Tob Res, 2014. 16(1): p. 115-9.

- Levy, D.T., et al., Quit attempts and quit rates among menthol and nonmenthol smokers in the United States. Am J Public Health, 2011. 101(7): p. 1241-7.

- Gundersen, D.A., C.D. Delnevo, and O. Wackowski, Exploring the relationship between race/ethnicity, menthol smoking, and cessation, in a nationally representative sample of adults. Prev Med, 2009. 49(6): p. 553-7.

- Okuyemi, K.S., et al., Relationship between menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among African American light smokers. Addiction, 2007. 102(12): p. 1979-86.

- Reitzel, L.R., et al., Associations of menthol use with motivation and confidence to quit smoking. Am J Health Behav, 2013. 37(5): p. 629-34.

- Reitzel, L.R., et al., Race/ethnicity moderates the effect of prepartum menthol cigarette use on postpartum smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res, 2011. 13(12): p. 1305-10.

- Anderson, S.J., Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation behaviour: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control, 2011. 20 Suppl 2: p. ii49-56.

- Yerger, V.B., J. Przewoznik, and R.E. Malone, Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved, 2007. 18(4 Suppl): p. 10-38.

- Cruz, T.B., L.T. Wright, and G. Crawford, The menthol marketing mix: targeted promotions for focus communities in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res, 2010. 12 Suppl 2: p. S147-53.

- Hyland, A., et al., Tobacco outlet density and demographics in Erie County, New York. Am J Public Health, 2003. 93(7): p. 1075-6.

- Yu, D., et al., Tobacco outlet density and demographics: analysing the relationships with a spatial regression approach. Public Health, 2010. 124(7): p. 412-6.

- Schneider, J.E., et al., Tobacco outlet density and demographics at the tract level of analysis in Iowa: implications for environmentally based prevention initiatives. Prev Sci, 2005. 6(4): p. 319-25.

- Novak, S.P., et al., Retail tobacco outlet density and youth cigarette smoking: a propensity-modeling approach. Am J Public Health, 2006. 96(4): p. 670-6.

- Dauphinee, A.L., et al., Racial differences in cigarette brand recognition and impact on youth smoking. BMC Public Health, 2013. 13: p. 170.

- Neff, L.J., et al., Frequency of tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2015. 64(38): p. 1061-1065.

- Control, C.f.D. and Prevention, Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs, in Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs. 2014, CDC.