Traditional Practices and Cultural Norms

OB-GYN Care for Afghans: A Toolkit for Clinicians

On this page:

Traditional practices

Cultural norms regarding women's health issues

References

- There are many traditional practices that Afghans may follow during pregnancy. These traditions vary among the diverse Afghan population and may be disrupted or altered with changes in family systems and culture in the U.S.

- Black antimony, or surma, may be applied to the baby’s eyes, eyebrows, and/or umbilical cord. Surma may contain lead, so it is recommended to educate the family about the risks and suggest safe alternatives.1

- In general, children are highly desired in Afghanistan, and women may feel pressure to have as many children as possible. This, coupled with fear of side effects, may lead to reluctance towards using contraception or spacing pregnancies.

- Intrauterine devices (IUDs), injectable contraceptives, oral contraception, implants, and condoms may be available to women in Afghanistan, especially if they are married, educated, affluent, and/or reside in urban areas. Others may use natural family planning such as the rhythm, lactational amenorrhea, or withdrawal methods. Some husbands and/or families disapprove of contraception use, so some women use contraception discreetly without informing family members.2,3

- Abortions have historically been allowed in Afghanistan if the mother’s life is at risk.4

Traditional practices

There are many traditional practices that Afghans may follow during pregnancy. These traditions vary among the diverse Afghan population and may be disrupted or altered with changes in family systems and culture in the U.S. Providing quality care for Afghan patients includes being open-minded, respectful, and as accommodating as possible to traditional practices that patients and their families may wish to incorporate into the pregnancy, labor, and postpartum periods. Remain mindful that some practices may lead to poor clinical outcomes and consider how to respectfully educate patients about potential harm to the mother or baby and safe alternatives (such as using eyeliner makeup instead of surma, which may contain lead).1 Reference the lead toxicity screening section on General Health Care Recommendations for more information.

During pregnancy

It is common for Afghan women to first reveal news of their pregnancy to their mothers-in-law or mothers rather than telling their husbands directly, with the expectation that they will spread the word. Dietary changes for pregnant and postpartum women are also common. Generally, women eat the same food as their families. However, pregnancy is considered to be a “hot” condition for which “cold” foods (vegetables, fruits, fish, dairy products) are recommended, and “hot” foods (cereal products, cinnamon, ginger) are avoided. Foods such as apples and pomegranates are believed to increase a child’s beauty, while yogurt and cold water are believed to result in big eyes.3

During labor

When labor is near, mothers’ hands may be placed in a bowl of flour and the flour given as alms. Only laboring women and midwives are typically in the delivery room, although there may be exceptions for female relatives or husbands with patients’ permission. Afghan women are encouraged to drink water steeped with an herb (Panje BeBe). They may also drink holy water or read verses from the Quran. Some families will also give mothers chicken soup or hot milk to ease delivery.3

Newborn and postpartum care

Within the first one to three days after birth, babies are bathed and the Azan, or Islamic call to prayer, is recited to them. An amulet with holes may be attached to the swaddling cloth. Black antimony, or surma, may be applied to babies’ eyes and eyebrows. Ash and/or surma may also be applied to umbilical cords two to three days after babies are born. In an effort to comfort babies and prevent an umbilical hernia, families may wrap a coin placed over the umbilical cord with a scarf. Mothers may follow a specific bathing schedule and be secluded for about forty days to rest and sleep. During the seclusion period, men are not allowed to visit, but mothers can visit healthcare providers. Prior to beginning breastfeeding, a gold or silver ring may be touched to babies’ mouths for good fortune. A large leaf may be placed on mothers’ breasts to help produce milk.3

Cultural norms regarding women’s health issues

In general, children are highly desired in Afghanistan, and women may feel pressure to have as many children as possible. This may lead to reluctance towards using contraception or spacing pregnancies. Family planning, pregnancy, and birth practices vary between rural and urban areas. For example, families in rural areas tend to be less informed about recommended medical practices due to lack of access to healthcare and education. Family structure also tends to be more paternalistic, with husbands or their families acting as primary decision-makers. Families in urban areas tend to have greater access to education and healthcare, and women's in-laws tend to be less involved in decisions regarding their care.

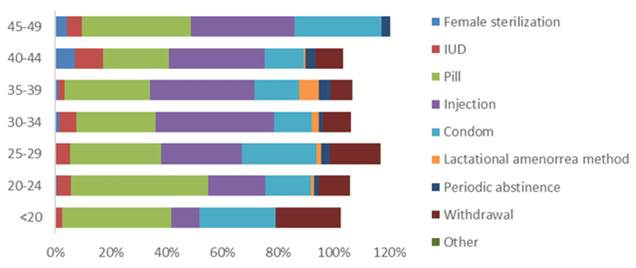

In Afghanistan, many women do not have access to education about the menstrual cycle and how to use family planning methods. However, intrauterine devices (IUDs), injectable contraceptives, oral contraception, implants, and condoms may be available to them, especially if they are married, educated, affluent, and/or reside in urban areas. Others may use natural family planning such as the rhythm, lactational amenorrhea, or withdrawal methods (Figure 3). Women may be hesitant to use contraception due to possible side effects including excessive fatigue, irregular periods, or spotting. Some husbands and/or families disapprove of contraception use, so some women use contraception discreetly without informing family members.2,3

Figure 3: Percentage of ever-married women 12-49 years of age with a live birth in 2 years preceding survey (excluding currently pregnant) using contraceptives, by age. Contraceptive use among Afghan women in the 2018 Afghanistan Health Survey increases with age, education, and higher wealth quintile2

Most Afghan women are aware of the practice of abortion. However, abortions in Afghanistan have historically only been allowed if the mother’s life is at risk.4 Vaginal delivery is preferred, in part because women are discouraged from becoming pregnant after three C-sections.

References

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2022, February 28). Kohl, Kajal, Al-Kahal, Surma, Tiro, Tozali, or Kwalli. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-products/kohl-kajal-al-kahal-surma-tiro-tozali-or-kwalli-any-name-beware-lead-poisoning

- Afghanistan Health Survey 2018. (2019). KIT Royal Tropical Institute. https://www.kit.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/AHS-2018-report-FINAL-15-4-2019.pdf

- Afghan Arrivals: Pre- and post-natal care. (2022, October 12). Minnesota Department of Health. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aQKXoBcSbaM&feature=youtu.be

- Country Profile: Afghanistan. (2017, May 7). Global Abortion Policies Database; World Health Organization and Human Reproduction Programme. https://abortion-policies.srhr.org/country/afghanistan/